In 1991, a group of scientists gathered at Blanes, a Spanish town bordering the Mediterranean Sea, for a workshop conducted by The Hydrozoan Society.

A major focus of discussion at the meeting was jellyfish, specifically a phenomenon called ontogeny reversal. Researchers, including attendee Volker Schmid, a reputed marine scientist at the University of Basel, had observed that a few jellyfish species are capable of reverse development before they reach sexual maturity: They can reactivate genetic programs specific to earlier life cycle stages.

But the workshop participants were in for a surprise: An announcement about researchers Giorgio Bavestrello and Christian Sommer’s discovery of a species of “immortal” jellyfish quickly became the main topic of discussion.1 These sexually mature adult jellyfish could return to the juvenile state if stressed, instead of producing gametes and dying.

“That was astonishing, because this was a kind of counter evidence against the fundamental dogma of biology that lives go in one direction, from fertilization of the eggs to death,” said marine zoologist Stefano Piraino, now at the University of Salento, who attended the workshop at the time. This breakthrough was “made just by chance,” recalled Piraino.

Discovery of the Immortal Jellyfish: Turritopsis dohrnii

It all began the 1980s, when Bavestrello, at the University of Genoa, and Sommer, at Ruhr University Bochum, collected jellyfish later classified as Turritopsis dohrnii, hoping to rear the animals for their research.2 These transparent jellyfish with a bright, red stomach are about half the size of a person’s pinky nail. They begin their lives as tiny, free-swimming planula larvae, which settle down on sea floors or ship hulls to form a colony of polyps. These later bud into mobile, jellyfish-like forms called medusae. As medusae mature, they spawn sperm and eggs, which fertilize to produce planula larvae.

