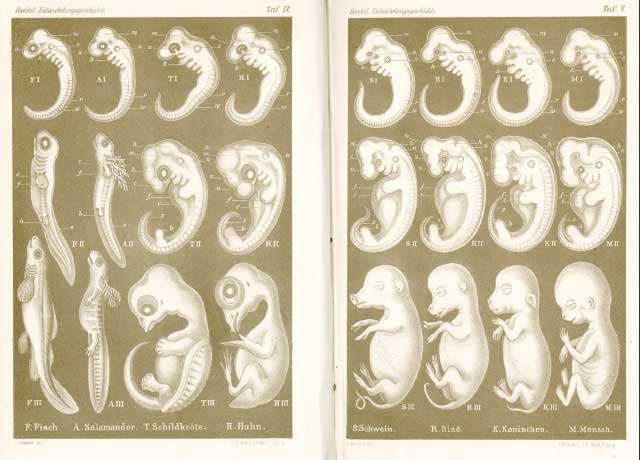

EMBRYONIC EVOLUTION: This comparative illustration of eight species’ embryos from Haeckel’s Anthropogenie (1874 edition) is among the most well-known of the German scientist’s images. The rows represent three developmental stages and the columns correspond to different species (fish, salamander, turtle, chicken, pig, cow, dog, and human). NICK HOPWOOD

EMBRYONIC EVOLUTION: This comparative illustration of eight species’ embryos from Haeckel’s Anthropogenie (1874 edition) is among the most well-known of the German scientist’s images. The rows represent three developmental stages and the columns correspond to different species (fish, salamander, turtle, chicken, pig, cow, dog, and human). NICK HOPWOOD

Ernst Haeckel, a biologist, artist, and philosopher born in Prussia in the 1830s, played a key role in spreading Darwinism in Germany. He was also deeply fascinated by embryology and illustrated some of the most remarkable comparisons of vertebrate embryos in his day. These images were widely printed and copied, both to argue for Haeckel’s controversial evolutionary theories and to debunk them.

Haeckel’s most influential idea was his now-infamous biogenetic law, summarized by the phrase “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”—in other words, an organism’s embryo progresses through stages of development that mirror its evolutionary history. According to this theory, embryos of more advanced species—humans, for example—would pass through stages in which they displayed the adult characteristics of their more primitive ancestors (such as fish gills or monkey ...