The floral scent of blooming lavender, the leafy smell of freshly cut grass, and the earthy aroma of the first rain transport most people back to childhood summer memories. Cells called sensory olfactory neurons, located in the nasal cavity, enable people to experience these smells.

Brian Lin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, generated an in vitro system to study the cells that help preserve the sense of smell.

Brian Lin

Unlike neurons in the central nervous system, these cells regenerate throughout life to combat damage caused by infections like COVID-19, toxin exposure, or aging. However, a lack of accessible and robust culture models limited researchers’ understanding of this continuous neurogenesis and its decline in disease and aging.

To overcome this, Brian Lin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, and his team developed an organoid model of the adult mouse olfactory epithelium.1 They used this to identify the stem cell population crucial for adult neurogenesis, which is important for the sense of smell. Their results, published in Cell Reports Methods, offer an easy-to-use in vitro system to study the cellular players that influence olfaction in the nasal cavity and may guide the development of treatments for smell loss.

The inability to culture olfactory cells has been a challenge in the field, said Hiroaki Matsunami, a sensory biologist at Duke University, who was not associated with the study. “This paper tackles this problem by creating an organoid so that it [partially] mimics the in vivo environment. One of the selling points of this is that the procedure seems to be pretty simple compared to some other [methods],” he said.

Juliana Gutschow Gameiro, an olfactory biologist at the State University of Londrina, was an exchange student in Lin’s lab at Tufts University when she carried out experiments to generate mouse olfactory organoids.

Brian Lin

Previously, researchers had identified two multipotent stem cell populations within the olfactory epithelium that contribute to neurogenesis: Dormant horizontal basal cells (HBCs) become active after injury, while globose basal cells (GBCs) generate olfactory neurons in the undamaged epithelium.2 Lin and his team wanted to develop a system to study the regulation of these two populations.

“The actual beginning of the project was actually a mistake,” recalled Lin, because they ran out of ultra-low attachment 3D cell culture dishes: Standard methods involve growing organoids in full suspension. But the lead author Juliana Gutschow Gameiro, an olfactory biologist at the State University of Londrina, continued experiments with the dishes they had anyway. “It was the same aim, but the way that we got about it was completely by chance,” said Lin.

