Paleontology typically conjures images of digging up dusty bones in the field. So why is paleontologist Thomas Clements watching fish rot in the laboratory? “People are always a bit surprised when I tell them what I do for a living,” Clements says. It might seem odd, he explains, but by better understanding the process of decay, he hopes to answer big questions about how living things become fossils in the first place.

Clements specializes in taphonomy, a subfield within paleontology that deals with the process of fossilization. He’s especially interested in why some soft tissues, such as muscles and certain internal organs, are more likely to show up in the fossil record than others. It’s important that paleontologists get to the bottom of this mystery, he says, as only by understanding the processes of decay and preservation will they be able to correctly interpret that record. “If you’re looking at a fossil from 500 million years ago, it can be hard to know what tissues are absent because of decay and what tissues are absent because they were not evolutionarily present,” says Clements, currently a research fellow at the University of Birmingham in the UK.

Only a very small percentage of anything that was ever alive becomes fossilized. While it’s typically the hard parts—bones, teeth, and shells—that get replaced by minerals and preserved, soft tissues also stand a chance in certain circumstances, says Orla Bath Enright, a paleontologist at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. “These soft and squishy parts are much rarer in the fossil record because their preservation requires a particular set of environmental conditions,” she says, including low oxygen levels, availability of minerals, and rapid burial.

It absolutely is disgusting work, but you get used to it. It helps to have a strong stomach, though.

—Thomas Clements, the University of Birmingham

Around the world, there are a small number of sites, known in the research literature as Konservat-Lagerstätten, where the conditions were just right. The mineral that yields the most exceptional fossils, and is most frequently observed at these sites, is calcium phosphate (also known as apatite). When soft tissues are replaced by this mineral—a process known as phosphatization—organic structures can be preserved with subcellular fidelity. Under a microscope, even individual muscle fibers and cell organelles may be visible.

Muscles, stomachs, and intestines are more commonly captured by calcium phosphate than are the liver, gonads, and kidneys, says Clements. Some researchers think this is because different organs decay at different rates, creating distinct pH microenvironments around themselves. In this scenario, the pH of some organs falls below the critical threshold of 6.4, allowing fossilization to occur there but not elsewhere. An alternative hypothesis is that it’s not the way organs rot, but the tissue biochemistry specific to each organ that determines its likelihood of becoming a fossil.

