Wind howls and waves roar as storms rage over the open ocean. But even as gusts reach hurricane strength and swells rise as high as six-story buildings, the violent effects of these storms only reach about 500 meters beneath the surface.

“The ocean's four kilometers deep, so there's a whole lot more going on,” said Bethany Kolody, a microbiologist at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley).

Beneath that half kilometer depth, the ocean is quiet. Winds and waves no longer dictate how the water moves; density does. Deep inside the ocean, there is a point at which the water density increases rapidly called the pycnocline. Below this depth, water moves as large layers, termed water masses, based on their densities and sit on top of each other like iced tea and lemonade in an Arnold Palmer. Currents, which are driven by changes in temperature and salinity, circulate these water masses throughout the ocean like slow-moving conveyer belts. In fact, they move water so slowly that some deep water has not seen the surface in more than 1,000 years.

When Kolody was a new graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University for California, San Diego (UCSD), she was focused on studying the ocean at a much smaller scale: its microbes. Ocean microorganisms—from viruses, bacteria, archaea, and fungi to eukaryotic microbes—keep the planet’s oceans healthy by cycling nutrients, converting carbon dioxide to organic compounds, and capturing carbon from the atmosphere.

“I was always interested in these questions about microbial dispersal and [asking], ‘Is everything everywhere or to what extent is everything mixed?’” she said.

As one of her first-year basic science requirements, Kolody took a course on physical oceanography, a field devoted to studying the flow of ocean water, including the physical characteristics that define water masses and how they move.

“Oceanographers will just sort of slice the ocean like a cake, and then you'll see the different water masses, and you can either visualize them in terms of salinity or temperature,” Kolody said. “I was looking at that, and I was like, ‘Wow, can we look at one for microbes?’” But as she posed this question to the expert microbial oceanographers around her, they all said the same thing: No.

“Nobody had really taken a transect and just sliced through the ocean and looked,” she said. Prior efforts to study microbes in the ocean had only looked about 1,000 feet below the surface or had sampled them at specific spots such as around hydrothermal vents or deep inside the Mariana Trench.1

University of California, Irvine marine microbiologist Adam Martiny concurred. “There've been big expeditions like Tara [Oceans] and before that, the Global Ocean [Sampling] by Craig Venter and so forth,” he said.2 “Even though they were a very large and impressive scope, the sampling was really sparse. It was a sample here and a sample there.” No one had systematically sampled a particular patch of the ocean both widely or deeply enough to see how currents and water masses might affect the microbial composition of the ocean.

But now, 10 years after she initially asked the question, Kolody has her answer. A chance email looking for research volunteers set in motion a journey that would lead to one of the most detailed genetic maps of ocean microbes to date—spanning the entire ocean depth from some of the oldest water near Easter Island to newly forming water around Antarctica.3 Not only did Kolody and her team discover that water masses do serve as ecological niches for the ocean’s microbes, but to their surprise, the deep ocean sparkles with more microbial diversity than they ever imagined possible.

Ocean Sampling Excluded Biology for Years

To explore the mysteries of the sea, oceanographers send out ships to sample water from the surface to the sea floor in different regions of the planet, which are called transects. For instance, the Global Ocean Ship-based Hydrographic Investigations Program (GO-SHIP) samples the same ocean transect about every 10 years to see how the ocean changes over time. The scientists aboard these cruises collect data on ocean temperature, oxygen levels, water age, and the distribution of micro- and macronutrients among other chemical and physical variables, which help researchers create precise models to predict and better understand the health of the world’s oceans.

