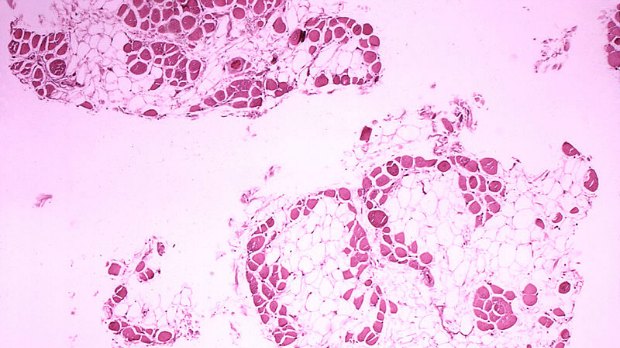

WIKIMEDIA, CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION'S PUBLIC HEALTH IMAGE LIBRARYCRISPR has fixed the protein problems in adult mice that lie at the root of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a progressive disease that saps kids of muscle strength and ultimately shortens their lives. Scientists had succeeded in using the gene-editing technique to restore protein function in human cells or mouse embryos, but this is the first time adult animals have been treated.

WIKIMEDIA, CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION'S PUBLIC HEALTH IMAGE LIBRARYCRISPR has fixed the protein problems in adult mice that lie at the root of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a progressive disease that saps kids of muscle strength and ultimately shortens their lives. Scientists had succeeded in using the gene-editing technique to restore protein function in human cells or mouse embryos, but this is the first time adult animals have been treated.

“The hope for gene editing is that if we do this right, we will only need to do one treatment,” Duke University’s Charlie Gersbach, who led one of three independent research teams that published results in Science last week (December 31), told The New York Times. “This method, if proven safe, could be applied to patients in the foreseeable future.”

The problematic protein is called dystrophin. All three groups took the same approach, first demonstrated in mouse embryos by Eric Olson of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in 2014, to correct dystrophin deficiencies. They clipped a mutant exon from the gene for dystrophin, resulting in a truncated but functional protein. “Importantly, in principle, the same strategy can be applied to numerous types of ...