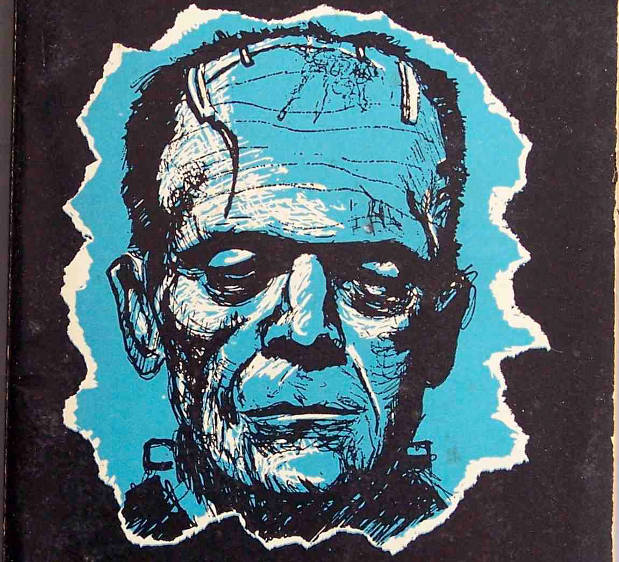

FLICKR, CHRIS DRUMMTwo centuries ago, during the dreary and bleak Mount Tambora volcanic winter of 1816, Mary Shelly began writing what would become her magnum opus, Frankenstein. No other work of fiction can claim to have such a lasting impact in articulating the public’s visceral fears of scientific and technological innovation. Indeed, the pejorative prefix Franken- has taken on a life of its own, attaching itself to many instances where innovation has outpaced our comfort zone, most prominently in the area genetically modified organisms (GMO)—also known as “Frankenfoods.”

FLICKR, CHRIS DRUMMTwo centuries ago, during the dreary and bleak Mount Tambora volcanic winter of 1816, Mary Shelly began writing what would become her magnum opus, Frankenstein. No other work of fiction can claim to have such a lasting impact in articulating the public’s visceral fears of scientific and technological innovation. Indeed, the pejorative prefix Franken- has taken on a life of its own, attaching itself to many instances where innovation has outpaced our comfort zone, most prominently in the area genetically modified organisms (GMO)—also known as “Frankenfoods.”

More often than not, however, this anti-GMO characterization does not echo scientific reality. GMO foodstuffs have been around for decades and are grown in both developed and developing countries around the world by millions of farmers on millions of acres of arable land. A number of genetically modified crops are currently commercially farmed in the U.S., including alfalfa, canola, corn, cotton, papaya, squash, and sugar beets. Typically these modified crops are engineered to have added benefits such as resistance and tolerance to many environmental stresses—herbicides, insects, drought, salinity, and lack of soil nutrients—or added enzymes or increased yields and nutrients. Many of these benefits provide solutions to real and urgent problems in our food supply, and the National Academies of Science have repeatedly found that ...