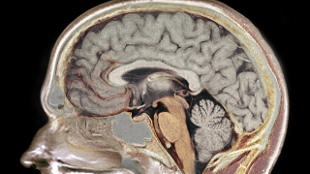

WIKIMEDIA, GARPENHOLMOn April 2nd, 2013, President Obama proposed a forward-thinking, $100 million research program designed to unlock the mysteries of the human brain. The BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative seeks to identify how brain cells and neural circuits interact in order to inform the development of future treatments for brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, and traumatic brain injury.

WIKIMEDIA, GARPENHOLMOn April 2nd, 2013, President Obama proposed a forward-thinking, $100 million research program designed to unlock the mysteries of the human brain. The BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative seeks to identify how brain cells and neural circuits interact in order to inform the development of future treatments for brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, and traumatic brain injury.

This Initiative could favorably contribute to medical practice years from now. It should not, however, overshadow the potential of neurogenomic advances to improve the diagnosis, treatment and management of neurological disorders right now.

Most of my career has focused on neurogenomics. During the Human Genome Project era, I managed a clinical neurogenomics program at the National Institutes of Health to further understanding the genetic underpinnings of neurological disorders to help diagnose, treat, cure, and even prevent disease. Today, I oversee the development of neurodiagnostics for the neurology business of Quest Diagnostics, with an emphasis on rare neurological disorders, autism, and dementias.

Over the years, I’ve come to identify certain obstacles that prevent the translation of neurogenomic science into effective clinical management. These obstacles are surmountable, ...