Bioinformatician Alejandra Medina-Rivera is proving that small cohorts can still yield big questions. From her lab at the International Laboratory for Human Genome Research at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, she co-leads the MexOMICS consortium, an initiative building patient registries across the country. Using data from just a few thousand participants, the team investigates how genetic and environmental factors interact in disorders such as lupus and Parkinson’s disease. They also collaborate closely with patient communities to address the questions that matter most to them.

Medina-Rivera had previously faced the challenge of studying small populations as a postdoctoral fellow at the SickKids Research Institute. There, she and her colleagues integrated functional genomics data to uncover how genes are regulated in the cells lining the inside of veins. By analyzing the genotypes of a few hundred individuals from five multigenerational French-Canadian families, they traced the roots of coagulation disorders through their DNA.1,2 To overcome the limited statistical power of such a small cohort, the team prioritized genomic regions linked to tissue function.

Bioinformatician Alejandra Medina-Rivera co-leads the MexOMICS consortium from her lab at the International Laboratory for Human Genome Research at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where she explores how genes and environment shape disease.

Alejandra Manjarrez

The experience showed Medina-Rivera that even constrained data can offer meaningful insights. When she returned to Mexico, her home country, in 2015, she set out to adapt this strategy to the local research landscape, where limited funding often makes large-scale genome-wide association studies unfeasible. But even this focused approach of using functional genomics to study small cohorts proved challenging. Few labs had the necessary equipment, and accessing the limited, tiny available cohorts was not easy because researchers often hesitated to share their data, she recalled.

Medina-Rivera discussed these challenges with Miguel Rentería, a computational geneticist at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute. They brainstormed solutions and decided to focus on twin data, where researchers can estimate heritability through questionnaires without immediate DNA sequencing. “And, if you later get funding for sequencing, you don’t need 100,000 people to do statistics; a few thousand would be enough,” Medina-Rivera noted.

They assembled a team of experts in bioinformatics, psychology, neuroscience, and genetics. Together, the team developed surveys covering medical family history, sociodemographic information, personality traits, mental health, lifestyle, and cognitive performance, among other areas. By mid-2019, they officially launched the Mexican twin registry: TwinsMX.3

As TwinsMX moved forward, Medina-Rivera also felt the need to create something valuable for the Mexican population affected by autoimmune diseases. “Lupus is more prevalent in Mexico than in other places,” she said, noting that it primarily affects young women. To better support this community, her team launched the Mexican Lupus Registry (LupusRGMX).

Meanwhile, the scarcity of studies on Parkinson’s disease in Latin American populations—and the absence of a national epidemiological study in Mexico—motivated her team to create a third initiative. In 2021, they established the Mexican Parkinson’s Research Network (MEX-PD) to deepen understanding of the disease in Mexican patients.4

During a conversation among the four leaders of the registries, the scientists realized that they had effectively built a consortium, Medina-Rivera recalled. “We’ve found ways to set up registries in Mexico at very low cost and with minimal maintenance,” she said. They decided to name the consortium MexOMICS and have it focused on maintaining these three databases while aiming to include omics data.5 Today, TwinsMX, LupusRGMX, and MEX-PD have 4,476, 3,006, and 1,204 participants, respectively. Although only a small percentage of them have genomic data so far, the team plans to grow that number over time.

Analyses of the registries are beginning to yield results, some with direct impact on the affected communities. For instance, Medina-Rivera and her colleagues studied how lupus affects quality of life, using self-reported answers to a World Health Organization questionnaire that measures physical, psychological, and social health, among other factors.6 Patients with lupus scored significantly lower in these areas compared to healthy controls, especially those individuals with lower socioeconomic status or delayed diagnoses. In Mexico, the lupus patient community has already used this study to advocate for their rights, presenting it to policymakers in efforts to amend health laws and recognize lupus as a disabling condition, Medina-Rivera noted.

