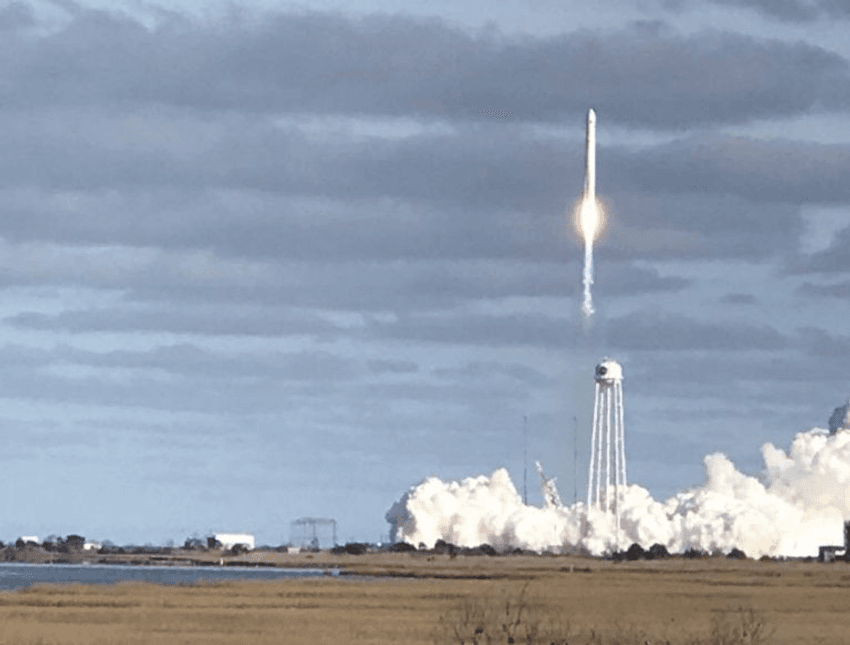

About six years ago, Srivatsan Raman, a biochemist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and his team took a trip to NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. Standing a mile away from the center’s launch pad, the researchers observed a rocket lifting off. Nested within that rocket, riding the countdown towards space, sat vials containing bacteria and bacteria-infecting viruses—bacteriophages—packed and frozen weeks ago.

“It was very surreal...This simple box that was living on the shelf in my lab is now aboard the rocket,” recalled Raman. “[It] was a crazy thing to consider.”

Raman and his team sent bacteria and bacteriophages to space to study how microgravity influenced the microbes’ interactions.

Srivatsan Raman

By conducting experiments on the space-bound microbes once they were back on Earth, Raman and his team found that the dynamics of virus-bacteria interactions in space differed from those in terrestrial conditions.1 The microbes also acquired distinct mutations on Earth and in space. The results, published in PLoS Biology, laid the groundwork for future investigations into how space conditions influence phage-host interactions in commensal microbial communities.

“To my knowledge, there is not really a lot [known] about virus and microbe interactions in space,” said Rosa Santomartino, a space biologist and biotechnologist at Cornell University, who was not associated with the study. “So, from this perspective [this study] is quite a step ahead on what we know.”

It all started when Raman’s team sought to explore how microgravity would affect the microbiome—which consists of both bacteria and bacteriophages—of astronauts. Bacteria and phages tumble around and bump into each other on Earth.2 “In microgravity, the mixing properties are different,” explained Raman. “So that led us to question how phage-host interactions would change in the microbiome [in space].”

This set in motion a series of experiments on Earth, followed by permission to send a mixture of bacteria and bacteriophages aboard the International Space Station. Coming up with a viable plan was not straightforward, recalled Raman. “Real estate on the International Space Station is very expensive,” he said. “So, [NASA] said you can do an experiment as long as you can fit it into a tiny box.”

By running several experiments, Raman and his team designed a small and simple set-up. They mixed a defined volume of Escherichia coli bacteria with different amounts of T7 phages, froze the vials, and shipped them to NASA to investigate how microgravity affected bacteriophage infection of bacteria.

Once aboard the International Space Station, astronauts thawed these vials and incubated them for different time periods, before refreezing them and sending them back to Earth. Upon receiving the vials back from space, Raman and his team thawed the samples and either measured the phage and bacteria amounts or isolated DNA from them. The researchers performed the same experiment with samples on Earth as a control.

Titration of phage and bacteria incubated on Earth revealed that phage infection occurred between two and four hours. In contrast, microbes incubated in space showed delayed infection, suggesting that bacteriophage T7 activity is reduced in microgravity. However, despite the initially delayed activity, T7 eventually successfully infected E. coli.

Raman and his team then sought to identify the mutations in the bacterial and phage genomes that influenced their interactions. Whole genome sequencing revealed that E. coli and T7 bacteriophages accumulated distinct genetic mutations in space and on Earth. While bacteriophages incubated in space acquired mutations that could boost their ability to bind to bacterial cells, microgravity enriched bacterial mutations that helped the microbes manage environmental stress and resist viral infection.

To better understand bacteria-phage interactions in microgravity, the researchers applied a high-throughput method called deep mutational scanning on the T7 receptor binding protein, which recognizes and binds onto the host E. coli surface. They observed stark differences in the number and position of mutations between terrestrial and microgravity conditions. Mutations accumulated in the latter condition facilitated the binding of the phage with the host receptor, boosting phage infectivity in space.

Raman and his team members, Phil Huss and Chutikarn Chitboonthavisuk, visited NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility to observe their experimental setup being launched into space.

Srivatsan Raman

Finally, the researchers investigated whether enrichment of these mutations would enhance phage activity on Earth. They constructed a library containing some of the microgravity-selected mutations and treated clinically isolated urinary tract infection-causing E. coli with these. These phages infected E. coli strains which were resistant to wild type T7 phages, highlighting that microgravity enriched for viral mutations with enhanced terrestrial infection activity.

“We were not quite expecting to see this,” said Raman. “It tells you that you can take natural phages, make modifications to them, and then make them highly effective against pathogens.”

According to Santomartino, the results are intriguing. While it is a little early to say that the findings may have applications in fighting antimicrobial resistance, “it's definitely a step ahead in this direction,” she noted.

More importantly, these findings reveal that astronauts’ gut microbiomes may accumulate mutations, warranting further studies into what happens to their microbiomes when they are back on Earth. Despite this, she noted that the researchers used only one species of bacterium and bacteriophage, which does not give a full picture of community-wide dynamics.

“We’re barely scratching the surface. This hardly represents the complexity of the microbiome,” agreed Raman. “But this very reductionist system is still informative. It tells you that something fundamentally different is at play.”

- Huss P, et al. Microgravity reshapes bacteriophage-host coevolution aboard the International Space Station. PLoS Biol. 2026;24(1):e3003568.

- Abedon ST. Bacteriophage adsorption: Likelihood of virion encounter with bacteria and other factors affecting rates. Antibiotics. 2023;12(4):723.