Grant writing is a core part of scientists’ careers. This skill shapes their funding ability and, in turn, their research capacity. However, many researchers find when they set out to write their first grant that they aren’t prepared for this particular task.

Nicole Coufal studies how genetics and the environment interact during neurological injury and neuroimmunology. As an early-career researcher in 2019, she took UCSD’s Grant Writing Course to prepare to submit her first R01.

Kyle Dykes/UC San Diego Health Sciences

For example, Nicole Coufal, today a physician-scientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), worked on stem cells for her graduate work during a time when the federal government had a moratorium on funding this research; as a result, she didn’t write a research grant for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest funding agency in the US. Even after she completed her medical training, she never had the opportunity to write an R01-style grant. “I realized that was a really big hole in my education that I needed to rectify,” she said.

These gaps can have consequences on scientists’ career success. For example, Donald Chi, a pediatric dentist at the University of Washington who has reviewed grants for more than a decade, said, “When you read a grant and you feel like—regardless of whether the person is a first-time grant writer or an experienced grant writer—that they did not get good feedback that was incorporated, that's, I think, when scoring starts to spiral down. Those grants don't do well.” He added that although not all applications indicate if a proposal is from a first-time grant writer, “you can tell whether someone is a first-time grant writer who did not get mentorship on writing the grant versus someone who got a lot of feedback and incorporated that feedback.”

JoAnn Trejo, a cell biologist and the senior assistant vice chancellor for health sciences faculty affairs at UCSD, also said she had never been explicitly trained on how to write a grant and that there is still not a comprehensive curriculum for this in academic training. In a previous role, she developed a program to help postdoctoral researchers write fellowship proposals. When she started in her role overseeing faculty affairs, she realized that the institution didn’t have a similar resource to help faculty with grant writing.

To help early career researchers like Coufal, Trejo reached out to her colleagues to create a grant writing course for these faculty and collected information from the participants to evaluate its success in helping researchers achieve grant funding. In a study published in Academic Medicine, they showed that the success rate in grant submission from course participants exceeded that of the funding rate for first-time applicants across NIH grant submissions.1 Participants also rated their confidence in key areas of grant writing skills as higher after taking the course. The findings support the implementation of programs like grant writing courses for faculty professional development.

Trejo and her colleagues organized their course based on a guide written for NIH grant applicants. The course incorporated senior faculty experience and guidance, active grant writing, and peer feedback into the curriculum that lasted for three months over nine sessions. All participants had to be at a career stage where they were prepared to submit an R01-style grant but had not received this type of grant or an equivalent to it previously.

To evaluate the impact of the course on early career faculty’s grant writing outcomes, Trejo and her team focused on classes between 2017, the inaugural group, and 2021, since this was the latest group for which the researchers would have two years of follow-up data. This included 85 faculty, but only 82 responded to the survey.

