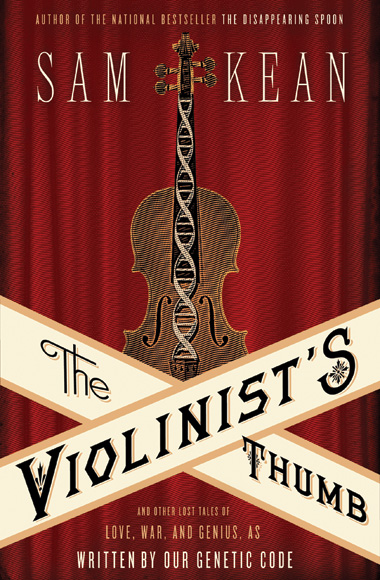

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY, JULY 2012

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY, JULY 2012

Chills and flames, frost and inferno, fire and ice. The two scientists who made the first great discoveries in genetics had a lot in common—not least the fact that both died obscure, mostly unmourned and happily forgotten by many. But whereas one’s legacy perished in fire, the other’s succumbed to ice.

The blaze came during the winter of 1884, at a monastery in what’s now the Czech Republic. A few friars spent one January day emptying out the office of their deceased abbot, Gregor Mendel, ruthlessly purging his files, consigning everything to a bonfire in the courtyard. Though a warm and capable man, Mendel had become something of an embarrassment to the monastery late in life, the cause for government inquiries, newspaper gossip, even a ...