Immune checkpoint blockade therapy relies on releasing a natural brake in the immune system to fight cancer. This therapy activates the body’s CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, which mount an attack against tumors. However, scientists did not fully understand what facilitates tumor killing by T cells.

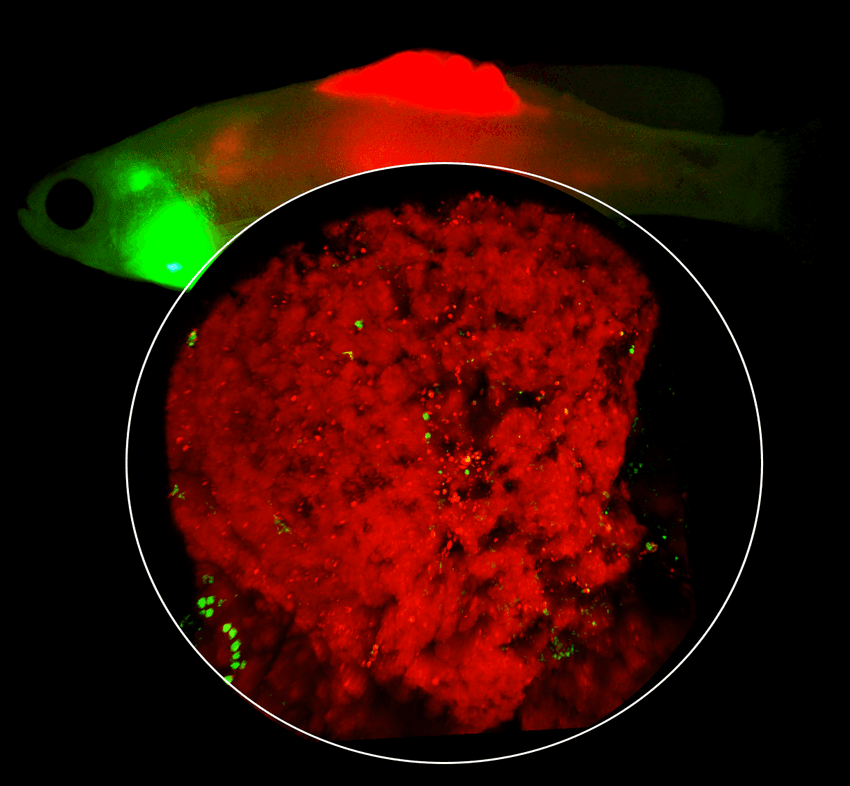

A 3D image of a melanoma tumor (red) growing between the scales of a zebrafish with T cells (green). The T cells home into the black pockets on the melanoma surface called CRATERs.

Aya Ludin (Ludin et al. Zon)

To investigate this, researchers led by Leonard Zon, a cancer and stem cell biologist at Harvard University, tracked T cells in a zebrafish model of melanoma. Their results, published in Cell, describe that T cells aggregate in certain pockets on the cancer cell surface to form prolonged interactions to kill the cells.1 These domains—that the researchers called Cancer Regions of Antigen presentation and T cell Engagement and Retention (CRATERs)—could be used to indicate immunotherapy success in patients.

To examine the interaction between CD8+ T cells and melanoma, Zon and his team generated a zebrafish line wherein the immune cells expressed green fluorescent protein. They then introduced mutations that drove melanoma formation in these zebrafish.

Time-lapse microscopy revealed that CD8+ T cells gathered in specific regions on the melanoma surface. The researchers tracked the cellular dynamics in three dimensions over 15 to 20 hours and observed that the T cells lingered in these CRATERs and engaged with melanoma cells for many hours.