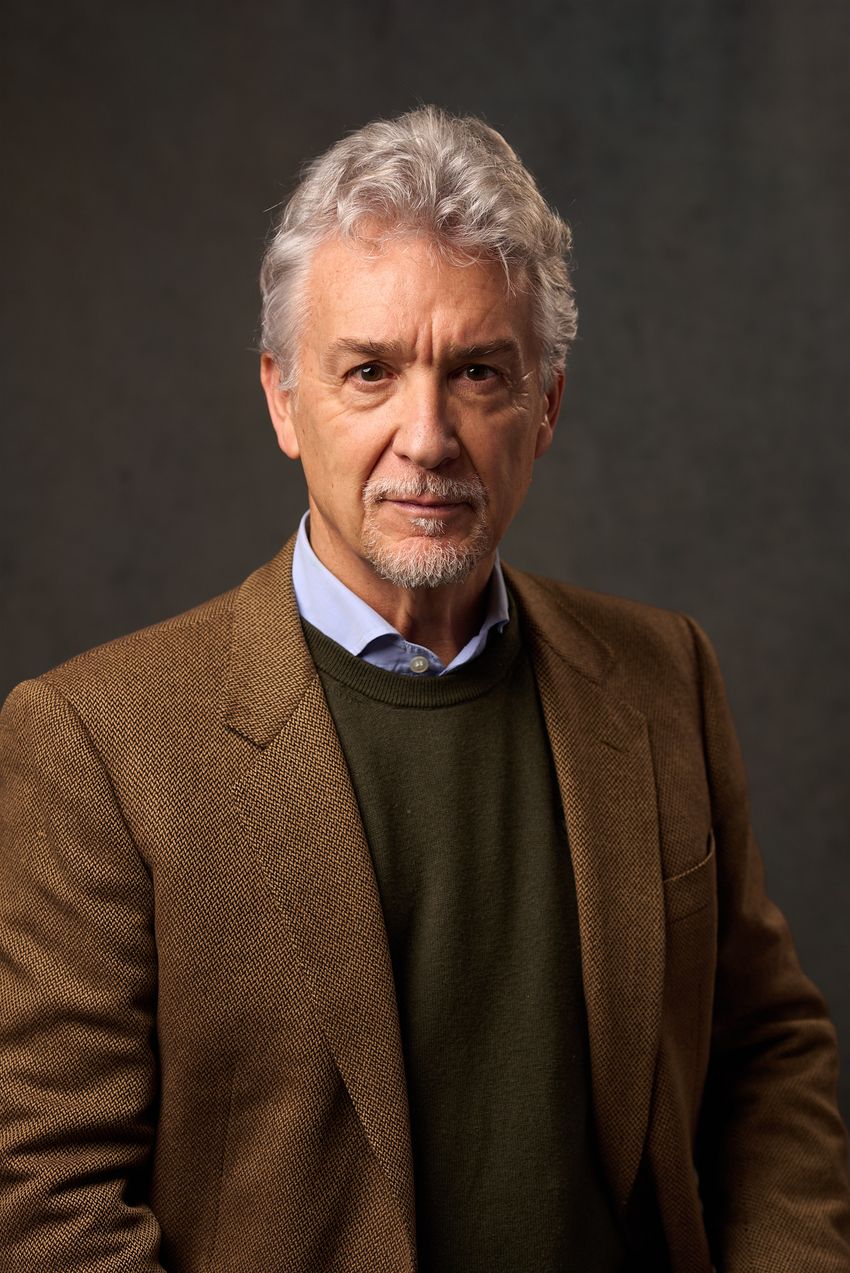

Stefano Piraino, a marine zoologist at University of Salento, helped understand the cells and genes involved in T. dohrnii’s ontogeny reversal.

Stefano Piraino

Bavestrello and Sommer collected and reared T. dohrnii polyps, which eventually released medusae. Incidentally, the researchers forgot about the creatures over the weekend. When they checked on the jellyfish next, they observed several polyps settled at the bottom of the rearing jar. Puzzled, they continued observing the animals and eventually found that stressful conditions triggered the medusae to turn into a ball of tissue called cysts, which fell to the bottom of the jar. The cysts then transformed into polyps without releasing gametes that would fertilize to form the larvae.

This was the first evidence of an organism reverting from a sexually mature stage to a juvenile stage without producing gametes and dying. This was so strange, that “it might be comparable to a butterfly that would be able to revert to the caterpillar stage,” said Piraino.

When the researchers presented these findings in the workshop in Blanes, Schmid said it was impossible. To put the doubts to rest, Piraino and other workshop participants dove into the ocean, collected T. dohrnii, and repeated the experiment. Consistent with the initial observation, stressed medusae fell to the bottom of a bowl and produced polyps. Finally convinced about the phenomenon, Schmid and Piraino collaborated to study the cellular mechanism behind T. dohrnii’s ontogeny reversal.

Over time, scientists found that the animals can undergo this process of reverse development multiple times, helping them achieve biological immortality, a state where animals do not die of old age.3 Researchers realized they could study the unusual rejuvenation capability of these immortal jellyfish to better understand aging and improve regenerative medicine. In the last few years, scientists have characterized the T. dohrnii genome in order to pinpoint the genetic and molecular mechanisms behind this property of the jellyfish.

Are Immortal Jellyfish Actually Immortal?

Schmid and Piraino first investigated the cell population in the jellyfish that contribute to its transformation from the medusa to the polyp stage. They excised different tissues in the medusae and stressed the animals by starving them, changing the water temperature or salinity, or clamping them with forceps.

They observed that only medusae with an intact outer layer and portions of their circulatory canal system could revert to polyps. Electron microscopy and patterns of DNA replication indicated that this process involved transdifferentiation: Fully differentiated cells in these tissues changed their commitment to transform into cells of another lineage.4 “This was certainly a point of interest for the media, because they claimed that we had discovered the elixir of immortality,” recalled Piraino. But the enthusiasm eventually waned for a decade, until another discovery put T. dohrnii back on the map.

Turritopsis dohrnii is the only known animal species wherein adults can undergo reverse development under stress to avoid aging and death.

Maria Pascual-Torner

In the 2000s, Maria Pia Miglietta routinely travelled across the globe to study hydrozoans for her graduate studies at Duke University. As a side project, she would collect T. dohrnii, which she had grown up playing with back home on the Italian coast. Over time, she realized that the organism, which was first discovered in the Mediterranean Sea, had spread all across the world’s oceans, in waters off Spain, Italy, Japan, Southeast US, and Panama.

Miglietta suspected that this silent invasion took place when the jellyfish voyaged on ships and survived the long journeys in hostile waters due to their biological immortality.5 A media frenzy about the widespread immortal animals soon followed. “[This] got the attention of everybody. ‘Immortality, invasion, invasive capabilities’ were all buzz words, and made everybody crazy about the species. It was insane,” said Miglietta, now a marine biologist at Texas A&M University at Galveston.

But are the jellyfish really immortal? Piraino clarified: No, they are not. Although T. dohrnii individuals do not die of old age, making them “biologically immortal,” they can still succumb to predation or disease, indicating that they are not truly immortal. “If a single species would be able to achieve immortality and continuously reproduce, that species would invade the planet until it would fill the oceans,” said Piraino.

