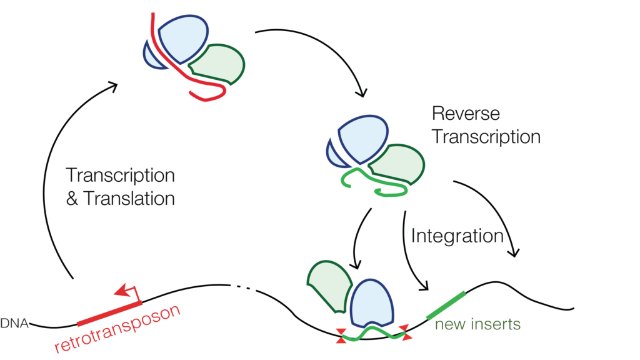

WIKIMEDIA, MARIUSWALTERTo protect their genes from being wrecked by retrotransposons, or jumping genes, mouse cells usually employ histone methylation to stop these rogue genetic elements from being transcribed. But how does the genome stay protected in the pre-implantation embryo, when methyl groups are temporarily stripped from cells’ DNA. A new study, published yesterday (June 29) in Cell, finds tRNA fragments are key.

WIKIMEDIA, MARIUSWALTERTo protect their genes from being wrecked by retrotransposons, or jumping genes, mouse cells usually employ histone methylation to stop these rogue genetic elements from being transcribed. But how does the genome stay protected in the pre-implantation embryo, when methyl groups are temporarily stripped from cells’ DNA. A new study, published yesterday (June 29) in Cell, finds tRNA fragments are key.

Based on previous studies in fruit flies, Andrea Schorn and Rob Martienssen of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory thought the answer to what protects vulnerable mouse embryo genomes might lie in small RNAs. To find them, they made some tweaks to the usual techniques. As they explain in their paper, “many small RNA sequencing studies omit RNA fragments shorter than 19 [nucleotides] or discard sequencing reads that map to multiple loci in the genome, thus often discarding reads matching young, potentially active transposons…”

By including smaller fragments in their RNA library and analysis, the authors turned up “very abundant” 18- and 22-nucleotide fragments of tRNAs. Results of further experiments suggested the 18-nucleotide fragments occupy the retrotransposons’ primer binding sites, blocking full tRNA molecules from binding there ...