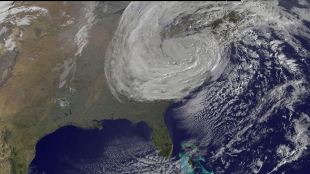

Satellite image of Hurrican SandyNOAA-NASA GOES ProjectSandy started as an ordinary hurricane, feeding on the warm surface waters of the Atlantic Ocean for fuel. The warm moist air spirals into the storm, and as moisture rains out, it provides the heat needed to drive the storm clouds. By the time Sandy made landfall on Monday evening, it had become an extratropical cyclone with some tropical storm characteristics: a lot of active thunderstorms but no eye. This transformation came about as a winter storm that had dumped snow in Colorado late last week merged with Sandy to form a hybrid storm that was also able to feed on the mid-latitude temperature contrasts. The resulting storm—double the size of a normal hurricane—spread hurricane force winds over a huge area of the United States as it made landfall. Meanwhile an extensive easterly wind fetch had already resulted in piled up sea waters along the Atlantic coast. This, in addition to the high tide, a favorable moon phase, and exceedingly low pressure, brought a record-setting storm surge that reached over 13 feet in lower Manhattan and coastal New Jersey. This perfect combination led to coastal erosion, massive flooding, and extensive wind damage that caused billions in dollars of damage.

Satellite image of Hurrican SandyNOAA-NASA GOES ProjectSandy started as an ordinary hurricane, feeding on the warm surface waters of the Atlantic Ocean for fuel. The warm moist air spirals into the storm, and as moisture rains out, it provides the heat needed to drive the storm clouds. By the time Sandy made landfall on Monday evening, it had become an extratropical cyclone with some tropical storm characteristics: a lot of active thunderstorms but no eye. This transformation came about as a winter storm that had dumped snow in Colorado late last week merged with Sandy to form a hybrid storm that was also able to feed on the mid-latitude temperature contrasts. The resulting storm—double the size of a normal hurricane—spread hurricane force winds over a huge area of the United States as it made landfall. Meanwhile an extensive easterly wind fetch had already resulted in piled up sea waters along the Atlantic coast. This, in addition to the high tide, a favorable moon phase, and exceedingly low pressure, brought a record-setting storm surge that reached over 13 feet in lower Manhattan and coastal New Jersey. This perfect combination led to coastal erosion, massive flooding, and extensive wind damage that caused billions in dollars of damage.

In many ways, Sandy resulted from the chance alignment of several factors associated with the weather. A human influence was also present, however. Storms typically reach out and grab available moisture from a region 3 to 5 times the rainfall radius of the storm itself, allowing it to make such prodigious amounts of rain. The sea surface temperatures just before the storm were some 5°F above the 30-year average, or “normal,” for this time of year over a 500 mile swath off the coastline from the Carolinas to Canada, and 1°F of this is very likely a direct result of global warming. With every degree F rise in temperatures, the atmosphere can hold 4 percent more moisture. Thus, Sandy was able to pull in more ...