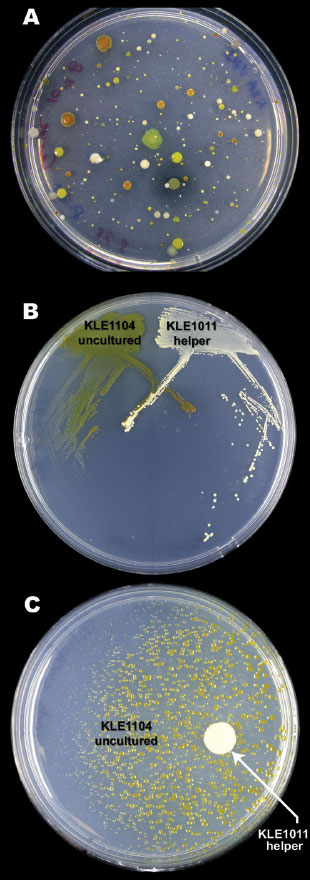

A HELPING HAND: To identify and cultivate bacteria whose growth depends on a soluble growth factor, Lewis plated bacteria from sand grains on agar (A) and isolated and streaked candidate pairs (B). The growth of KLE1104 (green) depends on KLE1011 (white), as its colonies get smaller the farther away they are from the helper cells (C). Used media from a helper strain culture is sufficient to support KLE1104 growth, indicating a growth factor is all that’s missing. A. D'ONOFRIO ET AL., CHEMISTRY & BIOLOGY, 17:254-64, 2010If you take a sample of seawater and plate it on a typical petri dish, colonies of bacteria will flourish. Each of those colonies springs from a single cell; counting those colonies provides an estimate of the number and variety of organisms in the water sample. But count the cells in that same sample directly, and you’ll find you’ve only scratched the surface.

A HELPING HAND: To identify and cultivate bacteria whose growth depends on a soluble growth factor, Lewis plated bacteria from sand grains on agar (A) and isolated and streaked candidate pairs (B). The growth of KLE1104 (green) depends on KLE1011 (white), as its colonies get smaller the farther away they are from the helper cells (C). Used media from a helper strain culture is sufficient to support KLE1104 growth, indicating a growth factor is all that’s missing. A. D'ONOFRIO ET AL., CHEMISTRY & BIOLOGY, 17:254-64, 2010If you take a sample of seawater and plate it on a typical petri dish, colonies of bacteria will flourish. Each of those colonies springs from a single cell; counting those colonies provides an estimate of the number and variety of organisms in the water sample. But count the cells in that same sample directly, and you’ll find you’ve only scratched the surface.

That difference is called “The Great Plate Count Anomaly,” and it is vast. By some estimates, direct cultivation captures just 0.01 percent to 1 percent of the bacterial diversity in biological samples. The rest represents a missed opportunity of sorts—organisms whose ecologic functions and metabolic potentials researchers could glimpse, perhaps by sequencing their DNA, but never directly study. This dark matter of the microbial world could be an untapped gold mine of antibiotics, biofuels, bioremediators, and more. (See “Lost Colonies,” The Scientist, October 2015.)

In the world of microbiology, such organisms are designated uncultivable. But that label isn’t quite right, says J. Cameron Thrash, a microbiologist at the Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge; after all, these organisms grow in nature, some exceptionally successfully. “I ...