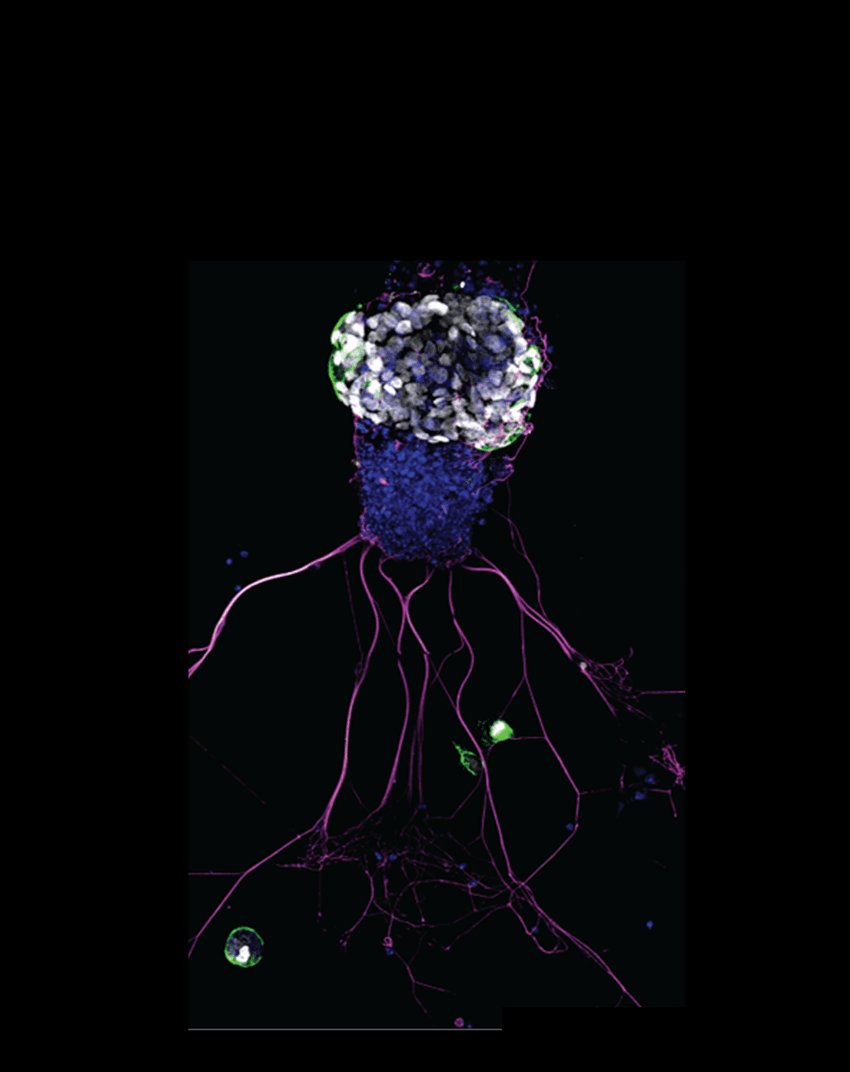

The researchers isolated olfactory cells from adult mice and cultured them with a cocktail of chemicals that induce neurogenesis.3 In about a week, the cells grew and attached to the bottom of the dishes, yielding a non-standard adherent 3D culture system. The researchers observed axon-like projections in these cell clumps, and immunostaining confirmed that the organoids contained olfactory sensory neurons. “We couldn't really believe it,” said Lin. “But when you see something like that, you recognize that those are neurons.”

A mouse olfactory organoid, with stem cell population (white), of which some are quiescent stem cells (green). Magenta color depicts neurons, and blue marks all cell nuclei.

Juliana Gutschow Gameiro

RNA sequencing revealed that the organoids contained several cell types, including HBCs and GBCs. To investigate these, the researchers mapped their fate in the organoids. While HBCs remained unchanged and did not develop into neuronal cells, their selective depletion impaired the formation of new neurons, suggesting that the cells, once thought to be quiescent, are necessary for olfactory neurogenesis.

Although Lin did not expect a neurogenic role of HBCs, he was not entirely surprised. “Whenever somebody mentions a professional or quiescent stem cell population, you have to wonder what they do on a normal day-to-day basis,” he said. “Their day job can't just be sitting there.”

Matsunami agreed. “It's not too surprising that one cell type is supporting the other cell type,” he said. “However, defining which cell type supports which…is an important question.”

Predictive algorithms to determine how HBCs interact with GBCs suggested that the cells form a bidirectional niche that supports adult neurogenesis through signaling pathways like Notch, Wnt, and neuregulin. According to Lin, identifying the factors that GBCs and HBCs use to communicate and maintain neurogenesis could point towards therapeutics for the loss of smell in the future.

While the system is useful for dissecting developmental stages of olfactory epithelium, Matsunami noted that it lacked mature olfactory sensory neuron populations, limiting its usefulness to study those cells. “There is clearly room for improvement if the goal is to really recreate the epithelium that mimics the real nose,” he added.

Lin said the team is refining their methodology to better recapitulate human olfactory epithelium. He added that the organoids are rich in neurons but lack the glial cells supporting them. “We don't have that diversity, [but] we would love to be able to recapitulate that.”

- Gameiro JG, et al. Quiescent horizontal basal stem cells act as a niche for olfactory neurogenesis in a mouse 3D organoid model. Cell Rep Methods. 2025;5(6):101055.

- Schwob JE, et al. Stem and progenitor cells of the mammalian olfactory epithelium: Taking poietic license. J Comp Neurol. 2017;525(4):1034-1054.

- Ren W, et al. Expansion of murine and human olfactory epithelium/mucosa colonies and generation of mature olfactory sensory neurons under chemically defined conditions. Theranostics. 2021;11(2):684-699.