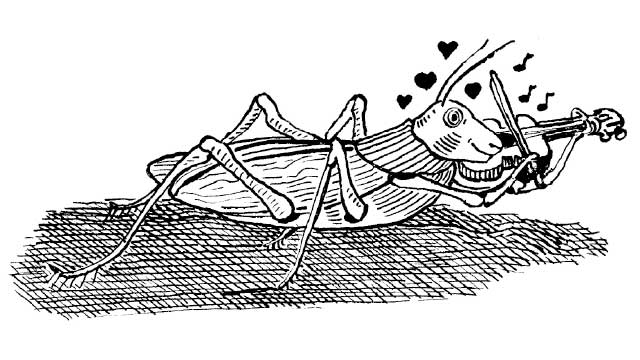

ANDRZEJ KRAUZEIn the wee hours of the morning earlier this year, my restless wife lay in bed and groaned: “That cricket must die. Now.” The amorous insect, perched very near our bedroom window, had been steadily chirping since sundown the previous evening. While well and good for his chances of securing a mate, the animal’s volubility was endangering the harmony of my own marital union.

ANDRZEJ KRAUZEIn the wee hours of the morning earlier this year, my restless wife lay in bed and groaned: “That cricket must die. Now.” The amorous insect, perched very near our bedroom window, had been steadily chirping since sundown the previous evening. While well and good for his chances of securing a mate, the animal’s volubility was endangering the harmony of my own marital union.

Nevertheless, we let him sing. And as I listened to the six-legged crooner, I was reminded that music is in the ear of the beholder. Or more precisely, in the beholder’s brain.

Thinkers have waxed poetic about the musical qualities of birdsong for centuries. “And hark! the Nightingale begins its song, / ‘Most musical, most melancholy’ bird!” wrote Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1798. A few decades later, Percy Bysshe Shelley celebrated the skylark: “Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert, / That from Heaven, or near it, / Pourest thy full heart / In profuse strains of unpremeditated art.”

Even Charles Darwin was guilty of romanticizing music in nature. “Musical notes and rhythm were first acquired by the male or female progenitors ...