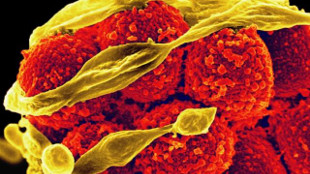

WIKIMEDIA, NIAID/NIHWhite blood cells, like neutrophils and macrophages, are well-known members of the team of that protects mammals from skin-invading pathogens. But a study published last week (January 2) in Science revealed that the body’s defense squad also includes a rather surprising member: fat. Not only do fat cells increase in number and size around the site of a skin infection, they also produce their very own antibiotic.

WIKIMEDIA, NIAID/NIHWhite blood cells, like neutrophils and macrophages, are well-known members of the team of that protects mammals from skin-invading pathogens. But a study published last week (January 2) in Science revealed that the body’s defense squad also includes a rather surprising member: fat. Not only do fat cells increase in number and size around the site of a skin infection, they also produce their very own antibiotic.

While white blood cells must first make their way to the site of infection, fat cells already in the area can react much faster, researchers from the University of California, San Diego Medical School have found. Richard Gallo and his colleagues injected mice with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), finding that the layer of fat around the injection site grew thicker because of increased numbers of fat cells, or adipocytes. Mice that couldn’t make new adipocytes were less able to combat MRSA infection than were control animals.

Surprisingly, the infection also triggered the fat cells to produce an antibiotic peptide called cathelicidin. “It was not known that adipocytes could produce antimicrobials, let alone that they make almost as much as a neutrophil,” Gallo said in a ...