Since Henry Bence Jones first discovered a urine protein marker for multiple myeloma in 1846, the field of cancer biomarkers has grown exponentially. Over the past two centuries, scientists have cataloged thousands of tumor markers, ranging from proteins and metabolites to DNA and RNA. In this article, explore the evolving definition of cancer biomarkers, their sources, the techniques used to analyze them, and notable examples.

Cancer biomarkers play an important role in cancer diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. The number of biomarkers and the tests researchers use to analyze them continue to grow each day.

iStock, jarun011

What Are Cancer Biomarkers?

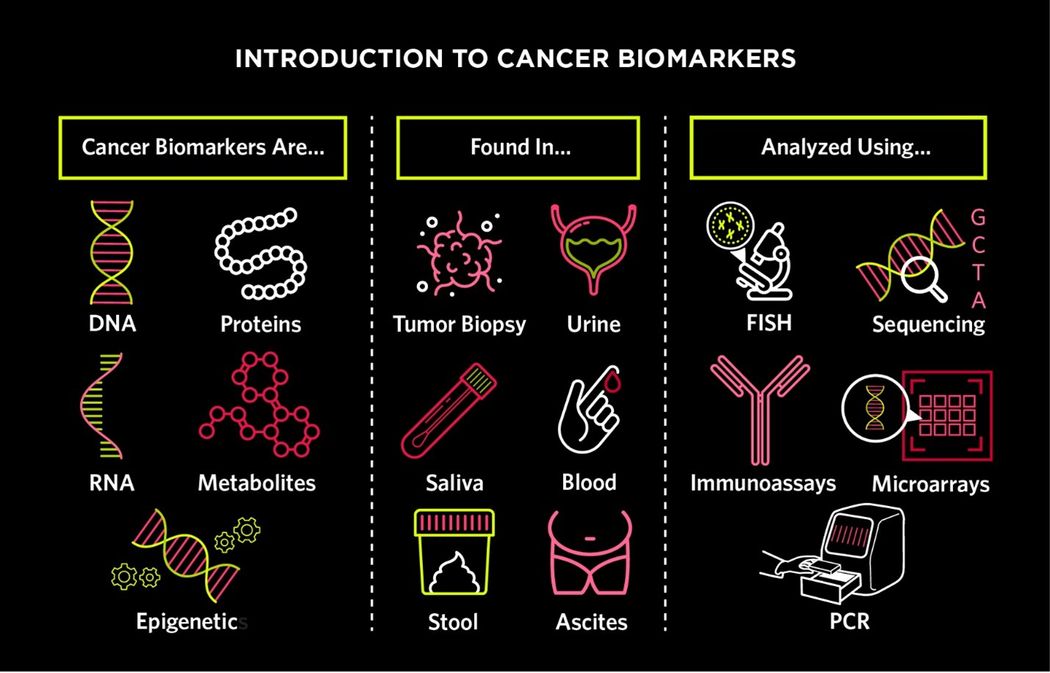

A cancer biomarker is a broad term referring to any biological molecule that indicates the presence of a cancerous process.1 These processes can result from germline or somatic genetic mutations, epigenetic modifications, transcriptional changes, post-translational modifications, and other factors. For instance, genomic changes often manifest as aberrations in biological molecules such as nucleic acids and proteins, which scientists collect from tumor tissue or body fluids.2

Biomarkers that researchers or clinicians identify in a sample may play a role in cancer screening and diagnosis.3 In patients already diagnosed with malignancies, biomarkers can also help doctors predict disease prognosis, assess specific treatment efficacies, and monitor recurrence.4 Ideally, cancer biomarker detection methods should be reliable, reproducible, sensitive, specific, cost-effective, and contribute to improved patient outcomes. From a research perspective, cancer biomarkers help scientists understand disease pathophysiology and develop targeted therapies.

There are many different types of cancer biomarkers, which can be found in tumor tissue or body fluids. Scientists use a range of molecular techniques to analyze cancer biomarkers and gain a better understanding of disease diagnosis, prognosis, and progression.

Modified from © iStock

Where Are Cancer Biomarkers Found?

Scientists commonly search for cancer biomarkers using tissue from a tumor biopsy. Alternatively, researchers can obtain tumor-derived information through a liquid biopsy.5 This less invasive procedure involves sampling body fluids such as whole blood, serum, plasma, stool, urine, sputum, exhaled breath, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, ascites, and more.6

In liquid biopsies, researchers analyze several key components to test for cancer biomarkers.7,8

- Proteins: Proteins were some of the earliest cancer biomarkers detected in liquid biopsies, even before scientists developed DNA sequencing techniques. Protein biomarkers have somewhat limited clinical applications due to their low sensitivity and specificity.9 However, they are important for monitoring disease recurrence for certain malignancies, such as prostate, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers.

- White Blood Cells: Although bone marrow evaluation is considered the gold standard for diagnosing hematological disorders such as leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndrome, peripheral blood analysis can also provide valuable insights.10,11 Researchers may examine white blood cells using conventional molecular techniques to identify large-scale chromosomal changes, such as translocations, or apply big data analysis to detect specific sequence mutations.

