© SEBASTIAN JANICK/© SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

© SEBASTIAN JANICK/© SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

Contrary to the din of some warm summer nights, with choruses of grasshoppers, katydids, crickets, or cicadas chirping away, relatively few insects use acoustic information to communicate with their peers. In fact, outside of these familiar groups, only a very few moth, butterfly, and fly species produce calls. For the insects that do, however, researchers say that sounds they make constitute “singing.”

Contrary to the din of some warm summer nights, with choruses of grasshoppers, katydids, crickets, or cicadas chirping away, relatively few insects use acoustic information to communicate with their peers. In fact, outside of these familiar groups, only a very few moth, butterfly, and fly species produce calls. For the insects that do, however, researchers say that sounds they make constitute “singing.”

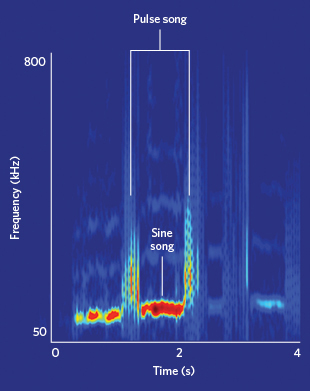

HIGH-FREQUENCY FLY CRIES: Using wing vibrations, Drosophila males can produce two different song modes—pulse and sine—varying the ratio and pattern of the two types depending on the situation.COURTESY OF PIP COEN“I don’t want to get caught up in semantics, but it basically has to do with using sound as a means of sending information,” says evolutionary biologist Michaël Greenfield of CNRS’s insect research institute (Institut de Recherche sur la Biologie de l’Insecte) at the University of Tours in France. “If they make a sound, we call it a song.”

HIGH-FREQUENCY FLY CRIES: Using wing vibrations, Drosophila males can produce two different song modes—pulse and sine—varying the ratio and pattern of the two types depending on the situation.COURTESY OF PIP COEN“I don’t want to get caught up in semantics, but it basically has to do with using sound as a means of sending information,” says evolutionary biologist Michaël Greenfield of CNRS’s insect research institute (Institut de Recherche sur la Biologie de l’Insecte) at the University of Tours in France. “If they make a sound, we call it a song.”

Most insect sounds are relatively simple. In crickets and related species, for example, males repeatedly produce a simple chirp—made by rubbing the top edge of one wing across serrations on the other wing—to attract mates. (In a few species, females are known to duet with males.) But a group of crickets chirping in the same vicinity can produce something quite complex indeed. As in frogs and toads, the sum of the population’s calls is termed ...