On the evening of February 7, 2025, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced a new policy that would reduce the agency’s funding for major research institutions nationwide. The move is estimated to slash four billion USD in funding coming from the NIH, sparking widespread concern and leaving many scientists uncertain about the future of their research.

“It came without a warning,” said Charles Hong, a physician-scientist at Michigan State University, who studies small molecules that modulate embryonic development using zebrafish.

Hong first heard the news on social media. “I thought it was just a rumor or a joke,” he said. The next morning, a university email confirmed the harsh reality of the cuts. “[The news] was demoralizing.”

The NIH plays a crucial role in supporting biomedical research. In 2024 alone, the agency provided at least $32 billion of funding for 60,000 grants in basic, translational, and clinical studies. This funding not only supported research but also fueled more than $92 billion in new economic activity and nearly half a million jobs, according a report from United for Medical Research. The proposed cuts could stall scientific progress, disrupting research operations and jeopardizing scientific careers.

What’s at Stake for Grant Funding?

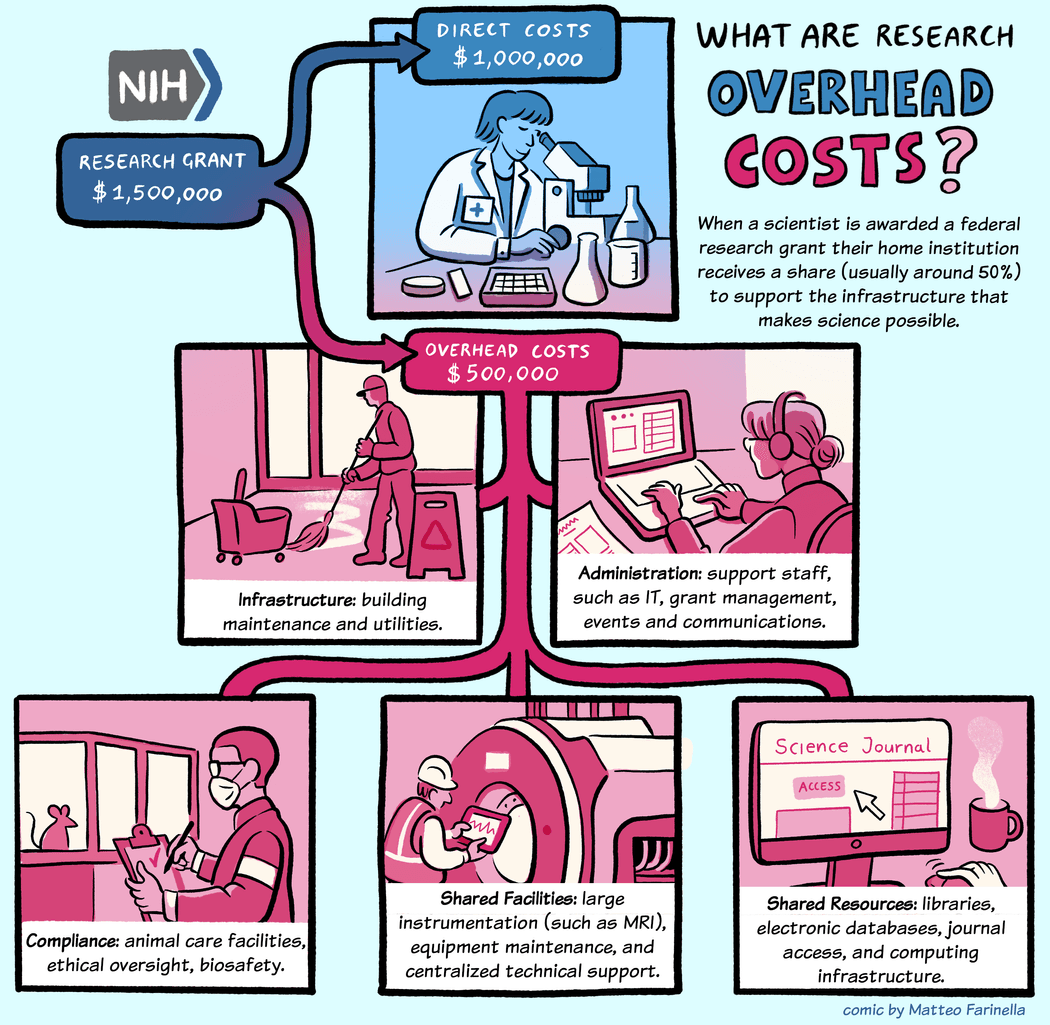

In the US research grant system, funding is split into two categories: direct and indirect costs. Direct funding supports the core aspects of a project, including scientist salaries, supplies, and equipment. The proposed policy, however, targets “indirect costs”—also known as facilities and administrative (F&A) costs—which fund essential resources such as infrastructure, administrative support, shared facilities, federal compliance for animal care, ethics, and biosafety, as well as access to electronic databases and journals.

