Studying an organ, even a rodent one, involves surveying millions of cells. To understand the biology of such complicated tissues, scientists adopt a puzzle approach, wherein they study small parts separately and then assemble the entire picture. This approach aided the creation of high-resolution atlases, such as those of the entire fruit fly brain and human cancers.1 Yet, evenly labeling single cells in intact organs is still a major challenge in the field.

Now, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have devised a new way to label proteins in millions of cells without compromising the tissue’s structure: continuous redispersion of volumetric equilibrium (CuRVE).2 The team implemented the technique in diverse animal tissues, demonstrating its adaptability. The approach, published in Nature Biotechnology, could enable scientists to easily study cell structure and function within tissues, without disrupting the original architecture and biological context.

Conventional protein-tagging methods, such as immunohistochemistry, rely on antibodies, but they struggle to penetrate through the entire tissue. The cells at the periphery encounter a different chemical concentration than those at the center, causing uneven protein labeling. “Imagine marinating a thick steak by simply dipping it in sauce. The outer layers absorb the marinade quickly and intensely, while the inner layers remain largely untouched unless the meat is soaked for an extended period,” said Kwanghun Chung, a chemical engineer and neuroscientist at MIT and author of the study, in a statement. “The challenge is even greater for protein labeling, as the chemicals we use for labeling are hundreds of times larger than those in marinades. As a result, it can take weeks for these molecules to diffuse into intact organs, making uniform chemical processing of organ-scale tissues virtually impossible and extremely slow.”

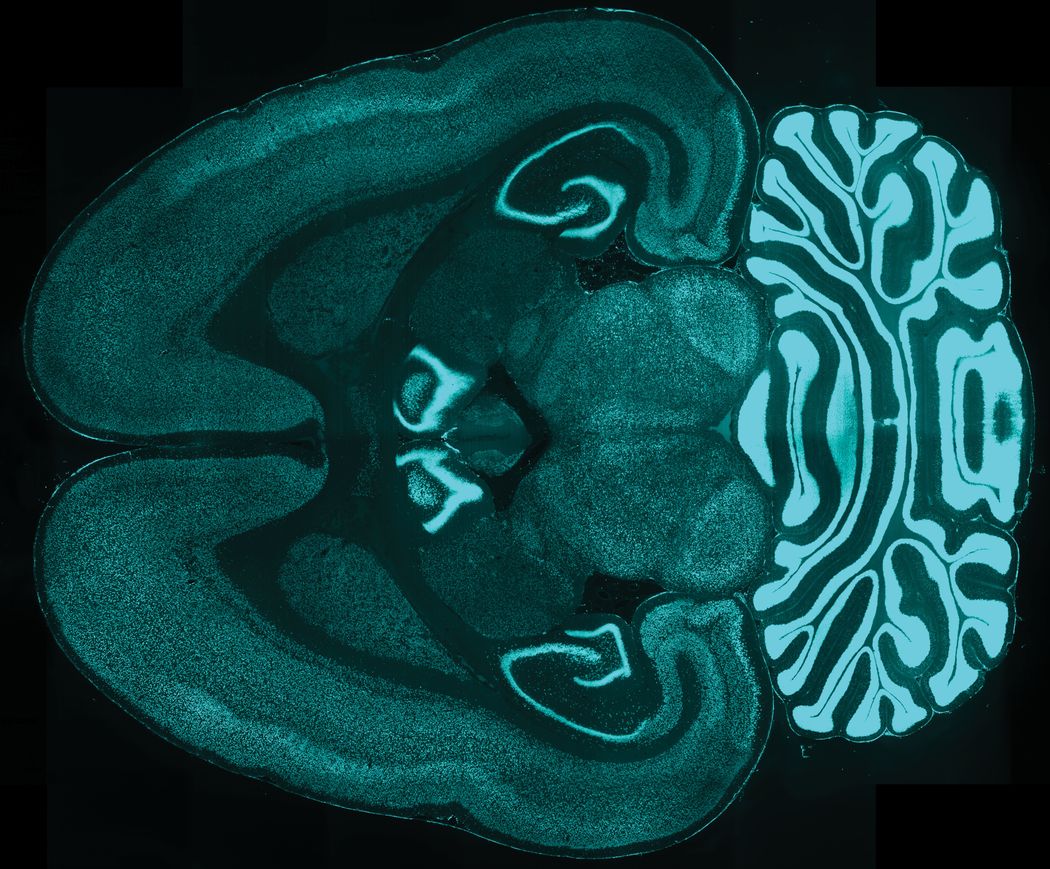

Improving antibody penetration allowed the researchers to label proteins in the interior and periphery of the tissue equally well. Shown here is an intact rat brain with all neurons labelled.

Chung Lab/MIT Picower Institute

To overcome this challenge, Chung and his colleagues developed CuRVE, wherein they maintained chemical equilibrium throughout the tissue by gradually modulating the speed of antibody-antigen binding. They combined this approach with stochastic electrotransport, a method that enhances the diffusion of molecules without damaging the tissue, to implement their electrophoretic-fast labeling using affinity sweeping in hydrogel (eFLASH) technique. A computational model comparing simple diffusion with eFLASH showed that eFLASH achieved a gradual and uniform concentration of antibody-antigen complexes throughout the tissue, while simple diffusion resulted in a gradated profile.

Next, the team tested the efficacy of the technique in biological tissue. In conventional protein labeling methods, the antibodies begin reacting with the antigen before fully permeating the tissue, thus getting rapidly consumed. To prevent this, the team modulated the speed of antibody binding using a detergent. They processed each hemisphere of an adult mouse brain either with or without antibody binding regulation, using the same amount of a neuronal antibody. In the hemisphere treated with eFLASH, they observed even labeling of neurons, whereas the other showed a gradated labeling pattern. With this approach, Chung and his team achieved uniform labeling of millions of cells in a single day. They also applied eFLASH to a variety of other tissue types—whole rat brain, marmoset brain block, human brain block, and mouse embryo, lung, and heart, among others—and observed similar results without additional optimization.

Lastly, the team wanted to compare their method to transgenic labeling, a technique commonly used to view single cells in intact tissues. However, the fluorescent marker used in this technique can be out of sync with the actual expression of the protein, since gene transcription is not always followed by protein production. When the team compared eFLASH with genetic labeling for cholinergic neurons and certain interneurons, they observed a significant mismatch, with eFLASH outperforming transgenic labeling. These findings emphasize the need to validate protein expression using varied approaches.

Chung hopes that this new and improved protein labeling method will power the creation of a repository of protein expression patterns in varied tissues. These will serve as a baseline to evaluate clinical tissue samples and for comparison with other labeling approaches.

- Dorkenwald S, et al. Neuronal wiring diagram of an adult brain. Nature. 2024;634(8032):124-138.

- Yun DH, et al. Uniform volumetric single-cell processing for organ-scale molecular phenotyping. Nat Biotechnol. 2025:1-12.