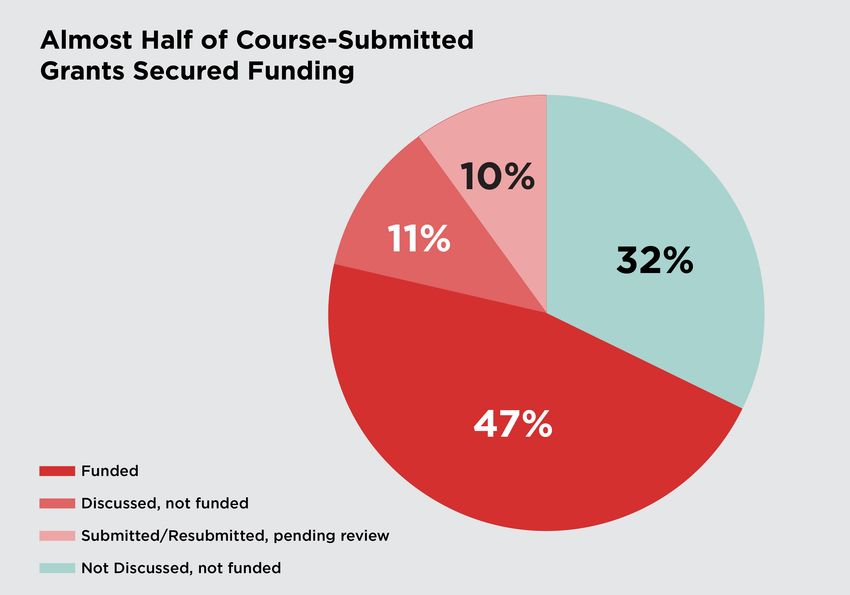

Within two years of completing their respective grant writing courses, 71 participants submitted the proposal that they worked on during the course. The study team found that the majority of these proposals were funded.

Designed by Erin Lemieux; data adapted from LaCroix et al, 2026.

The team found that, within two years of the course, 71 of the participants had submitted the proposal that they brought to the course, and another eight had submitted a different proposal for funding. Of the course-developed grants that the early career faculty submitted, 33 were funded and eight were discussed without funding.

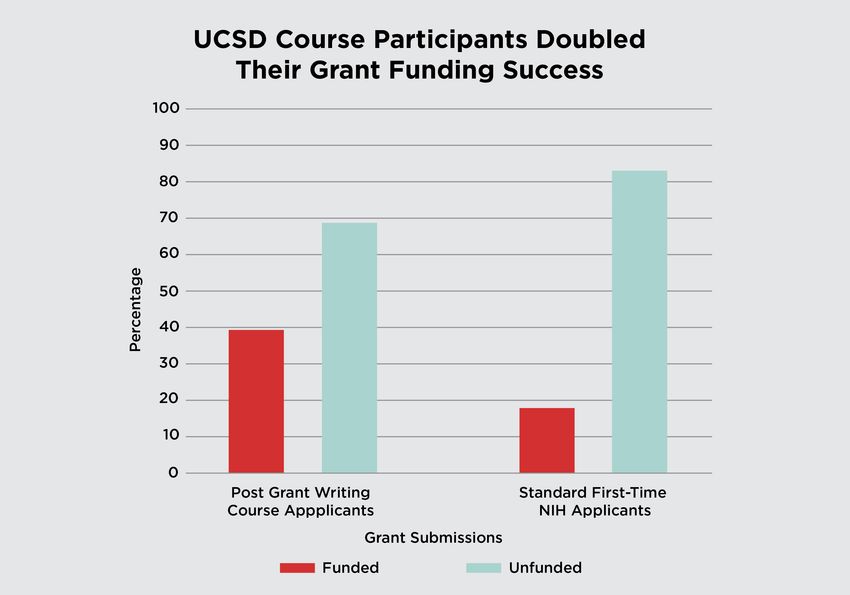

Overall, the participants submitted 460 grants over the study period, and 163 were funded; this funding rate, 35 percent, was nearly double that of the NIH funding rate for first-time applicants in 2023, which was 19 percent. “That was a surprise and very gratifying to know that this is really helping our faculty,” Trejo said.

Coufal, who enrolled in the course in 2019, said that the combination of critiques from senior faculty and peers helped her refine her proposal by identifying holes in her writing and improving how she communicated her ideas. “It was really instrumental in helping to give me a framework for how to convey science and what the pieces need to be and how to think about structuring a question and conveying it to somebody else,” she said.

In total, 79 participants submitted grants in the two years after the grant writing course, for a total of 460 grants; 163, or 35 percent, of these grants were funded, exceeding the NIH funding rate of 19 percent for 2023.

Designed by Erin Lemieux; data adapted from LaCroix et al, 2026.

Chi, who was not involved with the course or the study, identified another benefit to this type of resource. “The real value of these programs is that it sets aside specified times during the week where you're held accountable to think about these ideas, and you have senior mentors who are there to walk you through the process,” he said. He added that the mock study section that the course included would also be useful to participants because it would allow them to see what sorts of questions and problems arise during grant review.