Maria Pia Miglietta, a marine biologist at Texas A&M University at Galveston, studies the genomics of T. dohrnii to better understand its ontogeny reversal.

Maria Pia Miglietta

Nonetheless, researchers remain interested in these animals because they can provide important insights about aging and rejuvenation. “If evolution can select for animals that don't age, then, in theory, at least, we could use technology to extend our longevity and prevent aging and its associated diseases,” said Joao Pedro Magalhaes, a molecular biogerontologist at the University of Birmingham. “More futuristically, you can even think about gene therapies. If you find genes of interest in this long-lived species, maybe we can use them to do genetic engineering that will prevent human diseases.”

The Genes Behind the Immortal Jellyfish’s Life Cycle Reversal

María Pascual-Torner, a marine scientist at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Barcelona does just that in her research. Together with Carlos López-Otín at the University of Oviedo, she investigated how the genome of the immortal jellyfish differed from that of other jellyfish belonging to the same genus.

For their study, Pascual-Torner traveled with a colleague to the Italian coast to collect the animals in 2019. They traveled along the shore in a camper van complete with a stereo microscope to observe their samples, diving into the Mediterranean Sea to gather T. dohrnii polyps. These eventually transformed into medusae, from which the researchers isolated DNA to obtain the genome sequence.

'Immortality, invasion, invasive capabilities’ were all buzz words, and made everybody crazy about the species.

—Maria Pia Miglietta, Texas A&M University at Galveston

Pascual-Torner and her team compared the genome of T. dohrnii with that of another jellyfish species, Turritopsis rubra, that does not show biological immortality.6 “We [paid] attention to some genes, some 1,000 genes, that are related to the aging process,” said Pascual-Torner.

T. dohrnii had variants and more copies of genes encoding DNA repair proteins and DNA polymerases, suggesting enhanced replicative capabilities. They also found that compared to T. rubra, T. dohrnii carried more copies of some genes associated with oxidative stress response, hinting that the animal could protect its genome from reactive oxygen species-induced damage, contributing to better genome stability. Additionally, T. dohrnii carried potentially protective variants in genes involved in maintenance of telomeres, the protective caps at chromosome ends that shorten as an organism ages, causing senescence.

“But this is just like the first step,” said Pascual-Torner. “This study and this species can help understand aging, for sure, but there's many things to keep studying.”

Miglietta agreed, but added the two jellyfish species are not as closely related, and a better comparison would be with a more closely-related species or the same organism through different life stages.

Maria Pascual-Torner, a marine scientist at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Barcelona, investigated differences between the genomes of the immortal jellyfish and another related jellyfish species.

Maria Pascual-Torner

Previously, in a collaboration with Piraino, Miglietta compared the gene expression profiles of T. dohrnii when they were medusae, polyps, as well as cysts.7 “I wanted to try isolate what is unique to the cyst,” said Miglietta, because the cyst gets rearranged to become a new polyp instead of dying.

The researchers observed that compared to medusae and polyps, cysts expressed lower levels of genes associated with cell differentiation, cell fate determination, and organ development and patterning. This suggested that the suppression of these processes could contribute to T. dohrnii’s reverse development and transdifferentiation. In contrast, cysts had upregulated expression of DNA repair- and telomere maintenance-related genes, indicating that regulation of genomic integrity may play a significant role in the regenerative events occurring during that stage.

