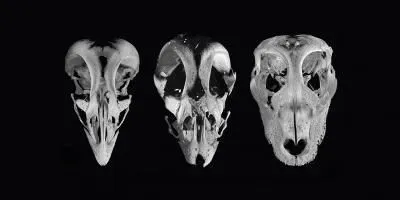

The skull of a normal chicken embryo has a beak (left), but when certain gene expression pathways are blocked (middle) it develops a snout that resembles that of a modern-day alligator (right).IMAGE: BHART-ANJAN BHULLARScientists have created chicken embryos with faces that hearken back to their dinosaur roots, according to research published today (May 12) in Evolution. Researchers at Harvard, Yale, and elsewhere inhibited gene expression pathways in two domains within developing chicken embryos: the frontonasal ectodermal zone (FEZ) and the midfacial Wnt-responsive region. Doing so yielded embryonic chicks with altered facial morphology that looked less like that of a beaked bird and more like the snout of a crocodile or a long-snouted dinosaur. “We’re trying to explain evolution through developmental studies,” Harvard evolutionary developmental biologist and coauthor Arhat Abzhanov told Science.

The skull of a normal chicken embryo has a beak (left), but when certain gene expression pathways are blocked (middle) it develops a snout that resembles that of a modern-day alligator (right).IMAGE: BHART-ANJAN BHULLARScientists have created chicken embryos with faces that hearken back to their dinosaur roots, according to research published today (May 12) in Evolution. Researchers at Harvard, Yale, and elsewhere inhibited gene expression pathways in two domains within developing chicken embryos: the frontonasal ectodermal zone (FEZ) and the midfacial Wnt-responsive region. Doing so yielded embryonic chicks with altered facial morphology that looked less like that of a beaked bird and more like the snout of a crocodile or a long-snouted dinosaur. “We’re trying to explain evolution through developmental studies,” Harvard evolutionary developmental biologist and coauthor Arhat Abzhanov told Science.

The interrupted gene expression pathways are involved in transforming birds’ premaxillae—facial bones that for part of the upper jaw in most vertebrates—into myriad beak forms in about 10,000 species of modern birds. As dinosaurs evolved into birds some 150 million years ago, the premaxillae elongated and fused together to form beaks. “Instead of two little bones on the sides of snout, like all other vertebrates, it was fused into a single structure,” study coauthor and Yale paleontologist Bhart-Anjan Bhullar—now at the University of Chicago—told Nature. Abzhanov, Bhullar, and their colleagues reasoned that by altering gene expression in facial regions that eventually give rise to the premaxillae, they could affect beak formation and, in essence, turn back the evolutionary clock to encourage the formation of a ...