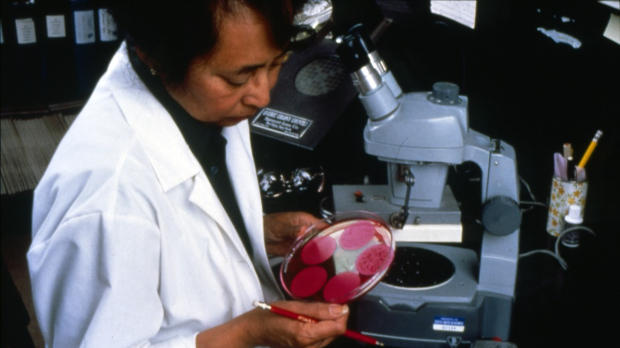

WIKIMEDIA, SEATTLE MUNICIPAL ARCHIVESLife science is dominated by white men. A 2014 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges found that men make up 62 percent of full-time medical school faculty, and the National Science Foundation found that white people (men and women) made up 71 percent of the science and engineering workforce in 2013. While the skewed numbers are obvious and persistent, the reasons for these disparities are less clear.

WIKIMEDIA, SEATTLE MUNICIPAL ARCHIVESLife science is dominated by white men. A 2014 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges found that men make up 62 percent of full-time medical school faculty, and the National Science Foundation found that white people (men and women) made up 71 percent of the science and engineering workforce in 2013. While the skewed numbers are obvious and persistent, the reasons for these disparities are less clear.

Two new studies aim to root out biases in funding decisions at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), but they come to somewhat different conclusions.

The first, an analysis of reviewers comments on R01 applications submitted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison between 2010 and 2014, found that while women were more likely to be praised than men in reviews of their R01 renewal applications, female applicants scored an average of four points lower than their male counterparts. “Even though we think we’re being objective, the truth is we grew up in a society where there are gender stereotypes, and they unconsciously impact our assessments of people,” Anne Wright, a medical anthropologist at the University of Arizona who wasn’t involved in the study, told ...