Newborn babies may appear peaceful, blinking at the bright new world, but their tiny guts teem with microscopic life. These microbes produce signals that train the infant immune system to recognize friend from foe. While scientists know that breastmilk supports immune development, they did not fully understand the molecules that guide microbe-mediated immune imprinting, which shapes long-term immunological outcomes.1

Katherine Donald, a microbiologist in Brett Finlay’s lab at the University of British Columbia studies how milk affects infant gut microbiota and immune maturation.

Katherine Donald

Recently, scientists found that an antibody in maternal milk, immunoglobulin A (IgA), prevents an infant gut bacterium, Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum, from inducing allergy-promoting immune responses.2 The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, uncover key players in immune development, paving the way for improved allergy prevention strategies in infants.

“[The results] show a substantial role for milk IgA in infant gut microbiota maturation,” said Katherine Donald, a microbiologist in Brett Finlay’s lab at the University of British Columbia and study coauthor. “Knowing that E. ramosum-specific IgA might help the infant during development could inform IgA additions to formula [milk].”

Meghan Koch, a maternal-offspring immunologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, who was not associated with the study, said, “This is really a nice study to try to tease out the intricacies [of IgA-microbiota interactions] and to basically support maybe future mechanistic studies.”

Donald and her team compared the amount of IgA in the breastmilk of 300 women from a previously established study cohort and the gut microbiome composition of their respective babies.3 They observed an inverse correlation between IgA levels and E. ramosum abundance, suggesting that the maternally derived antibody may limit this species in the infant gut.

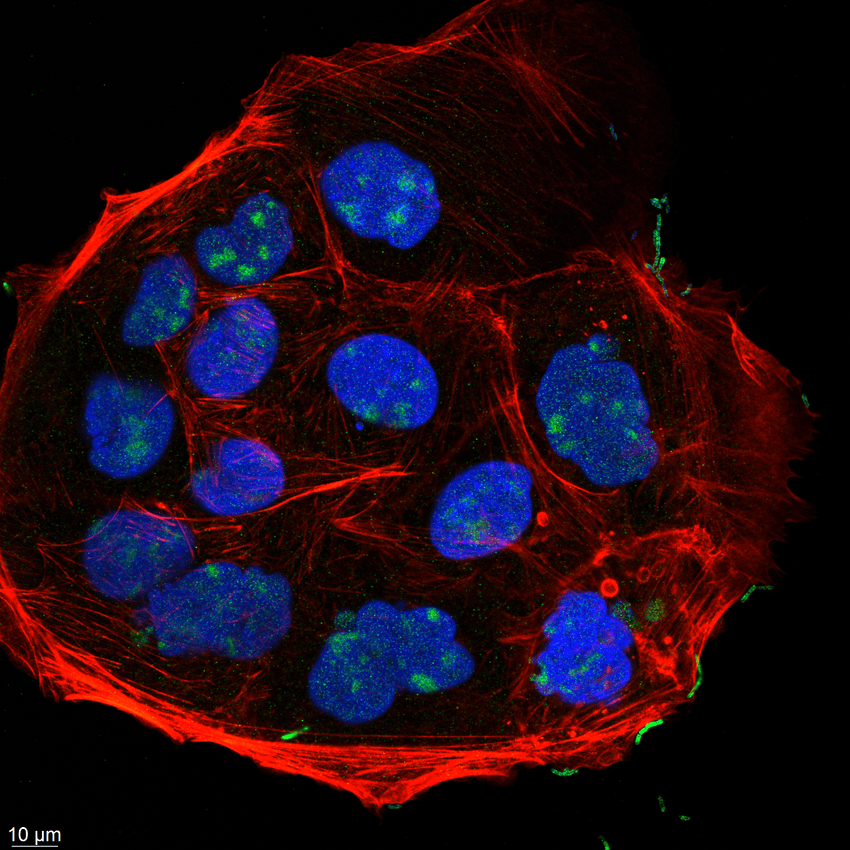

E. ramosum filaments (green) adhere to epithelial cells (nuclei stained blue, actin stained red) infected with the cultured bacterium.

Antonio Serapio-Palacios

IgA antibodies can control gut microbiota by preventing the attachment of some bacteria to the intestinal epithelium.4 To investigate whether milk IgA limited E. ramosum via a similar mechanism, Donald and her team exposed human-derived epithelial cell lines to the bacterium. Using immunofluorescence, the researchers observed that E. ramosum bound to the cells, leading to cytoskeletal rearrangement. However, bacteria incubated with IgA failed to attach to cultured epithelial cells, confirming that the antibodies prevent host-microbiota interaction.

RNA sequencing of E. ramosum-bound epithelial cells revealed upregulation of several genes involved in signaling pathways mediated by T helper 17 cells (Th17), which are implicated in allergies and some chronic diseases. However, antibody-treated bacteria failed to upregulate these genes in epithelial cells, indicating that E. ramosum triggers pathways involved in Th17-mediated inflammation in the gut and that milk IgA inhibits this effect.

Meghan Koch, an immunologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center studies how the mother may shape infant immunity.

Meghan Koch

While Donald expected that milk-derived IgA would influence the gut microbiota, “the specifics kind of surprised me,” she said. Researchers had previously found that the antibody helped the colonization of beneficial bacteria in the gut.5 “I was looking for good bacteria that IgA helped, but ended up finding this one, E. ramosum, that is actually limited by milk IgA,” said Donald.

Human milk is abundant in IgA, driving many studies about the antibody in mice, said Koch. “It's laudable for these investigators to try to take this to the next step, to say, ‘Okay, we can infer everything we want to from mice, but what actually happens in humans?’,” she said. “They did a good job of trying their in vitro model in several different cell lines,” she said, while noting that these may not accurately mimic physiological conditions.

“We couldn't get E. ramosum to colonize mice. We just have the cell culture work. But of course, in an organism, I'm sure it would be much different,” agreed Donald, adding that organoid systems could provide a clearer and more physiologically relevant picture.

Koch concurred, noting that organ-on-a-chip models of guts may help answer some questions. “As we get more invested in things like team science and increased flexibility and increased funding, those kinds of studies are possible,” said Koch, “which could really transform some of these findings by leaps and bounds.”

- Dawod B, et al. Breastfeeding and the developmental origins of mucosal immunity: How human milk shapes the innate and adaptive mucosal immune systems. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(6):547-556.

- Donald K, et al. Human milk IgA promotes normal immune development by limiting Th17-inducing Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum in the infant gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2025;122(28):e2501030122.

- Subbarao P, et al. The Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) study: Examining developmental origins of allergy and asthma. Thorax. 2015;70(10):998-1000.

- Bunker JJ, Bendelac A. IgA responses to microbiota. Immunity. 2018;49(2):211-224.

- Donald K, et al. Secretory IgA: Linking microbes, maternal health, and infant health through human milk. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30(5):650-659.