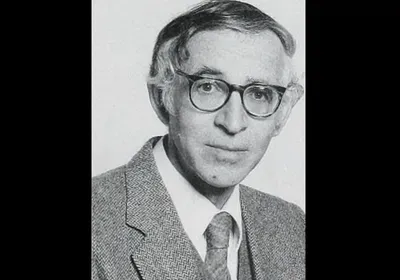

Aaron Klug, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982 for developing the technique of crystallographic electron microscopy and determining the structures of nucleic acid–protein complexes, died last Tuesday (November 20) at age 92, The Washington Post reports. His funeral is today (November 26), according to an obituary by the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, where Klug spent much of his career.

“Aaron Klug was a towering giant of 20th century molecular biology who made fundamental contributions to the development of methods to decipher and thus understand complex biological structures,” Venki Ramakrishnan, president of Britain’s Royal Society, says in a statement.

Klug was born in Zelvas, Lithuania, in 1926 but his family, fleeing anti-semitism, moved to South Africa when he was two years old. In 1945, he received his undergraduate degree from the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, where he studied physics, chemistry, and biology, according to ...