WIKIMEDIA, YALE ROSENHow humans respond to the pathogens they encounter has less to do with genetics than with their previous exposure to viruses and bacteria, a study of twins published this week (January 15) in Cell has found. By measuring over 200 immune system parameters—such as blood protein levels or the number of immune cells—in 210 identical or fraternal twins, a team led by Mark Davis of Stanford University found that environmental factors were more influential than genetic ones in determining the variation between twins more than 75 percent of the time. For over half of the measured parameters, environmental influences accounted for most of the difference. The study participants ranged in age from 8 to 82 years old, and the younger twins, likely exposed to the same environment as each other, showed greater similarities in their immune systems than older ones.

WIKIMEDIA, YALE ROSENHow humans respond to the pathogens they encounter has less to do with genetics than with their previous exposure to viruses and bacteria, a study of twins published this week (January 15) in Cell has found. By measuring over 200 immune system parameters—such as blood protein levels or the number of immune cells—in 210 identical or fraternal twins, a team led by Mark Davis of Stanford University found that environmental factors were more influential than genetic ones in determining the variation between twins more than 75 percent of the time. For over half of the measured parameters, environmental influences accounted for most of the difference. The study participants ranged in age from 8 to 82 years old, and the younger twins, likely exposed to the same environment as each other, showed greater similarities in their immune systems than older ones.

“What we found was that in most cases, including the reaction to a standard influenza vaccine and other types of immune responsiveness, there is little or no genetic influence at work, and most likely the environment and your exposure to innumerable microbes is the major driver,” Davis said in a statement.

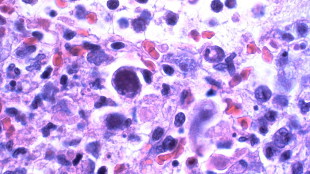

One of the largest environmental causes of immune differences between the twins was the presence cytomegalovirus, a usually harmless chronic infection harbored by three in five Americans. Sixteen of the 27 pairs of identical twins had one infected and one non-infected twin, and in these cases, the researchers found that the cytomegalovirus alone explained over half of the differences between the two siblings’ immune systems.