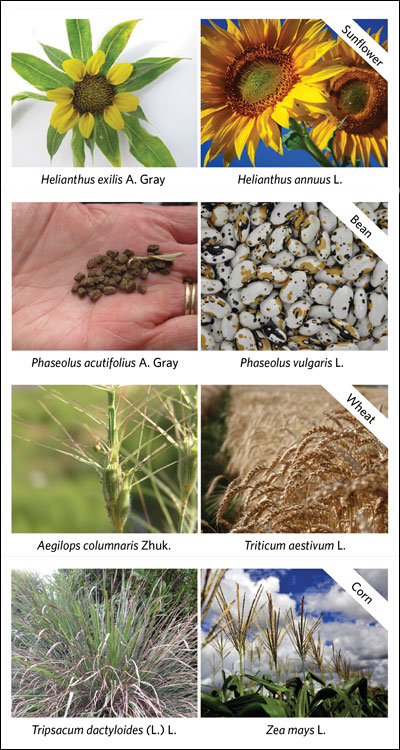

ALL IN THE FAMILY: Wild relatives (left) of important cultivated crops (right) are vital sources of genetic diversity for developing new crop varieties able to withstand challenges ranging from arable land restriction to climate change.Plants closely related to crop species, such as wild maize in Mexico and wild rice in West Africa, often happily grow in and around the disturbed soils of agricultural fields, passing their genes along to these crops with the help of wind and insects. Some traditional farmers even encourage such “weeds” because they recognize that their presence has a positive effect on their crops.

ALL IN THE FAMILY: Wild relatives (left) of important cultivated crops (right) are vital sources of genetic diversity for developing new crop varieties able to withstand challenges ranging from arable land restriction to climate change.Plants closely related to crop species, such as wild maize in Mexico and wild rice in West Africa, often happily grow in and around the disturbed soils of agricultural fields, passing their genes along to these crops with the help of wind and insects. Some traditional farmers even encourage such “weeds” because they recognize that their presence has a positive effect on their crops.

Modern, industrial farms no longer maintain this direct connection between domesticated and wild cousins, but plant breeders have found ways to take advantage of the genetic diversity found in wild relatives to develop new, hardier plant varieties. For a wide and growing range of food, fiber, industrial, ornamental, and other crops, wild relatives have contributed to improved size, taste, and nutritional content; tolerance to abiotic stress; and, most frequently, pest and disease resistance.

Wild relatives are exposed to myriad threats including habitat destruction, introduction of industrial agricultural practices, pollution, invasive species, and climate change. Due to a combination of these pressures, many unique populations of wild relatives of the world’s important crops, such as maize, peanut, potato, and cowpea, are becoming smaller and more fragmented.

...