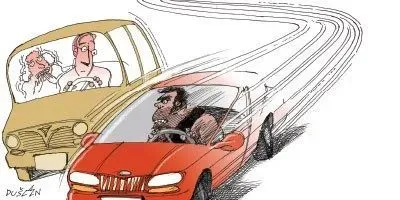

© DUSAN PETRICIC We live in a much different world from that in which we evolved. Until very recently, survival for all humans was difficult. Harsh conditions fostered cooperation within small groups, often made up mostly of one’s relatives, thus favoring strong social bonds. Over the last few centuries, and especially in the last few decades, however, the invention of rapid communication systems that span vast distances and a flood of affordable commercial conveniences allow us to interact with a huge number of people over our lifetimes, but those interactions are typically much more cursory. Even though our rational, educated minds can adapt to different environments, our basic hardwired instincts are slower to evolve. Biologically, the human brain that went to the Moon is the same that hunted mammoths in the last Ice Age. And tribal instincts, emotions, and attitudes—crucial for our ancestors’ survival and reproduction since they first roamed the African savannah—still influence many of our decisions and actions today, often in detrimental ways.

© DUSAN PETRICIC We live in a much different world from that in which we evolved. Until very recently, survival for all humans was difficult. Harsh conditions fostered cooperation within small groups, often made up mostly of one’s relatives, thus favoring strong social bonds. Over the last few centuries, and especially in the last few decades, however, the invention of rapid communication systems that span vast distances and a flood of affordable commercial conveniences allow us to interact with a huge number of people over our lifetimes, but those interactions are typically much more cursory. Even though our rational, educated minds can adapt to different environments, our basic hardwired instincts are slower to evolve. Biologically, the human brain that went to the Moon is the same that hunted mammoths in the last Ice Age. And tribal instincts, emotions, and attitudes—crucial for our ancestors’ survival and reproduction since they first roamed the African savannah—still influence many of our decisions and actions today, often in detrimental ways.

For ancient humans, being accepted into the tribe was essential for survival; interactions with strangers were rare. Every social interaction could therefore have important consequences for one’s role in the tribe, and this tribal structure instilled a rigid social hierarchy. An innate respect for such hierarchy, which can manifest as obedience to authority figures, was demonstrated by the classic experiments of Stanley Milgram. When participants were instructed by a scientist to administer electric shocks to another person (an accomplice of the scientist), 65 percent fully complied, even though they had been led to believe the shocks were up to 450 volts and extremely painful (J Abnorm Soc Psychol, 67:371-78, 1963). Scientists have also shown that we tend to vote for political candidates who are taller ...