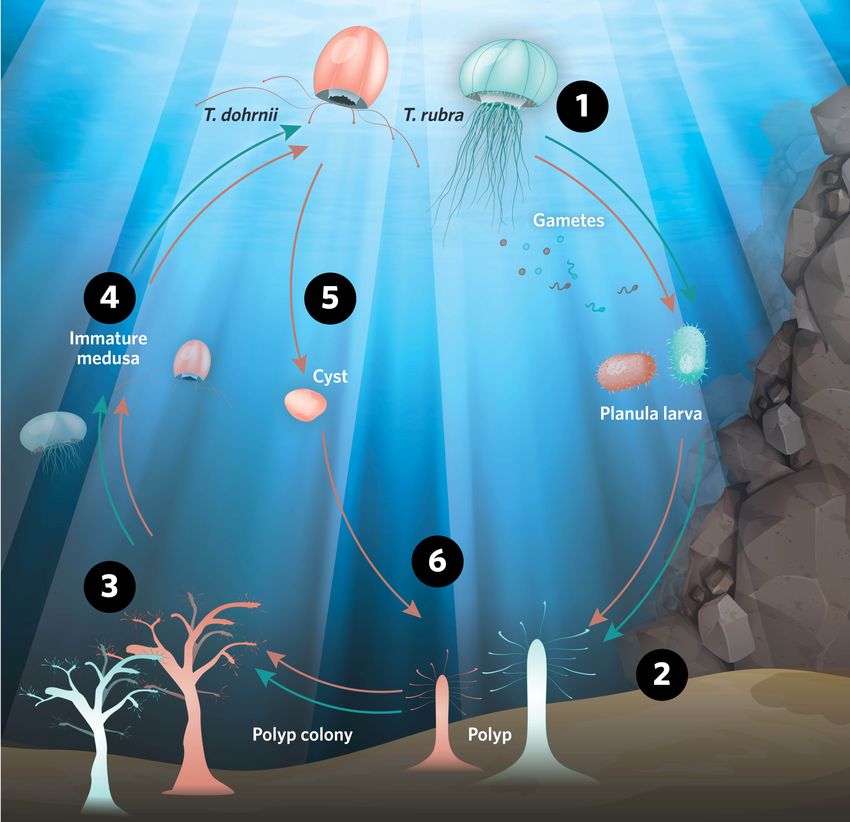

The Immortal Jellyfish Life Cycle ExplainedStressed Turritopsis dohrnii adults undergo reverse development to the larval stage, helping them avoid aging and death, and earning them the name “immortal” jellyfish.  modified from © istock.com, blueringmedia, ttsz, Magnilion; designed by erin lemieux 1) The first few stages are common for both species. Sexually mature jellyfish medusae spawn eggs and sperm, which fertilize to produce small larvae called planula. 2) Planula larvae settle on surfaces like ocean floor or ship hulls; they develop into polyps, which eventually form a colony. 3) Polyp colonies bud new jellyfish medusae. 4) Juvenile medusae feed on plankton and grow in size, becoming sexually mature in a few weeks. 5) In T. rubra, the next stage in the cycle is production of gametes to repeat the life cycle. This is where T. dohrnii’s life cycle bifurcates. When T. dohrnii adults become senescent, physically damaged, or stressed, they shrink and lose their ability to swim, transforming into balls of tissue called cysts. 6) In 24–36 hours, cysts settle on a surface and develop polyp-like features, which then form a colony. |

To her, it made sense that the DNA was protected. “We accumulate mutations spontaneously, and then we repair some mutations, and then some mutations remain,” said Miglietta. “If you are immortal, then there must be something in place to prevent [mutations from] accumulating, because eventually they're going to be deleterious.”

When Pascual-Torner and her team carried out a similar comparison, they observed overexpression of some pluripotency targets in the cyst stage, indicating the cells’ ability to differentiate into various types of cells.

Can T. dohrnii Jellyfish Unlock the Secret of Immortality?

Mature cells becoming pluripotent and giving rise to different cell lineages is not exclusive to marine creatures. In Nobel Prize-winning work, Shinya Yamanaka found that the addition of four factors induced reprogramming in differentiated mouse skin cells, transforming them into an embryonic-like pluripotent state.8 Subsequently, researchers found that such induced pluripotent stem cells can give rise to every other mammalian cell type including neurons, heart, pancreatic, and liver cells, holding promise in the field of regenerative medicine.

Maria Pascual-Torner and a colleague collected T. dohrnii polyps in the Mediterranean Sea.

Maria Pascual-Torner

However, this in vitro system with mammalian cells cultured in a Petri dish may not accurately represent how cells behave within an organ. Mammalian cells are complex, making it challenging to study them within an organ. “Turritopsis would offer the possibility to investigate what happens to rejuvenating cells in vivo,” said Piraino. Miglietta agreed and added, “And then we can apply the knowledge to other system.”

Pascual-Torner and Miglietta acknowledged that advancements in sequencing technologies are increasingly allowing them to ask more questions. “The field is evolving at a speed that is incredible and really opens up some questions that you would [have] never [dreamt of] answering before, and now you can,” said Miglietta, who hopes that researchers will soon be able to edit T. dohrnii genes to carry out functional studies.