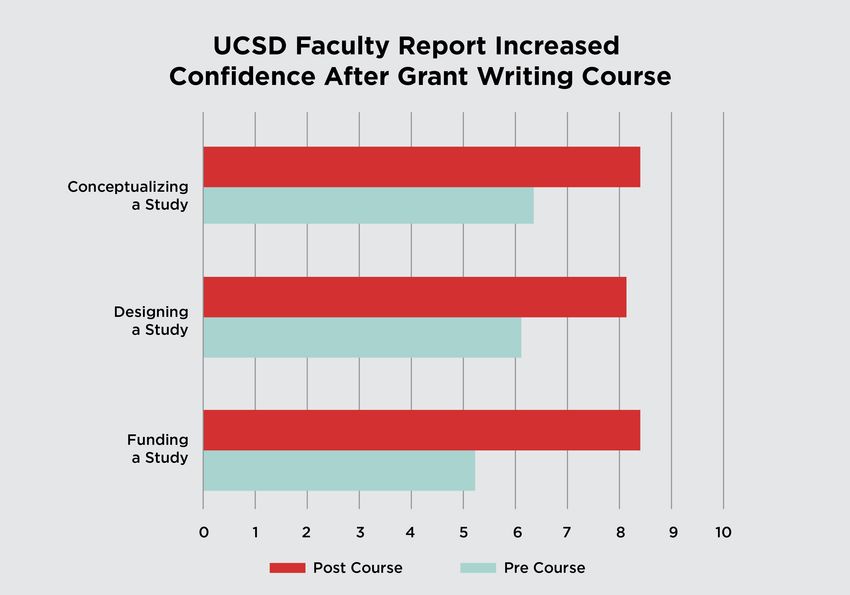

Trejo and her group also assessed the faculty’s confidence in key grant writing skills using the Grantsmanship Self-Efficacy Inventory, which included several statements about grant funding, study design, and study conceptualization. The participants completed this assessment before the course and then immediately after, one year later, and two years later.

The study team saw increases across all 19 metrics, with the greatest increases in statements related to funding a study seeing the highest increase in overall researcher confidence. While all of the scores declined over time, they remained above baseline even two years after completing the course.

“If I had to speculate why that is, it's because then people experience the reality of having a grant maybe not get scored high or funded or the critiques being pretty intense, which [I] can sort of imagine temper some of that sense of self-efficacy,” said Anne Weber-Main, a researcher at the University of Minnesota who explores how interventions improve faculty grant writing.

Participant confidence across all grantsmanship metrics increased after completing the grant writing course. Examples of statements that faculty rated their confidence in include “Convincing grant reviewers your proposed study is worth funding” and “Describing a major funding agency's proposal review and award process.”

Designed by Erin Lemieux; data adapted from LaCroix et al, 2026.

Weber-Main was not involved in the study, but she helped develop the grantsmanship survey that the researchers used in the study. She added that the findings from this work mirror those from programs that other institutions have developed and assessed. Weber-Main said that, although these analyses are descriptive in nature, they strongly support the idea that these resources benefit researchers.

Coufal said that the course was a great opportunity to learn how to write each section of a grant and receive granular feedback from senior faculty. She added that she has also been able to take these lessons and help the people in her lab improve their grant writing skills. The course also inspired her to provide detailed feedback to other physician-scientists junior to herself. “I realized how incredibly valuable that was for me and [was] really what I was looking for at that career stage,” she said.

About the course overall, Coufal said, “The skills they gave me were skills not for one grant but skills for life, and so that was really helpful [and] really, really, tremendously career impactful because without money you can't do the rest of science. It doesn't matter how good your ideas are.”

Trejo echoed this, saying, “We haven't done a rigorous return on investment, but it behooves institutions to implement something like this model because it increases the success of their faculty getting funding, which brings in more revenue to the institutions.”

- LaCroix AZ, et al. Building strong grant writers in academic medicine: Outcomes of early-career faculty enrolled in the University of California San Diego Health Sciences Grant Writing Course. Acad Med. 2026;wvaf031.