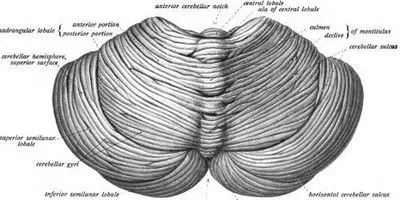

The cerebellumWIKIMEDIA, JOHANNES SOBOTTAExplosions during military combat can initially cause mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), which may lead to later development of neurodegenerative disorders like chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. What happens when the brain is exposed to blasts has been studied in both military veterans and animal models, yet how blast exposure-related TBI pathologies are connected to the changes observed in neuroimaging studies has not been well understood. According to a study published today (January 13) in Science Translational Medicine, cumulative blast exposure is associated with pronounced alterations in veterans’ brains—notably in the cerebellum, a finding the authors recapitulated in mouse models.

The cerebellumWIKIMEDIA, JOHANNES SOBOTTAExplosions during military combat can initially cause mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), which may lead to later development of neurodegenerative disorders like chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. What happens when the brain is exposed to blasts has been studied in both military veterans and animal models, yet how blast exposure-related TBI pathologies are connected to the changes observed in neuroimaging studies has not been well understood. According to a study published today (January 13) in Science Translational Medicine, cumulative blast exposure is associated with pronounced alterations in veterans’ brains—notably in the cerebellum, a finding the authors recapitulated in mouse models.

“It can be hard to accurately gauge the amount of blast exposure that soldiers have experienced because that information is self-reported in retrospective designs like the current study,” said Justin Karr, a graduate student in clinical neuropsychology who studies TBI at the University of Victoria in British Columbia and was not involved in the work. “The novelty of this study is linking the veterans’ brain imaging to the pathology in the blast-exposed animal model.”

Even without direct hits from fragmented objects or the force of a head-on collision, prior work has shown that a sudden shock wave of increased atmospheric pressure—called blast overpressure—alone can injure the brain. Researchers at Seattle’s VA Puget Sound Health Care System and University of Washington first examined a cohort of ...