A drawing based on one of Ramón y Cajal’s “selfies,” with his pyramidal neuron illustrations around him. According to Hunter, Ramón y Cajal obsessively took photos of himself throughout his life. DAWN HUNTER, WITH PERMISSIONIt was in the spring of 2015 when Dawn Hunter saw Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s century-old elaborate drawings of the nervous system in person for the first time, at the late scientist’s exhibit within the National Institutes of Health. She was instantly compelled to recreate his ornate illustrations herself.

A drawing based on one of Ramón y Cajal’s “selfies,” with his pyramidal neuron illustrations around him. According to Hunter, Ramón y Cajal obsessively took photos of himself throughout his life. DAWN HUNTER, WITH PERMISSIONIt was in the spring of 2015 when Dawn Hunter saw Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s century-old elaborate drawings of the nervous system in person for the first time, at the late scientist’s exhibit within the National Institutes of Health. She was instantly compelled to recreate his ornate illustrations herself.

“I just immediately started drawing [them] because they were so beautiful,” says Hunter, a visual art and design professor at the University of South Carolina. “His drawings in person were even more amazing than I thought they were going to be.”

Ramón y Cajal’s drawings first caught Hunter’s eye while doing research for a neuroanatomy textbook she was asked to illustrate in 2012. Ramón y Cajal, hailed by many as the father of modern neuroscience, depicted the inner workings of the brain through thousands of intricate illustrations before his death in 1934. He first posited that unique, inter-connected entities called neurons were the central nervous system’s fundamental unit of function.

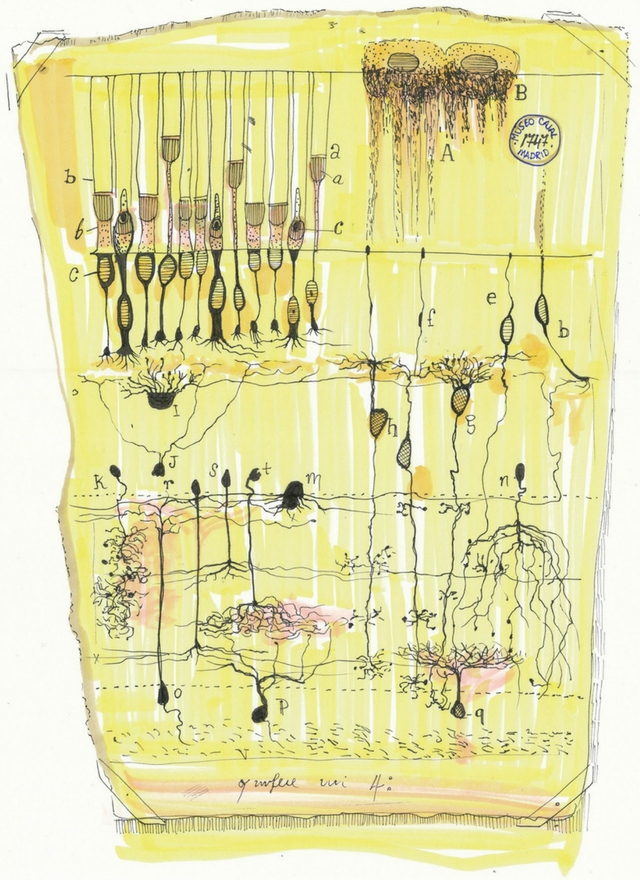

A recreation of Ramón y Cajal Cajal’s retina depiction. “His retina drawing is particularly interesting because he combines both of his main drawing techniques. . . . Part of the drawing is designed and drawn out preliminarily and part of it is drawn from observation,” says Hunter.DAWN HUNTER, WITH PERMISSIONWhile recreating his work, Hunter was able to shed unprecedented light on how he went about his craft. “Some neuroscientists erroneously think that he traced all of his drawings from a projection, which he did not,” she says. This involves expanding a magnified image of the specimen being viewed under the microscope onto the table using a drawing tube or camera lucida. While he did use this tool in certain instances, she says, he drew some of his drawings, like his famous pyramidal neurons, “through his observation with his eye,” a technique known as perceptual drawing.

A recreation of Ramón y Cajal Cajal’s retina depiction. “His retina drawing is particularly interesting because he combines both of his main drawing techniques. . . . Part of the drawing is designed and drawn out preliminarily and part of it is drawn from observation,” says Hunter.DAWN HUNTER, WITH PERMISSIONWhile recreating his work, Hunter was able to shed unprecedented light on how he went about his craft. “Some neuroscientists erroneously think that he traced all of his drawings from a projection, which he did not,” she says. This involves expanding a magnified image of the specimen being viewed under the microscope onto the table using a drawing tube or camera lucida. While he did use this tool in certain instances, she says, he drew some of his drawings, like his famous pyramidal neurons, “through his observation with his eye,” a technique known as perceptual drawing.