- Circulating Tumor Cells: One promising research area focuses on circulating tumor cells (CTCs), which are cells shed from the primary tumor and transported through the lymphatic or circulatory system, potentially contributing to distant metastases.12 Although CTCs are most abundant in blood, they can also be found in other body fluids. CTCs have shown potential as prognostic markers for progression-free survival and overall survival across several cancer types.13 They may also assist doctors in selecting targeted therapies for individual patients.14 Despite its promise, CTC analysis remains challenging due to the rarity of these cells—typically fewer than ten per milliliter of blood—and their short lifespan, as the immune system eliminates most within hours of their release from the tumor.5,7 Additionally, CTCs exhibit considerable heterogeneity and lack a unifying molecular signature, which has made it difficult for researchers to develop a universal isolation technique.6 Currently, clinicians use the FDA-approved CellSearch system to examine CTCs and assess the prognosis of metastatic breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers.5 Researchers are also exploring the use of nanomaterials and microfluidic systems to improve CTC capture and detection.6

- Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) and Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA): Cells release DNA following apoptosis or necrosis, or through active secretion. cfDNA refers to freely circulating DNA that may or may not originate from a tumor. Fragmented tumor DNA in the bloodstream is specifically known as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and accounts for only a small fraction of cfDNA. ctDNA shares many of the same clinical applications as CTCs but also has limitations, including a short half-life and low concentration in bodily fluids.5,15

- Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): EVs are small 30-100 nm lipid-bound vesicles that cells use for a variety of functions, such as eliminating waste products and communicating with other cells. EVs contain biological molecules such as cfDNA, RNA, and proteins that scientists may use to assess and monitor cancer.6

What Techniques Do Scientists Use to Analyze Cancer Biomarkers?

Scientists commonly use immunoassay methods, molecular hybridization technologies, and high-throughput sequencing to identify and analyze cancer biomarkers. While advances in this field continue, the following is a summary of some of the more traditional and widely used approaches for biomarker detection.

Table: Cancer biomarker detection assays

| Mechanism | Pros | Cons

|

Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH)16,17

| FISH is a technique that involves fluorescently labeled probes to target specific chromosomal regions within DNA. In the context of cancer biomarker detection, these probes bind to DNA in tissue samples suspected to contain cancer cells. The fluorescent signals generated after binding allow researchers to identify chromosomal abnormalities, such as duplications, amplifications, insertions, inversions, deletions, or translocations.

| Allows direct visualization of chromosomal regions of interest

Easy preparation

| Limited to large-scale chromosomal abnormalities, cannot detect single point mutations

Difficulty detecting residual disease during or after treatment

Decreased accuracy with unbalanced translocations

|

Immunoassays such as Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF), and ELISA18,19 | IHC and IF involve antibodies that specifically bind to target proteins or glycoproteins, known as antigens, characteristic of certain cancers. Scientists then apply a secondary antibody, coupled with an enzyme or a fluorescent marker, to amplify the signal. This interaction is visualized through chromogenic reactions, producing a color change or fluorescence that highlights the presence and location of the antigen within the tissue sample. Scientists use ELISA to identify protein biomarkers. Much like IHC/IF, this technique involves an antibody and colored substrate to find antigens of interest. | Allows scientists to directly visualize proteins of interest

Well-known research technique

| Interpretation of results can be subjective

Antibody specificity and availability can be limiting

Multi-step process can hinder reproducibility

|

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)20

| Scientists use PCR to examine DNA and RNA alterations such as sequence variations, fusion events, and changes in methylation patterns. PCR is a targeted approach for analyzing a small number of predefined targets.

| Well-known research technique

High specificity and sensitivity

| Limited to known target genes and regions of interested

|

NGS is a high-throughput sequencing method that enables the detection of several DNA and RNA mutations—including single nucleotide variations, insertions, deletions, rearrangements, and methylation alterations—across thousands of genes or even entire genomes. While PCR is used during NGS library preparation to amplify DNA, NGS goes beyond PCR by providing a broader overview of the cancer genome.

| High specificity and sensitivity

High throughput enables comprehensive genome surveillance | Complex technique that requires bioinformatics knowledge and computing capacity

Long wait times for patients to receive result | |

Gene expression microarrays enable simultaneous differential expression analysis of thousands of genes between test and control samples. In this technique, RNA from the samples is converted into fluorescently labeled cDNA, which is then applied to a microarray slide with gene-specific probes. The emitted fluorescent signals indicate gene expression levels, enabling comparison across samples. Tumor cells have a distinct molecular signature that differentiates them from normal tissue or post-treatment cells. | High throughput enables comprehensive genome surveillance

Cancer genome instability means there may be more than one molecular signature for every cancer | Complex technique that requires bioinformatics knowledge and computing capacity Limited to known target genes |

Researchers are continuously discovering new ways to detect cancer biomarkers at low concentrations in body fluids. Examples of emerging methodologies include biosensors, nanotechnology, microfluidics, and CRISPR-based ctDNA and RNA detection. Biosensors use a transducer to convert biological signals from biomarkers into electrical or optical signals that can be amplified and analyzed.24 In CRISPR-based methods, a Cas protein guided by a target biomarker-specific RNA cleaves the region of interest, producing a detectable signal.25 Microfluidic devices, which are often integrated with nanomaterials, enable the isolation and enrichment of CTCs, EVs, and ctDNA.26

Examples of Well-Known Cancer Biomarkers

There are thousands of known biomarkers, including the following.

