In the home, the lab and the factory, electric fields control technologies such as Kindle displays, medical diagnostic tests and devices that purify cancer drugs. In an electric field, anything with an electrical charge – from an individual atom to a large particle – experiences a force that can be used to push it in a desired direction.

When an electric field pushes charged particles in a fluid, the process is called electrophoresis. Our research team is investigating how to harness electrophoresis to move tiny particles – called nanoparticles – in porous, spongy materials. Many emerging technologies, including those used in DNA analysis and medical diagnostics, use these porous materials.

Figuring out how to control the tiny charged particles as they travel through these environments can make them faster and more efficient in existing technologies. It can also enable entirely new smart functions.

Ultimately, scientists are aiming to make particles like these serve as tiny nanorobots.1 These could perform complex tasks in our bodies or our surroundings. They could search for tumors and deliver treatments or seek out sources of toxic chemicals in the soil and convert them to benign compounds.2,3

To make these advances, we need to understand how charged nanoparticles travel through porous, spongy materials under the influence of an electric field. In a new study, published Nov. 10, 2025, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, our team of engineering researchers led by Anni Shi and Siamak Mirfendereski sought to do just that.4

Weak and Strong Electric Fields

Imagine a nanoparticle as a tiny submarine navigating a complex, interconnected, liquid-filled maze while simultaneously experiencing random jiggling motion. While watching nanoparticles move through a porous material, we observed a surprising behavior related to the strength of the applied electric field.

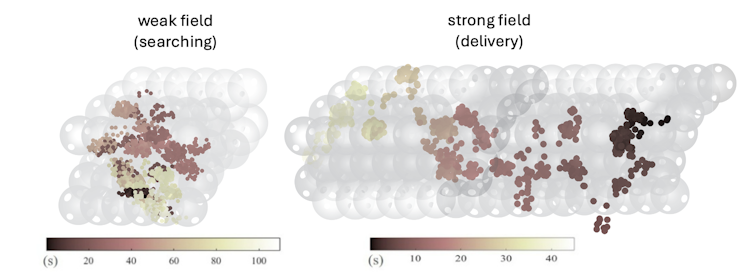

A weak electric field acts only as an accelerator, boosting the particle’s speed and dramatically improving its chance of finding any exit from a cavity, but offering no directional guidance – it’s fast, but random.

In contrast, a strong electric field provides the necessary “GPS coordinates,” forcing the particle to move rapidly in a specific, predictable direction across the network.

This discovery was puzzling but exciting, because it suggested that we could control the nanoparticles’ motion. We could choose to have them move fast and randomly with a weak field or directionally with a strong field.

The former allows them to search the environment efficiently while the latter is ideal for delivering cargo. This puzzling behavior prompted us to look more closely at what the weak field was doing to the surrounding fluid.

By studying the phenomenon more closely, we discovered the reasons for these behaviors. A weak field causes the stagnant liquid to flow in random swirling motions within the material’s tiny cavities. This random flow enhances a particle’s natural jiggling and pushes it toward the cavity walls. By moving along walls, the particle drastically increases its probability of finding a random escape route, compared to searching throughout the entire cavity space.

A strong field, however, provides a powerful directional push to the particle. That push overcomes the natural jiggling of the particle as well as the random flow of the surrounding liquid. It ensures that the particle migrates predictably along the direction of the electric field. This insight opens the door for new, efficient strategies to move, sort and separate particles.

