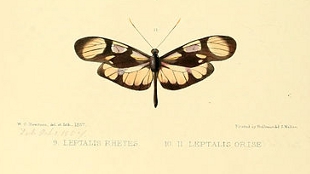

A male Leptalis orise, discoverd in the 1800sWikimedia, William Chapman HewitsonIt often takes researchers more than 2 decades to officially name and publish a description of a newly discovered species, according to a study published yesterday (November 20) in Current Biology. Because of this delay, some of the species may become extinct before they are officially cataloged—possibly throwing off estimates of extinction rates and biodiversity.

A male Leptalis orise, discoverd in the 1800sWikimedia, William Chapman HewitsonIt often takes researchers more than 2 decades to officially name and publish a description of a newly discovered species, according to a study published yesterday (November 20) in Current Biology. Because of this delay, some of the species may become extinct before they are officially cataloged—possibly throwing off estimates of extinction rates and biodiversity.

“Papers like this are good: they help us identify the bottlenecks in the process," Quentin Wheeler, at the International Institute for Species Exploration at Arizona State University told ScienceNOW.

Researchers from the National Museum of Natural History in Paris investigated the nearly 17,000 new species published in 2007 and picked 600 to analyze more closely. Surprisingly, the lag time for professional biologists averaged about 21 years with a median of 12 years, whereas it took only 15 years for the amateur collector. In addition, the time from discovery to publication was shorter for aquatic species, as well as in countries with a per capita income of less than $35,000.

The reason for the huge lag time is manifold. Once specimens are collected and brought back ...