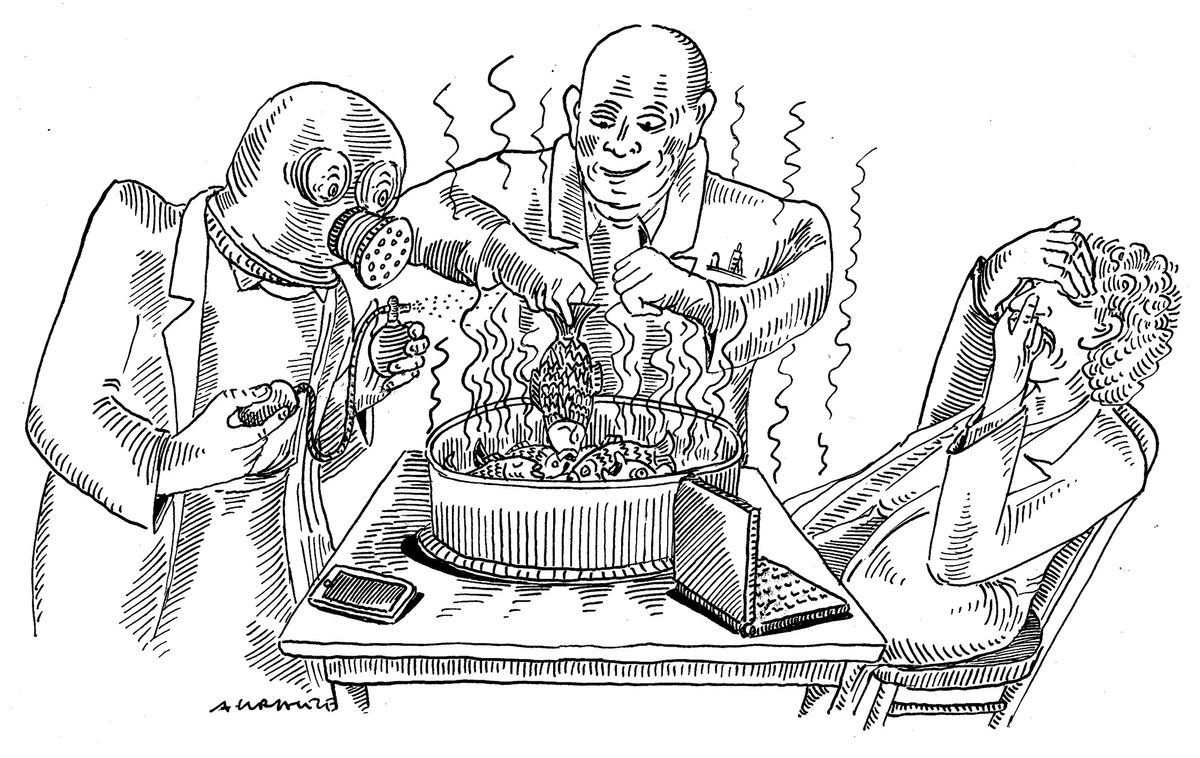

It was through trying to directly test these hypotheses several years ago that Clements found himself, as a doctoral student at the University of Leicester, monitoring how sea bass carcasses rot over the course of 70 days. Previously, researchers were limited by equipment that could only monitor pH fluctuations around a decaying carcass, not inside it, he says. Technological improvements have since resulted in smaller, more powerful pH probes able to collect data automatically and internally. With fellow paleontologists Sarah Gabbott and Mark Purnell, Clements placed probes inside specific organs to document real-time pH gradients during the early stages of decay. “We were just fortunate that we could secure equipment that was robust enough to sit inside a rotting fish for 70-odd days multiple times a year,” he says.

After inserting the probes, the team suspended each fish carcass in plastic mesh netting in a frame, placed the contraption in a container filled with artificial sea water, and left the carcass to rot. The result was just as revolting as you’d imagine, says Clements. “The smell is horrific and there’s bits of rotten fish everywhere,” he says. “It absolutely is disgusting work, but you get used to it. It helps to have a strong stomach, though.”

Somewhat surprisingly, the results revealed that organs do not generate unique pH microenvironments during decay (Palaeontology, 65:e12617, 2022). Clements says the inside of the fish became soup-like rather quickly, with most internal organs becoming “unrecognizable” within just five days. This soup of decaying organs had a pervasive pH environment—below the phosphatization threshold—that persisted until the skin finally ruptured. “There was this long-standing idea that pH of the microenvironment is important in soft tissue preservation,” says Philip Wilby, who is paleontology lead at the British Geological Survey and was not involved in this study. “This experiment clearly puts that idea to bed and shows that pH microenvironment is not the important process here.”

Clements and his colleagues instead conclude that, when conditions are amenable, it is tissue biochemistry that contributes to selective preservation. Tissues such as muscles, for example, are already rich in phosphates—which help kick-start phosphatization—as well as collagen fibers that can act as a substrate for the process to occur. Stomach and intestinal contents often also contain high levels of phosphates.

Wilby says these findings are an important step forward, but questions remain. “Phosphatization requires particular conditions that we are still working to understand. It is not a simple process,” he says. “If it was, everything that ever died would be phosphatized.” Wilby points out that because these experiments used recently dead fish from a fishmonger, the researchers may have missed important decay processes that occur in the first few hours after death. There are also other potential factors that bear further investigation, such as the chemistry of the sediments in which fossils typically form.

Bath Enright, who also was not involved in this study, agrees there is more to learn and says she is excited about how the technological advances used by Clements and colleagues are pushing the field of experimental taphonomy forward. “Decay is a process that occurs over a period of time until the carcass is gone,” she says. “This paper shows the necessity of tracking decay at the level of specific organs to understand what is happening internally in a carcass, because that’s where a lot of the action is happening.”