SWIMMING LESSONS: Two differently angled light sources (red and blue) create shadows cast by a sperm moving across a photosensitive chip. Determining the distance between the center points of the shadows and their position relative to the light sources enables the sperm’s 3-D location to be calculated.GEORGE RETSECK

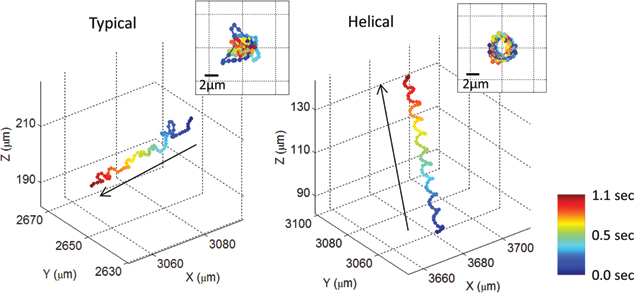

SWIMMING LESSONS: Two differently angled light sources (red and blue) create shadows cast by a sperm moving across a photosensitive chip. Determining the distance between the center points of the shadows and their position relative to the light sources enables the sperm’s 3-D location to be calculated.GEORGE RETSECK DIFFERENT STROKES: Using the tracking technique, researchers discovered that more than 90% of human sperm swim forward with small side-to-side movements, while approximately 5% swim in a faster-paced helical pattern. The remaining sperm swim in a hyper-activated or hyper-helical manner, where the sperm are more active but less directional.COURTESY OF AYDOGAN OZCAN WITH PERMISSION FROM PNAS 109:16018-22, 2012

DIFFERENT STROKES: Using the tracking technique, researchers discovered that more than 90% of human sperm swim forward with small side-to-side movements, while approximately 5% swim in a faster-paced helical pattern. The remaining sperm swim in a hyper-activated or hyper-helical manner, where the sperm are more active but less directional.COURTESY OF AYDOGAN OZCAN WITH PERMISSION FROM PNAS 109:16018-22, 2012

Human sperm are very tiny and swim very fast, which has made tracking their movements difficult. But now there is a solution—an unusual imaging system that not only doesn’t use a lens, it doesn’t even image sperm. Instead, it tracks their shadows.

Microscopes that use lenses have limited fields of view and depths of field, explains Aydogan Ozcan of the University of California, Los Angeles, who devised the new system. “That puts a limit on observing [sperm’s] natural three-dimensional trajectories,” he says.

His new system uses a photo sensor chip instead of a lens to increase the field of view, and tracks sperm’s shadows instead of the sperm themselves to increase depth of field. “Even if a sperm is moving up and down, you can ...