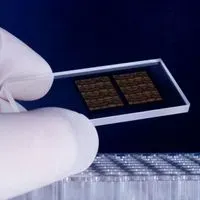

ABOVE: © ISTOCK.COM, DRA_SCHWARTZ

Chips used to detect single-nucleotide polymorphisms—the type of DNA microarrays used by direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies to detect variants in a person’s genome—have a false discovery rate of more than 85 percent when screening for very rare variants, according to a preprint published on bioRxiv on June 9.

Charleston Chiang, a human geneticist at the University of South California Keck School of Medicine who was not involved in the study, says he thinks the paper raises awareness of a potentially important problem in the direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing industry. Unreliable results may find their way to customers, who could “interpret the results at these rare variants literally, without accounting for any possible laboratory errors,” Chiang says. “That would be a legitimate concern.”

The chips tested in the study were supplied by the manufacturer Affymetrix, owned by Thermo Fisher Scientific. These specific chips are used by some ...