Nearly eight to 12 percent of couples all over the world face fertility issues, with male infertility accounting for almost 50 percent of the cases.1 A common cause of male infertility is errors during the development of sperm cells, or spermatogenesis, that impede sperm from swimming toward egg cells to fertilize them.

The centriole, an organelle that forms the spindle fibers needed for cell division and flagella that power sperm motility, undergoes major changes during spermatogenesis, aiding in these processes.2 However, the ultrastructural changes—which are visible at higher magnifications—that occur in centrioles during spermatogenesis and the molecular mechanisms behind them remain unclear.

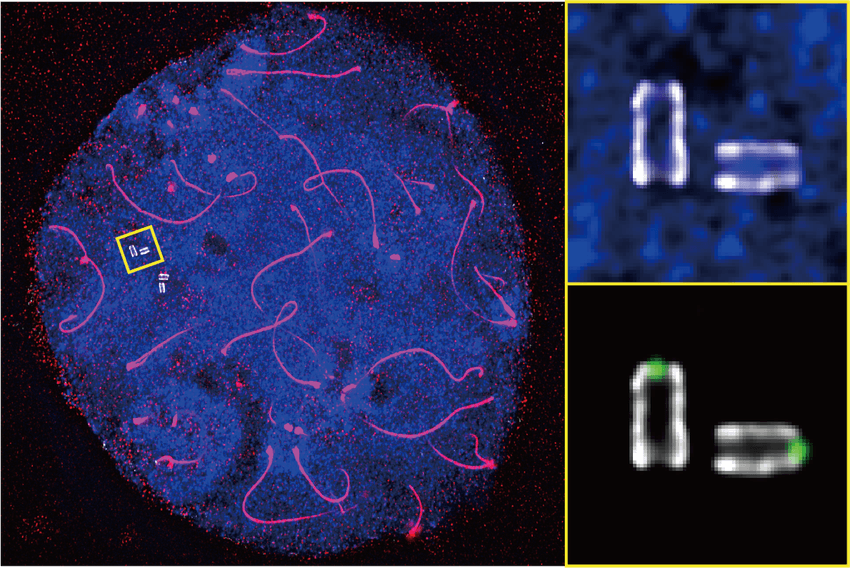

Ultrastructure expansion microscopy of murine male germ cells revealed the fine molecular structures of centrioles (depicted in the enlarged image) against DNA (blue) and chromosome axis (red).

RIKEN

Now, researchers led by RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research biologist Hiroki Shibuya applied an advanced microscopy technique and observed unexpected centriolar architectural changes in mouse germ cells during spermatogenesis.3 Their results, published in Science Advances, reveal a critical molecular mechanism that influences reproductive success.

To peek into sperm cells, Shibuya and his team turned towards ultrastructure expansion microscopy. This technique involves embedding cells within a swellable polymer hydrogel and expanding this gel, allowing for the visualization of nanoscale structures at a high resolution. The researchers optimized this protocol for mouse sperm cells, which helped them observe the barrel-like morphology of centriolar microtubule structures.

Tracing centrioles through each developmental stage of male germ cells revealed the gradual changes from spermatocytes to their next developmental stage, spermatids. The researchers fluorescently labeled two proteins important for assembling and maintaining the structure of the centriole: centrin and POC5. As sperm development progressed, they observed an increase in centrin-POC5 complexes in the inner scaffold within the centriole lumen at the distal tip of the sperm.

To better understand the role of these centrin-POC5 complexes, Shibuya and his team generated Poc5 knockout mice using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. The epididymis—which connects the testicles to vas deferens—of these animals contained no sperm cells, which led to complete infertility.

Microscopy revealed that POC5 depletion prevented the localization of centrin to the inner scaffold, and these spermatids lacked flagellar microtubules that would normally extend from the distal tip centrioles. In contrast, these structures were present in wild type (WT) spermatids, suggesting that absence of centrin-POC5 complexes impedes flagellar assembly.

Using immunofluorescence microscopy, the researchers observed that flagella began to emerge from distal tip centrioles in WT spermatids, progressively elongating as spermatid maturation proceeded. However, Poc5 knockout spermatids showed frayed and disorganized flagellum-like structures which eventually degenerated, explaining the infertility.

“Our modified expansion microscopy protocol can be extended to other analyses, including human sperm, opening new possibilities for investigating fine structural abnormalities that account for male infertility,” said Shibuya in a statement. “In the long-term, this could lead to novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in reproductive medicine.”

- Agarwal A, et al. Male infertility. Lancet. 2021;397(10271):319-333.

- Carvalho-Santos Z, et al. Evolution: Tracing the origins of centrioles, cilia, and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2011;194(2):165-75.

- Takeda Y, et al. Centrin-POC5 inner scaffold provides distal centriole integrity for sperm flagellar assembly. Sci Adv. 2025.