For the past 70 years, the federal government and research institutions have maintained a partnership to support the infrastructure behind scientific research through F&A funding. On average, NIH indirect costs hover around 30 percent, with some institutions negotiating rates of over 50 percent. For instance, a researcher who receives a $1.5 million USD research grant receives one million for direct funding, while the remaining $500,000 is allocated to F&A costs to support their work. However, the new unilateral policy proposes capping these costs at just 15 percent—a drastic reduction from current levels.

“There was an agreement that [the federal government] will fund the infrastructure and all the behind-the-scenes stuff to allow these fundamental discoveries to happen,” said Hong. “I think [this policy] is very short-sighted and it will cripple our research enterprise.”

In response to the policy, the attorneys general of 22 states, along with a coalition of universities, swiftly filed a lawsuit on February 10. They argue that the NIH violated the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs how federal agencies develop and issue new regulations.

That same day, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order, preventing agencies from implementing, applying, or enforcing the new policy nationwide. The following hearing is set for February 21.

The new NIH policy aims to greatly reduce indirect funding of research institutions, which is critical in supporting research progress.

Matteo Farinella, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

How Will the New NIH Policy Affect Research?

Although the recent discussions about capping research funding focuses on budgetary details, David Perlmutter, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (WashU Medicine), who also serves as the dean of the medical school and has been funded by the NIH throughout his career, believes the conversation is missing a key point.

“We do research because we believe that we can improve people's lives through that research,” Perlmutter said. “The money that goes to [F&A costs] is essential to carrying out research and what we do with that is to set up things in a way so that many laboratories can benefit from the space and infrastructure.”

Hong remarked that the federal government aiding with F&A costs is an effective formula for keeping American research at the forefront. “The amazing thing about [scientists’] success, and the success of the NIH, is that for a fraction of money from the federal government, we’ve returned a lot in terms of discovery—[for example] CRISPR and induced pluripotent stem cells. These are all coming from scientists using [basic] fundamental research,” said Hong.

However, Perlmutter remarked that there is constant pressure to reduce F&A costs and emphasized that these negotiated F&A costs still do not fully cover the costs needed for research. He said, “Even though the NIH is a major funder compared to other funders of research, it's not enough money [by itself to develop] more cures or better treatments.” For instance, Perlmutter noted that last year WashU Medicine received $683 million in NIH funding, which included F&A costs, along with $167 million from private and other external sources. Despite this, the WashU Medicine contributed an additional $350 million of its own funds to sustain its research efforts, for total research funding of $1.2 billion.

If the proposed cap on F&A funding takes effect, universities and hospitals will need to reallocate their budgets to cover the shortfall, potentially forcing tough decisions about which research projects and clinical trials to sustain. Philanthropy and private foundations may offer some support, but Hong noted that these sources cannot fully replace federal funding. Perlmutter added that private donors are generally reluctant to fund administrative costs, putting institutions in a difficult position.

“Research is expensive, and good research is even more expensive,” Perlmutter said. In some cases, larger institutes may be able to dip into endowment funds. However, smaller institutions may really feel the pinch of funding cuts and struggle to sustain their research operations under the new policy. Another unintended consequence could be layoffs, as approximately 50 to 70 percent of F&A costs fund administrative personnel who support research but are not directly involved in it.

“It’s not [just] the academic pipeline that dries up. It’s going to be the biotechnology and biopharma pipelines that are also going to be affected,” said Hong. Many researchers trained at universities go into these industries and cutting the training grants and program opportunities will have an even bigger impact than a 15 percent cut now, Hong added.

The previous announcement of a potential freeze in grants and communication has caused widespread concern across the scientific community. As researchers monitor these funding developments, so do their trainees and students.

“I think the chill [of this proposed policy] will be felt immediately, but the impact is going to be lasting,” said Hong. “Then the real damage is going to be the next generation of people who are going to kind of avoid science after this.” Perlmutter echoed this concern, noting that many early-career investigators have already approached him with doubts about their future in research, asking, “Do you think I should change what I do?”

“We're concerned about people's careers. We're concerned about taking care of patients because we believe that our research can improve how we take care of patients,” Perlmutter said.

As the scientific community mobilizes to advocate for critical research funding, researchers, trainees, and institutions await the court’s decision on whether the proposed cuts will stand. The outcome will likely have significant implications for the future of biomedical research.