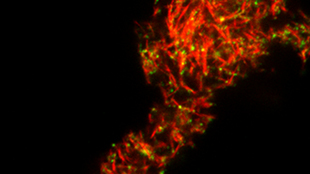

Red amyloid fibrils in semen and green HIV virus.NADIA ROAN/GLADSTONE INSTITUTES

Red amyloid fibrils in semen and green HIV virus.NADIA ROAN/GLADSTONE INSTITUTES

A protein found in semen makes HIV’s job of infecting immune cells easier, according to research published today in Cell Host & Microbe. The proteins, called semenogelins (SEMs), are abundant in semen and carry a positive charge that helps to bring the negatively-charged HIV virus and target immune cells together.

“The unique part of these studies is that they are actually identifying what can increase infection,” said Charu Kaushic, an immunologist at McMaster University who was not involved with the research. “Technically, it’s a very solid paper, but does this actually happen in the genital tract of women post-ejaculation? I’m not sure if it’s physiologically relevant.”

The research follows up on a 2007 study that identified a positively-charged seminal protein called SEVI (semen-derived enhancer of ...