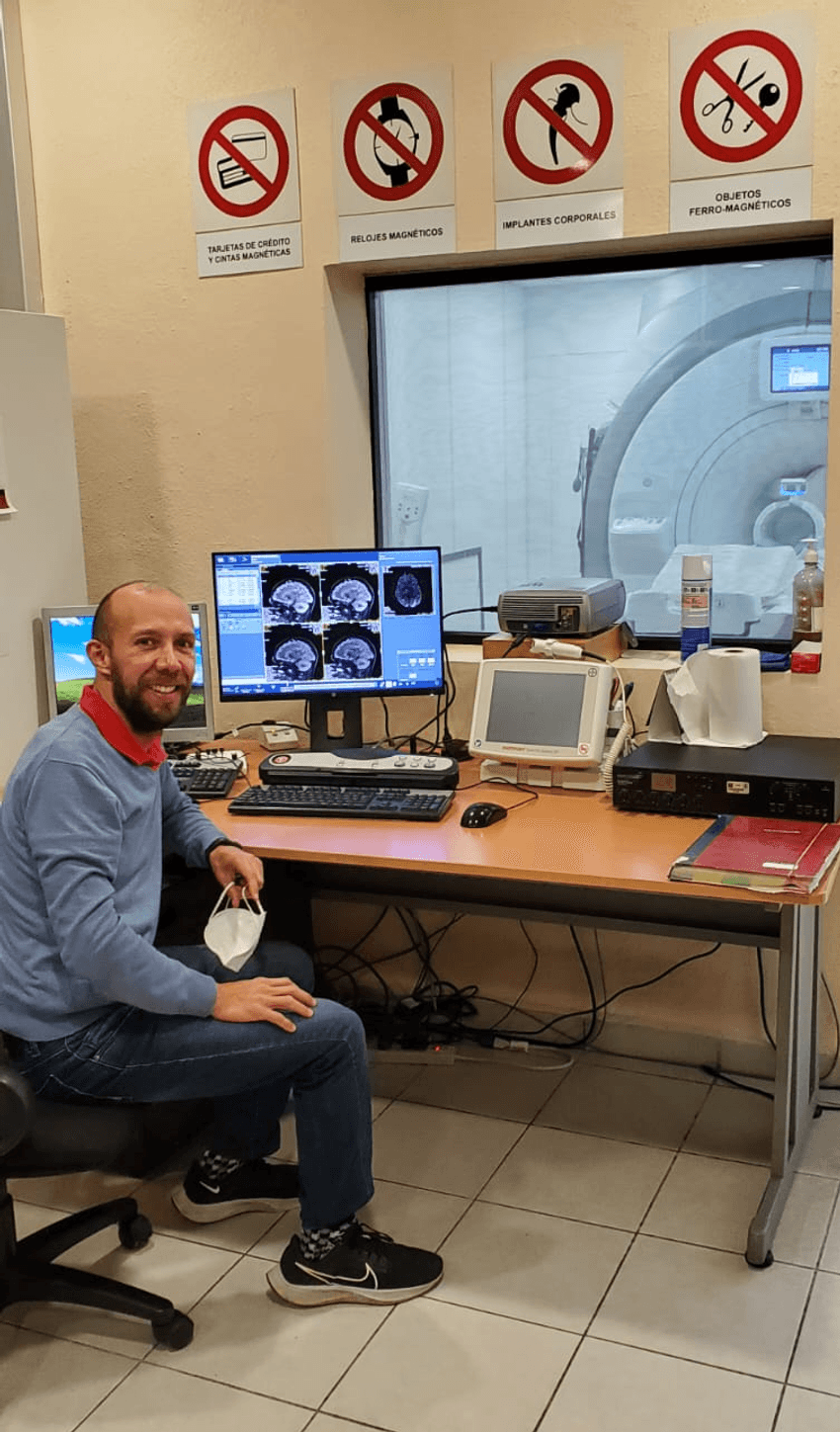

The MexOMICS team collects brain imaging data using MRI as part of their efforts. Domingo Martínez, a researcher in Medina-Rivera's group, conducts MRI scans of lupus patients.

RegGenoLab

Based on data from the three registries, the team is currently working on another analysis that explores the heritability of various gynecological health factors. Medina-Rivera expressed excitement about this project, given how little research focuses on women. “I believe it’s the largest study on women’s health ever conducted in the country,” she said.

Other patient communities in Mexico have approached the team to inquire about launching new registries. However, Medina-Rivera noted that building and maintaining registries like the existing three requires significant effort and close interaction with each community. For now, she considers it unlikely that her team will launch new registries, but they are eager to support anyone willing to take the lead on future initiatives. In the meantime, she and her colleagues remain focused on increasing participant numbers in their existing registries, expanding available data—such as DNA samples and MRI scans, which are still limited—and diving deeper into data analysis.

Although the main goal of these efforts is to better understand the Mexican population, Medina-Rivera highlighted the broader global significance of the data. “There are genetic variants that exist at different frequencies across populations, and while they will be relevant worldwide, they couldn’t be discovered using [only] samples from the Global North,” she said. She pointed to the discovery of a genetic variant enriched in the African American population that led to the development of cholesterol-lowering medications as an example.7

“Sometimes that focus is lost,” she added, but “if we study another population—even with a smaller [sample size]—the genetic variants with different frequencies could help us discover something new that could be applicable to everyone.”

Note: The interview with Medina-Rivera was conducted in Spanish.

- Dennis J, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in an intergenic chromosome 2q region associated with tissue factor pathway inhibitor plasma levels and venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(10):1960-1970.

- Dennis J, et al. Leveraging cell type specific regulatory regions to detect SNPs associated with tissue factor pathway inhibitor plasma levels. Genet Epidemiol. 2017;41(5):455-466.

- Leon-Apodaca AV, et al. TwinsMX: Uncovering the basis of health and disease in the Mexican population. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2019;22(6):611-616.

- Lázaro-Figueroa A, et al. MEX-PD: A national network for the epidemiological & genetic research of Parkinson’s disease. medRxiv. 2023.08.28.23294700.

- Reyes-Pérez P, et al. Building national patient registries in Mexico: Insights from the MexOMICS Consortium. Front Digit Health. 2024;6:1344103.

- Hernández-Ledesma AL, et al. Quality of life disparities among Mexican people with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLOS Digit Health. 2025;4(1):e0000706.

- Cohen J, et al. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet. 2005;37(2):161-165.