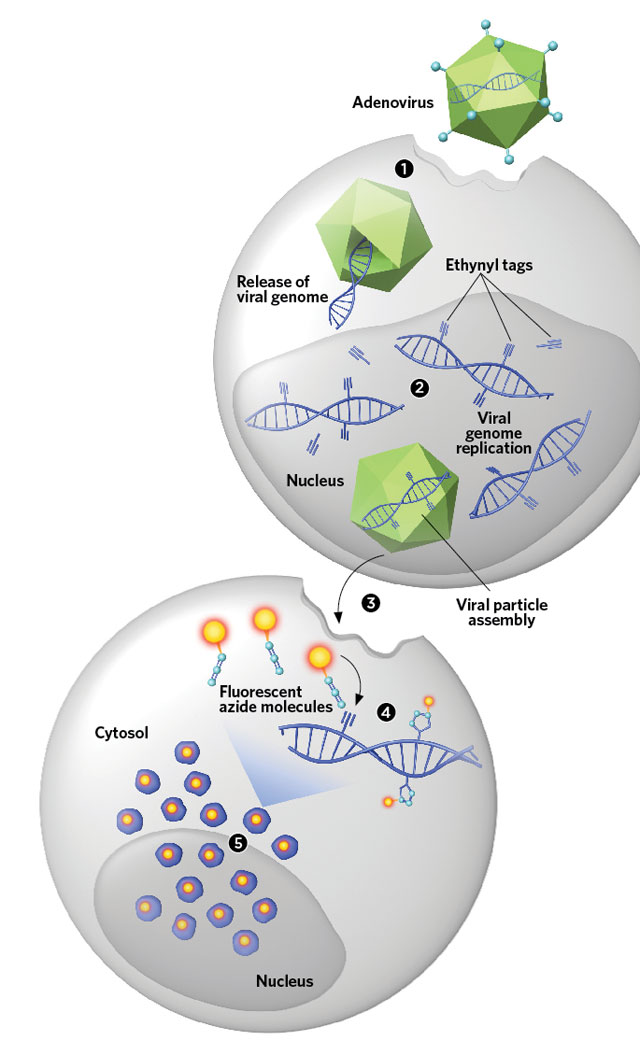

TAG AND TRACK: An adenovirus infects a cell (1). The viral DNA then incorporates ethynyl-tagged nucleosides during replication (2). The tagged virus is harvested and infected into another cell (3). After the virus sheds its outer coat, fluorescent azide molecules bind to the ethynyls (4), offering a way to visually track individual viral genomes in the cytosol and nucleus (5). © GEORGE RETSECKObserving viruses infecting cells is essential for making plans to defeat them, but the two main methods for viewing viral DNA in host cells have limitations.

TAG AND TRACK: An adenovirus infects a cell (1). The viral DNA then incorporates ethynyl-tagged nucleosides during replication (2). The tagged virus is harvested and infected into another cell (3). After the virus sheds its outer coat, fluorescent azide molecules bind to the ethynyls (4), offering a way to visually track individual viral genomes in the cytosol and nucleus (5). © GEORGE RETSECKObserving viruses infecting cells is essential for making plans to defeat them, but the two main methods for viewing viral DNA in host cells have limitations.

Genetically engineering the virus to contain sequences that can be bound by fluorescent proteins may interfere with the structure and behavior of the viral DNA, says Urs Greber, a virologist at the University of Zurich. And with the other popular technique, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), “one is never sure if every [viral] DNA in the cell is equally accessible” for labeling, he says, adding that the harsh denaturing and permeabilizing conditions required for FISH may also destroy or remove viral DNA.

So Greber and his colleagues have developed a technique that avoids denaturation and modifies the viral genomes in a manner compatible with continued replication and viability. They use ethynyl-tagged versions of nucleotide precursors called nucleosides, which are incorporated into viral genomes during replication. ...