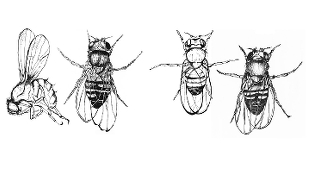

IMAGINAL DISC PRODUCTIONSIn 2004, just as he was starting out on his PhD in genetics at Rockefeller University, New York, Alexis Gambis heard about the Fly Room—a cramped office space at nearby Columbia University where, in the early part of the 20th century, Thomas Hunt Morgan and his protégés reared thousands of fruit flies as part of the experiments that led to the discovery of how genes are arranged on chromosomes and how they encode specific traits. In the process, the researchers established the scientific basis for the modern study of genetics.

IMAGINAL DISC PRODUCTIONSIn 2004, just as he was starting out on his PhD in genetics at Rockefeller University, New York, Alexis Gambis heard about the Fly Room—a cramped office space at nearby Columbia University where, in the early part of the 20th century, Thomas Hunt Morgan and his protégés reared thousands of fruit flies as part of the experiments that led to the discovery of how genes are arranged on chromosomes and how they encode specific traits. In the process, the researchers established the scientific basis for the modern study of genetics.

The work, borne of an egalitarian atmosphere cultivated by Morgan, who encouraged his students to contribute on equal footing, won a Nobel Prize in 1933. “It’s an iconic lab where most of the early discoveries in genetics were made,” says Gambis, who himself worked with fruit flies for his research until he left the lab a few years ago to focus on filmmaking. “It was a bit of a Dead Poets Society; a bunch of guys playing with fruit flies, smoking cigars, and throwing out ideas, all in this badly-lit, dingy little space.”

It was a scene bursting with cinematic potential. And now, almost 10 years after learning of the Fly Room, Gambis has just wrapped shooting for a movie based on the famous lab. ...