About 50 percent of pregnancies fail, and one of the main reasons is aneuploidy, a genetic condition in which cells do not have the correct number of chromosomes.1 Aneuploidy commonly arises when chromosomes segregate improperly during meiosis, particularly in the genetically female parent.2

Rajiv McCoy, an evolutionary geneticist at Johns Hopkins University, wondered if specific genetic variants in the maternal genome are associated with the production of aneuploid embryos.

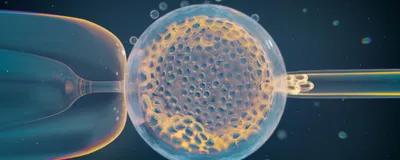

By studying in vitro fertilized (IVF) embryos prior to implantation, McCoy and his team recently linked specific variants of several meiotic genes, as well as their physical locations on chromosomes, that contribute to maternal aneuploidy.3 Their findings, published in Nature, reveal previously unknown molecular details of the phenomenon, which may inform future efforts towards a clinical intervention for pregnancy loss.

“It is a great paper,” said Patricia Hunt, a molecular biologist at Washington State University who was not involved in the work. Hunt expects that the study “will be widely cited and provide new directions of investigation for those in the field.”

For genetically female individuals, meiosis starts prenatally. Homologous chromosomes— one from each parent—in oocytes, which are egg cell progenitors, pair and recombine during fetal development. The chromosome pairs stay lined up in this precarious configuration for decades and do not segregate until the individuals begin ovulating monthly during puberty.

In contrast, for genetically male individuals, meiosis begins at puberty and happens continually throughout their lives. Unlike oocytes, spermatocytes, which are the sperm cell progenitors, do not have to pause between critical steps in meiosis. Many researchers think that this difference is why aneuploidy arises more commonly in the egg than in the sperm; it is also why aneuploidy risk significantly increases in advanced maternal age.

Rajiv McCoy, an evolutionary geneticist at Johns Hopkins University, uses computational methods to understand the genomic factors that shape development.

Rajiv McCoy

To trace the parental origin of aneuploidy, McCoy and his colleagues compared DNA from over 150,000 IVF embryos to that from nearly 25,000 pairs of biological parents. Then, they performed genetic and computational analyses on the samples.

The researchers found that indeed, aneuploidy mostly arose maternally. Maternal aneuploidy was nearly 10 times more common than its paternal counterpart, and its rate accelerated proportionally with age. They also discovered that meiotic crossover, a process in which homologous chromosomes exchange genetic material, confers a protective effect against aneuploidy. These findings confirmed the results of previous aneuploidy studies by McCoy’s group as well as others.4-6

Next, the researchers investigated genetic factors that may be associated with maternal aneuploidy by performing a genome-wide association study. For the analysis, the team controlled for maternal age so they could find genetic variants that contribute to aneuploidy independently from age.

They discovered a significant association between maternal aneuploidy and a variant of a gene called structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 1B (SMC1B), which encodes a protein with a key role in meiotic crossovers. Previous studies indicated that the specific variant the team found results in a lower expression of SMC1B across tissues and that mice lacking the gene had meiotic abnormalities, such as reduced crossovers and chromosome missegregation.7-9

“That was extremely exciting to us because [SMC1B] has been studied for decades in model species because of its role in meiosis,” said McCoy.

In the future, McCoy hopes to identify rarer variants of SMC1B as well as other genes. Such variants are more technically difficult to identify and often selected against in nature. On the other hand, they will likely have a greater impact on maternal aneuploidy. “These might be more meaningful from a screening standpoint,” McCoy said.

Hunt added that investigating the regulation of these gene variants is important too. She said, “We need to understand not only the effect of genetic variants but also how environmentally induced epigenetic changes can affect the developing egg.”

- Hassold T, Hunt P. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2(4):280-291.

- Gruhn JR, Hoffmann ER. Errors of the egg: The establishment and progression of human aneuploidy research in the maternal germline. Annu Rev Genet. 2022;56:369-390.

- Carioscia SA, et al. Common variation in meiosis genes shapes human recombination and aneuploidy. Nature. 2026.

- Hassold T, et al. Failure to recombine is a common feature of human oogenesis. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108(1):16-24.

- Gruhn JR, et al. Chromosome errors in human eggs shape natural fertility over reproductive life span. Science. 2019;365(6460):1466-1469.

- McCoy RC, et al. Evidence of selection against complex mitotic-origin aneuploidy during preimplantation development. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(10):e1005601.

- GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369(6509):1318-1330.

- Revenkova E, et al. Cohesin SMC1 beta is required for meiotic chromosome dynamics, sister chromatid cohesion and DNA recombination. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(6):555-562.

- Murdoch B, et al. Altered cohesin gene dosage affects mammalian meiotic chromosome structure and behavior. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(2):e1003241.