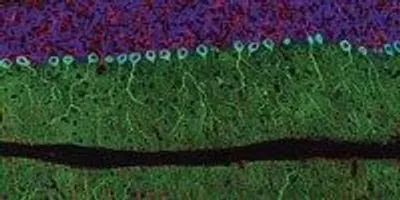

TOP NOTCH: Deerinck won first place in the 2002 Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition for this image of a rat cerebellum, captured using a confocal scope and fluorescent proteins. THOMAS J. DEERINCK/NIKON SMALL WORLD

TOP NOTCH: Deerinck won first place in the 2002 Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition for this image of a rat cerebellum, captured using a confocal scope and fluorescent proteins. THOMAS J. DEERINCK/NIKON SMALL WORLD

Last October, 40 stories high in 7 World Trade Center, Thomas Deerinck was among the first to check out the winners of the 2014 Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition, lined up around the perimeter of a room whose front windows looked out onto a panoramic view of New York City. It was the photo contest’s 40th anniversary, so the location was fitting. “It was pretty spectacular,” Deerinck recalls. A slide show of winning entries from the photo competition’s four decades featured one of his own works: a 2002 snapshot of a slice of rat cerebellum.

Deerinck has been a microscopist for nearly as long as Nikon has been running the Small World competition. He works at the National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR), ...