The World Health Organization estimates that antibiotic resistant infections kill more than a million people worldwide every year, so many researchers are actively looking for new ways to combat it.

Rachel Ee (right), a pharmaceutical scientist at the National University of Singapore, designs antimicrobial peptides to combat antibiotic resistance. In a recent study led by her graduate student Wei Meng Chen (left), Ee’s team showed that they could control the bacteria-killing ability of net-forming peptides by making small changes to the peptide’s sequences.

Rachel Ee and Wei Meng Chen

Pharmaceutical scientist Rachel Ee at the National University of Singapore has a unique strategy up her sleeve. Instead of using drugs, Ee and her team design short peptides that can self-weave into microscopic nets that trap and kill bacteria. Ee’s team previously showed that these peptides could assemble themselves into nets in the presence of bacteria, likely because they recognized molecules on bacterial cell membranes.1-3

In a recent study, Ee and her team demonstrated how slight tweaks to the design of these peptides could alter their ability to trap and kill bacteria.4 Their work, published in Small, may provide a new set of tools to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

“It’s an interesting study that gets at the rules of what kinds of [peptide] sequences and parameters regulate the trapping and killing bacteria,” said Shuichi Takayama, a biomedical engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology who was not involved in the study. “Antibiotic resistance is not going to go away anytime soon, so anything that can be added to the arsenal, I think, is helpful.”

Ee’s team engineers short, hairpin-like antimicrobial peptides containing 10 to 15 amino acids that kill bacteria by boring holes into their membranes. In a 2021 study, the researchers designed 10 such peptides, aiming to investigate differences in their ability to kill bacteria. These peptides typically exist as discrete coils, but the researchers observed that one peptide unexpectedly formed a net-like structure, which they called nanonet.

“We thought it was a mistake,” Ee said.

At first, Ee thought that the unexpected structure had come from the bacteria, but when she cultured bacteria alone or in the presence of the other nine peptides, no nanonet formed. This confirmed that the peptide, not bacteria, formed these structures.

Conversely, the researchers found that the peptide only formed nanonets in the presence of bacteria—specifically, responding to lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acid, negatively charged molecules that make up the membranes of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively. The fact that the peptide’s self-weaving property depends on the presence of bacteria, or at least their components, indicates its potential as an antimicrobial agent.

Ee’s team previously found that they could turn a non-nanonet-forming peptide into one that can form nanonets by introducing three amino acids—leucine, threonine, and alanine—at the turn of the hairpin. In the present study, the researchers wanted to know if peptide sequence could also influence nanonet architecture, for instance, how tightly the structures wrap around bacteria.

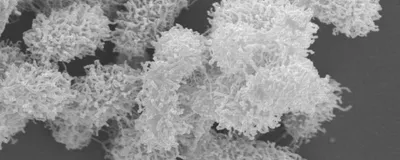

They discovered that peptides with more bulky, aromatic residues like phenylalanine and tryptophan produced tight nanonets. Electron microscopy data revealed that the nanonet formed by one of these peptides even managed to individually encase each single bacterium, like a carefully wrapped present, before killing them. On the other hand, peptides with more negatively charged residues like glutamic acid formed loose nanonets that captured multiple bacteria at once but failed to kill them.

“We still don’t know whether one type is better than the other, but now we have the capability to design nets of different morphologies for different applications,” Ee said. “There’s a whole playbook of amino acids and chemical modifications we can make to a peptide structure, so we can mix and match, like Lego bricks.”

Ee said that researchers in the field typically develop antimicrobial peptides to treat topical infections. This is what Ee has in mind too, since “there are still many infections on the [body’s] surface that we have not effectively managed.” But people may be able to take nanonet-forming peptides orally in the future, once researchers tackle their potential stability and toxicity issues. “The peptides are shorter, so they have a higher chance of going systemic with oral administration,” Takayama said. “But you still have to do something to make it orally available.”

Takayama thought that using the peptides alongside antibiotics is likely a more immediate application, and it turns out that progress in this area is already underway. Ee’s team recently discovered that bacteria that were once trapped in nanonets can undergo genetic changes that lower their overall fitness, even after they were freed. Since less fit bacteria are likely more susceptible to killing by antibiotics, this suggests that nanonets may help overcome resistance by working with drugs that already exist. Ee shared that this work is currently being reviewed for publication.

Ee’s team is also trying to design even shorter nanonet-forming peptides. “Shorter means cheaper, and cheaper is good for translation into the clinic,” Ee said. “I think that’s very important.”

- Tram NDT, et al. Manipulating turn residues on de novo designed β-hairpin peptides for selectivity against drug-resistant bacteria. Acta Biomater. 2021;135:214-224.

- Tram NDT, et al. Bacteria-responsive self-assembly of antimicrobial peptide nanonets for trap-and-kill of antibiotic-resistant strains. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(5):2210858.

- Tram NDT, et al. Multifunctional antibacterial nanonets attenuate inflammatory responses through selective trapping of endotoxins and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(20):2203232.

- Chen WM, et al. Controlling nanonet morphology via residue-specific modulation of β-hairpin peptide for enhanced bacterial trapping. Small. 2025;21(35):e2505823.