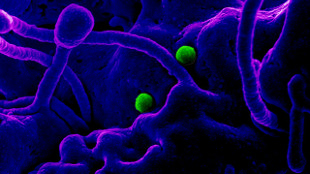

FLICKR, NIAID

FLICKR, NIAID

Until last month, outbreaks of Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) had been restricted to countries within the region for which the infectious disease was named. Since last month, there have now been more than 165 confirmed cases of MERS in South Korea, including 23 deaths, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). China, too, has confirmed one case stemming from the South Korean MERS outbreak. While a report coauthored by WHO and South Korean health officials released last week (June 13) suggested that the rate of new cases in the country was declining, it will be several weeks before investigators can tell whether the outbreak is truly under control.

“It’s a very complex outbreak,” said Peter Embarek, the WHO’s lead specialist on the MERS coronavirus ...