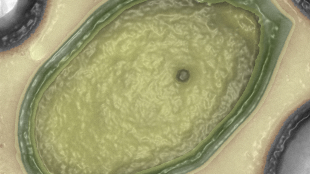

Electron microscopy image of a Pandoravirus particle (edited using Adobe Photoshop artistic filters)COURTESY OF CHANTAL ABERGEL / JEAN-MICHEL CLAVERIEResearchers have discovered two giant viruses, the size of small bacterial cells, that could change the way that science views viral diversity. At around 1 micrometer long and 0.5 micrometers across, the new viruses are larger than even some eukaryotic cells. And within their impressive genomes, which contain 1.9 million and 2.5 million bases, only 7 percent of the genes have matches in genetic databases. The researchers published their findings about the viruses—which they dubbed Pandoraviruses for the “Pandora’s box” of questions they open—last week (July 18) in Science.

Electron microscopy image of a Pandoravirus particle (edited using Adobe Photoshop artistic filters)COURTESY OF CHANTAL ABERGEL / JEAN-MICHEL CLAVERIEResearchers have discovered two giant viruses, the size of small bacterial cells, that could change the way that science views viral diversity. At around 1 micrometer long and 0.5 micrometers across, the new viruses are larger than even some eukaryotic cells. And within their impressive genomes, which contain 1.9 million and 2.5 million bases, only 7 percent of the genes have matches in genetic databases. The researchers published their findings about the viruses—which they dubbed Pandoraviruses for the “Pandora’s box” of questions they open—last week (July 18) in Science.

“This is a major discovery that substantially expands the complexity of the giant viruses and confirms that viral diversity is still largely underexplored,” Christelle Desnues, a virologist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Marseilles, who was not involved in the study, told Nature.

The researchers, evolutionary biologists Jean-Michel Claverie and Chantal Abergel at Aix-Marseille University in France, have been part of the teams that first discovered the giant viruses in 2003. In 2011. Claverie and Abergel also helped identify and describe the giant virus Megavirus chilensis, the largest virus known until their most recent discoveries. The duo found one of the new viruses, Pandoravirus salinus, in a water sample also containing M. chilensis, which they collected off the Chilean coast. Under the ...