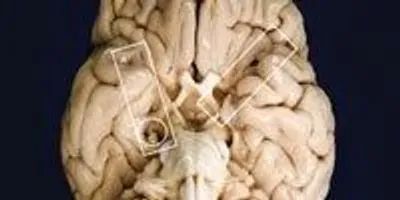

THE SCARS THAT TAUGHT US: The ventral side of H.M.’s brain shows evidence of the surgical scars left by William Beecher Scoville’s 1956 surgery (A and B), which removed portions of the medial temporal lobe, including much of the hippocampus. Also visible is a mark left by one of the surgical clips (C). During the post-mortem analysis, examiners found an unexpected lesion in the orbitofrontal region (D). The portion of H.M.’s hippocampus that remained after the surgery is not visible in this image. (Scale bar, 1 cm)THE BRAIN OBSERVATORY, JACOPO ANNESEIn 1953, William Beecher Scoville performed an experimental procedure on a 27-year-old man who had exhausted all other medical options for treating his severe epilepsy. A medial temporal lobe resection removed most of the patient’s hippocampus, along with pieces of neighboring regions. It succeeded in nearly eliminating the seizures, but left the young man without the ability to form any new memories.

THE SCARS THAT TAUGHT US: The ventral side of H.M.’s brain shows evidence of the surgical scars left by William Beecher Scoville’s 1956 surgery (A and B), which removed portions of the medial temporal lobe, including much of the hippocampus. Also visible is a mark left by one of the surgical clips (C). During the post-mortem analysis, examiners found an unexpected lesion in the orbitofrontal region (D). The portion of H.M.’s hippocampus that remained after the surgery is not visible in this image. (Scale bar, 1 cm)THE BRAIN OBSERVATORY, JACOPO ANNESEIn 1953, William Beecher Scoville performed an experimental procedure on a 27-year-old man who had exhausted all other medical options for treating his severe epilepsy. A medial temporal lobe resection removed most of the patient’s hippocampus, along with pieces of neighboring regions. It succeeded in nearly eliminating the seizures, but left the young man without the ability to form any new memories.

For the next half century, that patient, known as H.M., would become the most studied man in neuroscience. His memory dysfunction helped neuroscientists understand the critical role the hippocampus plays in receiving, processing, and consolidating sensory input. Nearly 100 researchers have studied him, including Suzanne Corkin, who met H.M. in 1962 when she was a graduate student and went on to work closely with him for nearly five decades. Now a professor emerita at MIT, Corkin describes her long-time subject as gentle, intelligent, and gregarious. It was not until 2008, when he died at 82, that H.M.’s identity and real name, Henry Gustave Molaison, was revealed to the world.

On the night Molaison died, doctors set in motion a plan arranged years in advance to ...