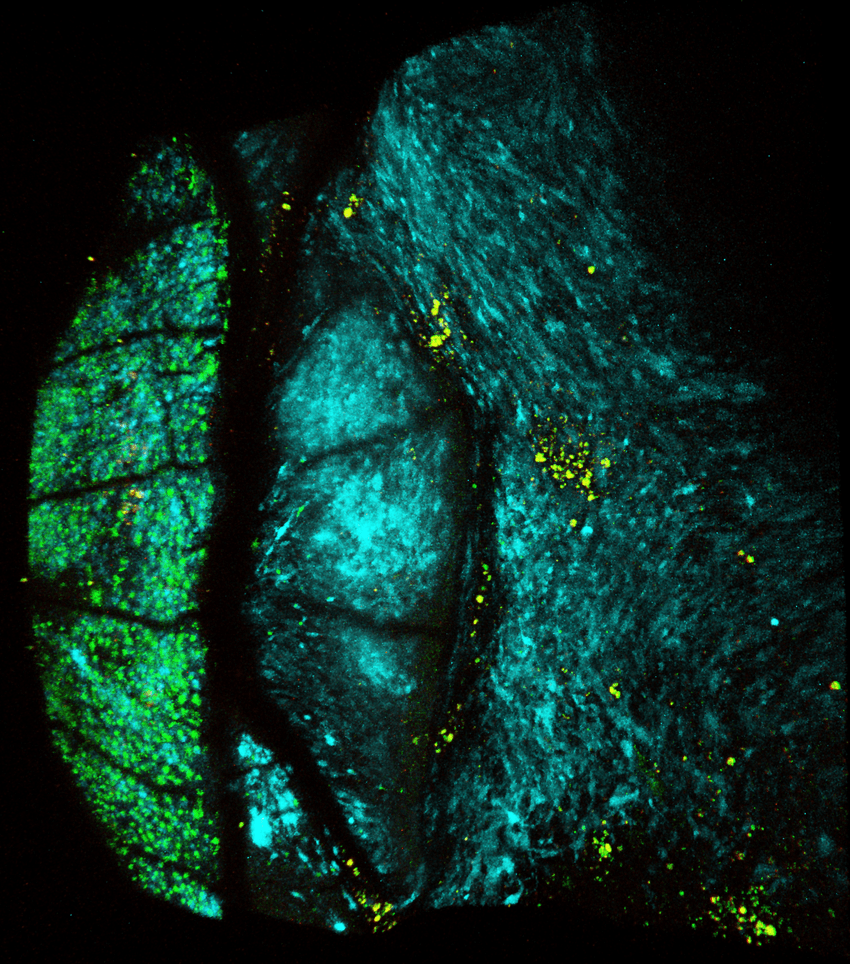

High-resolution spatial transcriptomics helped Zon and his team characterize the genetic landscape of CRATERs. Compared to other cell surface areas, CRATERs showed elevated expression of a gene encoding a protein that helps CD8+ T cells recognize tumors and sustain interactions between the two cell types.

A 3D image of a melanoma tumor (blue) growing between the scales of a zebrafish. T cells (yellow) aggregate inside pockets on the melanoma surface called CRATERs.

Aya Ludin (Ludin et al. Zon)

Next, the researchers treated zebrafish with an immunotherapeutic drug. Compared to controls, immunotherapy significantly increased the cell surface area covered by CRATERs, and consequently CD8+ T cell localization on cancer cells. Assaying DNA fragmentation, a hallmark of apoptosis, revealed that immunotherapy-treated tumors exhibited an increased number of apoptotic cells within CRATERs, indicating that CD8+ T cells gather in these pockets and promote cell death.

Finally, Zon and his team investigated the clinical relevance of their findings. They examined human melanoma tumors using immunofluorescence and observed similar CRATER-like pockets on the cell surface. These regions contained more CD8+ T cells, indicating that the immune cells cluster within CRATERs. Samples from patients who responded well to immunotherapy had a higher CRATER density compared to those from non-responders, suggesting that the extent of CRATERs correlated with immunotherapy success.

“Pending thorough clinical verification and taken together with other measurements, CRATERs may serve to more accurately assess the efficacy of an ongoing treatment and improve treatment outcomes,” said Zon in a press release.

- Ludin A, et al. CRATER tumor niches facilitate CD8+ T cell engagement and correspond with immunotherapy success. Cell. 2025.