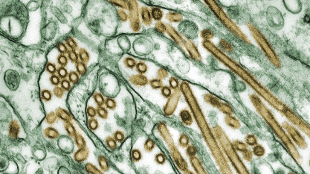

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (in gold)WIKIMEDIA, CDCWhen a new influenza pandemic emerges, researchers struggle to produce vaccines for new strains quickly enough to stop the outbreak in its tracks. Scientists have also been unable to design a universal vaccine that triggers the production of antibodies capable of fighting a range of different strains. But there may be an alternative, albeit temporary, strategy: researchers have now demonstrated that a technique involving the delivery of genes into the nasal passage via a viral vector provided protection against a wide variety of flu strains in mice and ferrets. The findings were published this week (May 30) in Science Translational Medicine.

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (in gold)WIKIMEDIA, CDCWhen a new influenza pandemic emerges, researchers struggle to produce vaccines for new strains quickly enough to stop the outbreak in its tracks. Scientists have also been unable to design a universal vaccine that triggers the production of antibodies capable of fighting a range of different strains. But there may be an alternative, albeit temporary, strategy: researchers have now demonstrated that a technique involving the delivery of genes into the nasal passage via a viral vector provided protection against a wide variety of flu strains in mice and ferrets. The findings were published this week (May 30) in Science Translational Medicine.

The study is an “important proof of concept,” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who was not involved with the research, told The Wall Street Journal. But it remains to be seen if the method will be safe and effective in humans, he added.

According to ScienceNOW, James Wilson of the University of Pennsylvania was prompted by a discussion with Bill Gates in 2010 to see if adeno-associated virus (AAV)—a gene therapy tool previously used in animal studies to deliver genes to treat cystic fibrosis and AIDS—could courier genes encoding influenza antibodies into the noses of mammals, the site of initial infection.

After engineering an AAV to deliver the gene for a “broadly neutralizing antibody” that tackles various flu ...