RIKEN BRAIN SCIENCE INSTITUTE, PER NILSSONPathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) include the aggregation of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides inside neurons and the accumulation of extracellular Aβ plaques. Previously, the mechanisms by which Aβ leaves neurons were unknown, and it has been controversial whether the intracellular or extracellular accumulation of Aβ plays a larger role in AD-associated symptoms. A paper published today (October 3) in Cell Reports shows that Aβ leaves neurons in an autophagy-dependent manner, and suggests that aggregation of intracellular Aβ contributes to AD pathology.

RIKEN BRAIN SCIENCE INSTITUTE, PER NILSSONPathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) include the aggregation of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides inside neurons and the accumulation of extracellular Aβ plaques. Previously, the mechanisms by which Aβ leaves neurons were unknown, and it has been controversial whether the intracellular or extracellular accumulation of Aβ plays a larger role in AD-associated symptoms. A paper published today (October 3) in Cell Reports shows that Aβ leaves neurons in an autophagy-dependent manner, and suggests that aggregation of intracellular Aβ contributes to AD pathology.

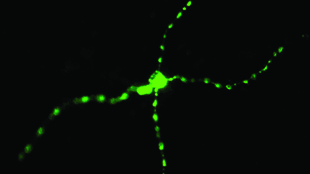

Per Nilsson, a research scientist at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Japan, along with his colleagues crossed mice deficient in autophagy in forebrain neurons with transgenic animals that produce abnormally high levels of the Aβ precursor protein. They found that the offspring had far fewer extracellular Aβ plaques than the transgenic mice that showed normal autophagy.

“We know that autophagy is the cleaning system within the cell,” said Nilsson. “Our expectation was that if we delete autophagy, we would get more of the Aβ plaques outside the cell. But we saw the contrary, so we were really surprised by that, and we had to work hard to understand why,” he continued. In order to understand the reason that autophagy-deficient mice had fewer Aβ plaques, ...