Tracking Nanoparticles

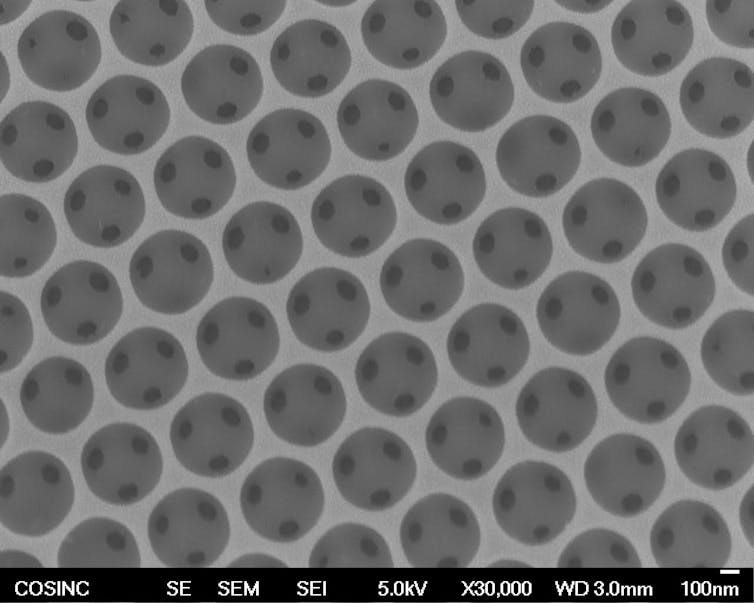

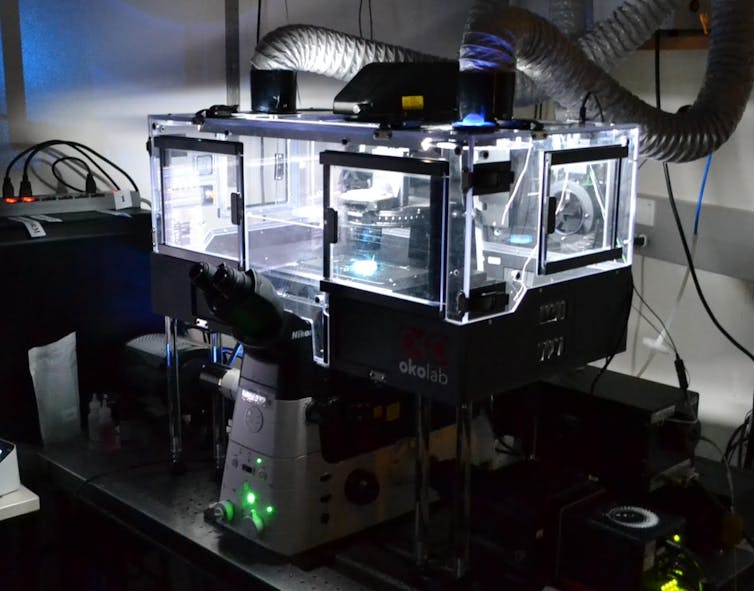

To conduct this research, we integrated laboratory observation with computational modeling. Experimentally, we used an advanced microscope to meticulously track how individual nanoparticles moved inside a perfectly structured porous material called a silica inverse opal.

We then used computer simulations to model the underlying physics. We modeled the particle’s random jiggling motion, the electrical driving force and the fluid flow near the walls.

By combining this precise visualization with theoretical modeling, we deconstructed the overall behavior of the nanoparticles. We could quantify the effect of each individual physical process, from the jiggling to the electrical push.

Devices That Move Particles

This research could have major implications for technologies requiring precise microscopic transport. In these, the goal is fast, accurate and differential particle movement. Examples include drug delivery, which requires guiding “nanocargo” to specific tissue targets, or industrial separation, which entails purifying chemicals and filtering contaminants.5,6

Our discovery – the ability to separately control a particle’s speed using weak fields and its direction using strong fields – acts as a two-lever control tool.

This control may allow engineers to design devices that apply weak or strong fields to move different particle types in tailored ways. Ultimately, this tool could improve faster and more efficient diagnostic tools and purification systems.

What’s Next

We’ve established independent control over the particles’ searching using speed and their migration using direction. But we still don’t know the phenomenon’s full limits.

Key questions remain: What are the upper and lower sizes of particles that can be controlled in this way? Can this method be reliably applied in complex, dynamic biological environments?

Most fundamentally, we’ll need to investigate the exact mechanism behind the dramatic speedup of these particles under a weak electric field. Answering these questions is essential to unlocking the full precision of this particle control method.

Our work is part of a larger scientific push to understand how confinement and boundaries influence the motion of nanoscale objects. As technology shrinks, understanding how these particles interact with nearby surfaces will help design efficient, tiny devices. And when moving through spongy, porous materials, nanoparticles are constantly encountering surfaces and boundaries.

The collective goal of our and others’ related research is to transform the control of tiny particles from a process of trial and error into a reliable, predictable science.7![]()

Daniel K. Schwartz, Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder and Ankur Gupta, Assistant Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Ju X, et al. Technology roadmap of micro/nanorobots. ACS Nano. 2025;19(27):24174-24334.

- Nelson BJ, Pané S. Delivering drugs with microrobots. Science. 2023;382(6675):1120-1122.

- Hou J, et al. Recent advances in micro/nano-robots for environmental pollutant removal: Mechanism, application, and prospect. Chem Eng J. 2024;498:155135.

- Shi A, et al. Electrokinetic nanoparticle transport in an interconnected porous environment: Decoupling cavity escape and directional bias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025;122(46):e2514874122.

- Luo M, et al. Micro-/Nanorobots at Work in Active Drug Delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018;28:1706100.

- Zhu Z, et al. Protein separation by capillary gel electrophoresis: A review. Anal Chim Acta. 2012;709:21-31.

- Chepizhko O, Peruani F. Diffusion, subdiffusion, and trapping of active particles in heterogeneous media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;111:160604.