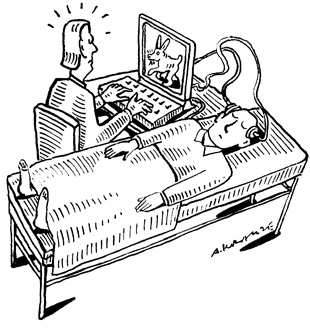

ANDRZEJ KRAUZE“[I was] somewhere, in a place like a studio to make a TV program or something,” a groggy study participant recounted (in Japanese). “A male person ran with short steps from the left side to the right side. Then, he tumbled.” The participant had recently been awoken by Masako Tamaki, a postdoc in the lab of neuroscientist Yukiyasu Kamitani of the ATR Computational Neuroscience Laboratories in Kyoto, Japan. He was lying in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner, doing his best to recall what he had been dreaming about. “He stumbled over something, and stood up while laughing, and said something,” the participant continued. “He said something to persons on the left side.”

ANDRZEJ KRAUZE“[I was] somewhere, in a place like a studio to make a TV program or something,” a groggy study participant recounted (in Japanese). “A male person ran with short steps from the left side to the right side. Then, he tumbled.” The participant had recently been awoken by Masako Tamaki, a postdoc in the lab of neuroscientist Yukiyasu Kamitani of the ATR Computational Neuroscience Laboratories in Kyoto, Japan. He was lying in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner, doing his best to recall what he had been dreaming about. “He stumbled over something, and stood up while laughing, and said something,” the participant continued. “He said something to persons on the left side.”

At first blush, the story doesn’t seem particularly informative. But the study subject saw a man, not a woman. And he was inside some sort of workplace. That fragmented information is enough for Kamitani and his team, who recorded dream appearances of 20 key objects, such as “male” or “room,” and used a machine-learning algorithm to correlate those concepts with the fMRI images to find patterns that could be used to predict what people were dreaming about without having to wake them. Such information could help inform the study of why people dream, an elusive question in neurobiology, Kamitani says. “Knowing what is represented during sleep would help to understand the function of dreaming.”

Knowing what is represented during sleep would help to understand the ...