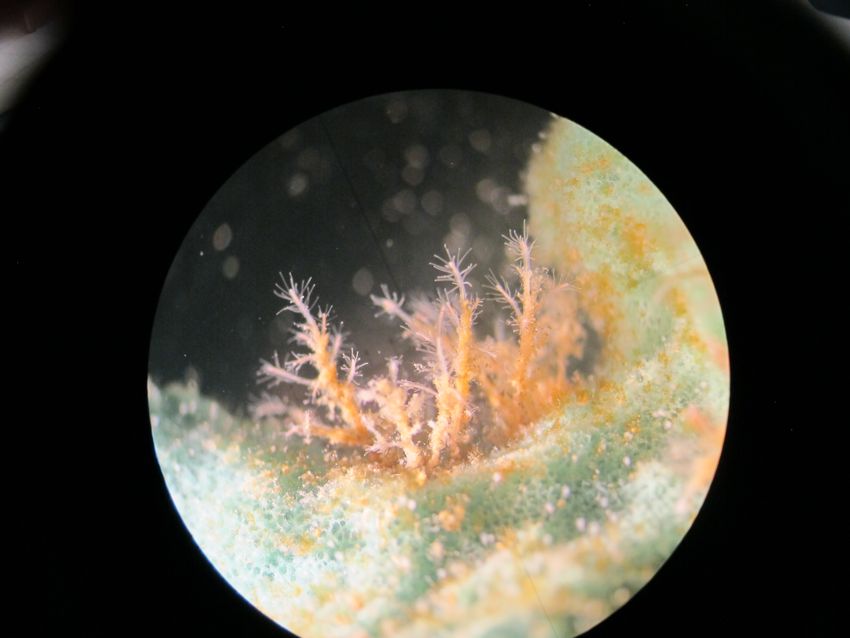

A small polyp colony of Turritopsis dohrnii. In the warmer months of the year, each polyp will bud 4-5 small medusae, which will eventually grow up to the adult (sexually competent) stage.

Stefano Piraino

Pascual-Torner and her colleagues investigated the functional implication of one such variant they identified in the protection of telomeres protein 1 (POT1) protein in T. dohrnii. POT1 binds to telomeres, resulting in the inhibition of telomerase, a telomere-protecting enzyme. The variant in T. dohrnii POT1 reduced its binding to telomere nucleotides, which would decrease telomerase inhibition. When they introduced a similar variation in recombinant human POT1, they observed reduced binding to telomere nucleotides, validating that the T. dohrnii variant could potentially improve telomere maintenance by reducing the inhibition of telomerase. Even as researchers await gene editing tools in T. dohrnii, they have continued investigating on other lines. “We're looking at genes that are typically generally known to be involved in aging and lifespan in other organisms, like in mammals,” said Miglietta. “And we wanted to know their behavior in Turritopsis dohrnii.”

Early data have hinted that the jellyfish cysts express increased levels of genes like those from the sirtuin family, which are linked with a healthy lifespan in humans.9 They also observed that T. dohrnii expressed higher levels of genes that are known to regulate telomere length in humans. Moreover, jellyfish cysts had active heat shock proteins, the deficit of which contributes to aging in mammals. “So, we kind of further have evidence of some genes that are important for humans and important for mammals have a role in the rejuvenation of this animal,” said Miglietta.

Although T. dohrnii is a promising system to study rejuvenation, some challenges remain. According to Piraino, researchers should focus on solving problems related to culturing the animals and editing their genes. Until such a time arrives, he noted the importance of investing more funds and increasing efforts to investigate marine biodiversity. “[This] may be rewarded unexpectedly, like with discoveries or organisms with unexpected capacity like reverse ontogeny,” he said. “And there might be much more to discover.”

- Bavestrello G, et al. Bi-directional conversion in Turritopsis nutricula (Hydrozoa). Sci Mar. 1992; 56(2-3):137-140.

- Miglietta MP, et al. Species in the genus Turritopsis (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa): A molecular evaluation. J Zool Syst Evol Res. 2007;45(1):11-19

- Lisenkova AA, et al. Complete mitochondrial genome and evolutionary analysis of Turritopsis dohrnii, the "immortal" jellyfish with a reversible life-cycle. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;107:232-238.

- Piraino S, et al. Reversing the life cycle: Medusae transforming into polyps and cell transdifferentiation in Turritopsis nutricula (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa). Biol Bull. 1996;190(3):302-312.

- Miglietta MP, Lessios HA. A silent invasion. Biol Invasions. 2008;11(4):825-834.

- Pascual-Torner M, et al. Comparative genomics of mortal and immortal cnidarians unveils novel keys behind rejuvenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(36):e2118763119.

- Matsumoto Y, et al. Transcriptome characterization of reverse development in Turritopsis dohrnii (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria). G3. 2019;9(12):4127-4138.

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663-676.

- Matsumoto Y, Miglietta MP. The genetic networks of regeneration, cell plasticity, and longevity of the Immortal Jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa). bioRxiv. 2025.07.02.660568