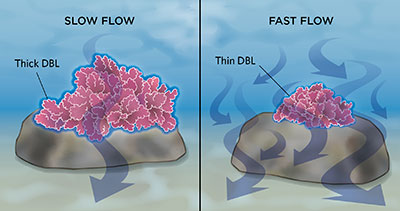

GOING WITH THE FLOW: Coralline algae (pink) exposed to slow-flowing, acidified seawater (left) grew better, protected from the acidity by a thick layer of undisturbed water called the diffusion boundary layer (DBL). In fast-flowing, acidic seawater (right), the algae fared much worse: the DBL thinned, the plants’ calcium carbonate stores dissolved, and their growth diminished. © KIMBERLY BATTISTA

GOING WITH THE FLOW: Coralline algae (pink) exposed to slow-flowing, acidified seawater (left) grew better, protected from the acidity by a thick layer of undisturbed water called the diffusion boundary layer (DBL). In fast-flowing, acidic seawater (right), the algae fared much worse: the DBL thinned, the plants’ calcium carbonate stores dissolved, and their growth diminished. © KIMBERLY BATTISTA

The paper

C.E. Cornwall et al., “Diffusion boundary layers ameliorate the negative effects of ocean acidification on the temperate coralline macroalga Arthrocardia corymbosa,” PLOS ONE, 9:e97235, 2014.

Anthropogenic ocean acidification threatens the survival of countless species and the delicate marine environments they live in. To understand these changes, Catriona Hurd of the University of Tasmania in Australia and colleagues have been measuring how a reduction in pH affects coastal seaweed communities, in particular, coralline algae—red algae that form calcite deposits in their cell walls. Covering much of the rocky surface of intertidal regions globally, coralline algae provide settlement cues, biological signals that recruit the mobile larvae of sponges and other marine invertebrates to attach permanently to a substrate.

For coralline algae and other calcareous species, ...