- Colon cancer biomarkers: Mismatch repair (MMR) is a cellular mechanism that corrects errors that arise during DNA replication and recombination. Mutations in MMR genes, such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, increase the risk of colorectal cancer by impairing this DNA repair process, resulting in microsatellite instability.27 Mutations in MMR genes may serve as biomarkers for disease prognosis or predisposition and can help clinicians select treatment. Changes in the KRAS gene are also well-known cancer driver mutations. Additionally, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a protein biomarker that is elevated in the blood of some patients with colorectal cancer.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma: Alpha-fetoprotein is a glycoprotein that is often elevated in patients with liver cancer. It can also be a marker of germ cell tumors and gastric cancer.28

- Hepatopancreatobiliary cancers: Elevated glycoprotein complex carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) is associated with both pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma.29

- Ovarian cancer: CA125 has a well-known association with ovarian cancer. Its clinical application with respect to diagnosis and screening is limited, but clinicians may use CA125 to monitor for recurrence.30

- Hematological disorders: Hematological disorders have a variety of diagnostic tumor markers, from surface molecules such as CD20, CD25, and CD30 to genomic changes such as the JAK2 mutation in myeloproliferative disorders or the BCR-ABL mutation in chronic myeloid leukemia.2

- Henry NL, Hayes DF. Cancer biomarkers. Mol Oncol. 2012;6(2):140-146.

- Sarhadi VK, Armengol G. Molecular biomarkers in cancer. Biomolecules. 2022;12(8):1021.

- Zhou Y, et al. Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):1-86.

- Passaro A, et al. Cancer biomarkers: Emerging trends and clinical implications for personalized treatment. Cell. 2024;187(7):1617-1635.

- Connal S, et al. Liquid biopsies: The future of cancer early detection. J Transl Med. 2023;21:118.

- Lone SN, et al. Liquid biopsy: A step closer to transform diagnosis, prognosis and future of cancer treatments. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):79.

- Nikanjam M, et al. Liquid biopsy: Current technology and clinical applications. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):131.

- Ma L, et al. Liquid biopsy in cancer: Current status, challenges and future prospects. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):1-36.

- Ding Z, et al. Proteomics technologies for cancer liquid biopsies. Molecular Cancer. 2022;21(1):53.

- Rindy LJ, Chambers AR. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed December 20, 2024.

- Álvarez-Zúñiga CD, et al. Circulating biomarkers associated with the diagnosis and prognosis of B-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(16):4186.

- Lin D, et al. Circulating tumor cells: Biology and clinical significance. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:404.

- Capuozzo M, et al. Circulating tumor cells as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in solid tumors. Cells. 2023;12(22):2590.

- Yu M, et al. Ex vivo culture of circulating breast tumor cells for individualized testing of drug susceptibility. Science. 2014;345(6193):216-220.

- Bronkhorst AJ, et al. The emerging role of cell-free DNA as a molecular marker for cancer management. Biomol Detect Quantif. 2019;17:100087.

- Chrzanowska NM, et al. Use of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in diagnosis and tailored therapies in solid tumors. Molecules. 2020;25(8):1864.

- Hu L, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH): An increasingly demanded tool for biomarker research and personalized medicine. Biomark Res. 2014;2:3.

- Taube JM, et al. The society for immunotherapy of cancer statement on best practices for multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF) staining and validation. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000155.

- Lengfeld J, et al. Challenges in detection of serum oncoprotein: Relevance to breast cancer diagnostics. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2021;13:575-593.

- Scott A, et al. RT-PCR-based gene expression profiling for cancer biomarker discovery from fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. In: Al-Mulla F, ed. Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissues: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; 2011:239-257.

- Chen M, Zhao H. Next-generation sequencing in liquid biopsy: cancer screening and early detection. Human Genomics. 2019;13(1):34.

- Narrandes S, Xu W. Gene expression detection assay for cancer clinical use. J Cancer. 2018;9(13):2249-2265.

- Michiels S, et al. Interpretation of microarray data in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(8):1155-1158.

- Bohunicky B, Mousa SA. Biosensors: The new wave in cancer diagnosis. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2010;4:1-10.

- Huang CH, et al. Applications of CRISPR-Cas enzymes in cancer therapeutics and detection. Trends Cancer. 2018;4(7):499-512.

- Liu Z, et al. Microfluidic biosensors for biomarker detection in body fluids: A key approach for early cancer diagnosis. Biomark Res. 2024;12:153.

- Battaglin F, et al. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer: Overview of its clinical significance and novel perspectives. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2018;16(11):735-745.

- Hanif H, et al. Update on the applications and limitations of alpha-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(2):216-229.

- Lee T, et al. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 — tumor marker: Past, present, and future. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;12(12):468-490.

- Charkhchi P, et al. CA125 and Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):3730.