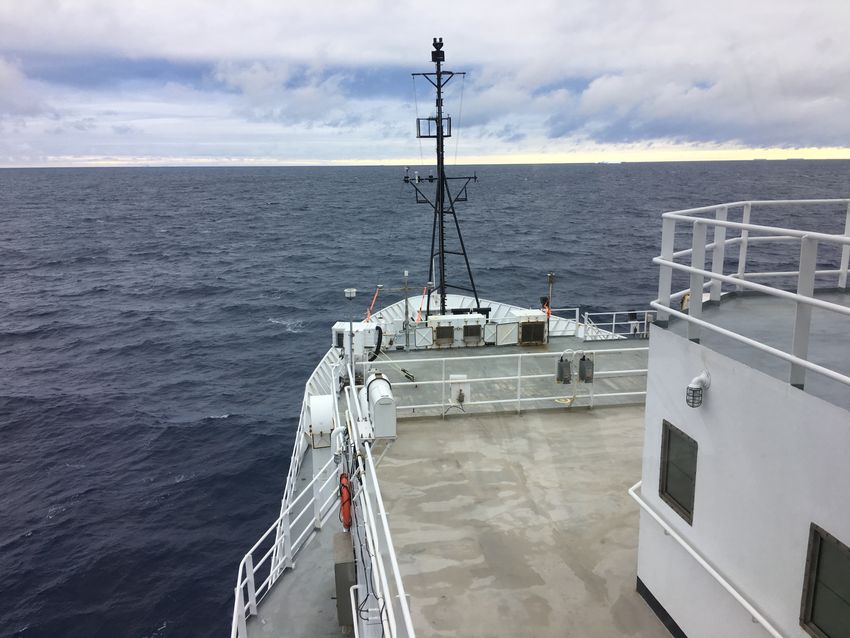

Researchers set sail on the P18 transect of the GO-SHIP program in late January 2017 near Easter Island and sailed South toward Antarctica.

Bethany Kolody

“The physical oceanography community and chemical oceanography community have really done gorgeous ocean atlas—textbook level—work with these ocean sections,” said Andrew Allen, a microbial oceanographer at UCSD and Kolody’s graduate advisor. “This sort of high-resolution ocean observing that the physical and chemical oceanographers have done so well is something we really are lagging behind in in biology.”

Part of the reason for this lag, Allen explained, was that for years, library preparation and high-throughput sequencing methods were not quite advanced enough to analyze that much microbial data economically. Furthermore, scientific cruises like GO-SHIP are themselves expensive to run, making the collected water samples precious resources.

Despite the technological and financial roadblocks, Kolody dreamt of how she would investigate the microbes living in different water masses if she ever got the chance. “You need a really specific transect because you want to capture where the new water is forming, and you want to capture some really old water so that you can say, ‘Are there differences here?’” she explained.

One place where new water forms is around Antarctica. When ocean water freezes into icebergs, the salt gets expelled and dissolves into the water, making the water there very salty. Higher salinity means a higher density, and the addition of the cold Antarctic temperatures makes the water even denser, causing the new water to sink toward the ocean floor. This water movement drives the slow circulation of the water masses throughout the ocean. Further north in the South Pacific, there is a mass of water that is much older. This ancient water is less dense than the new Antarctic water, so it sits less deeply in the ocean. Because of its age, it also contains fewer nutrients than other water masses.

Due to the variations in salinity and available nutrients in old and new water, Kolody hypothesized the different groups of microbes likely lived in these water masses.

“Partway through my PhD, I sort of put it out of my mind. I was like, ‘Oh, that would be so cool,’ but I had other projects,” Kolody said.

But then, an email landed in her inbox that changed everything.

The South Pacific: The Perfect Transect

The email was from GO-SHIP. For their next sampling trip, the team planned to travel along a transect called P18 that spanned from Easter Island in the north to Antarctica in the south, and they were looking for graduate student volunteers to help them process water samples.

“I was like, ‘Wow, that would be the perfect transect to answer my question,’” Kolody said. Knowing it was a long shot, she wrote the researchers back and asked if it would be possible for her to filter some of the water that would be collected to profile the microbes in it. To her surprise, the GO-SHIP team granted her a spot on the cruise and said that she could use any extra water that other researchers didn’t need for her microbial analysis.

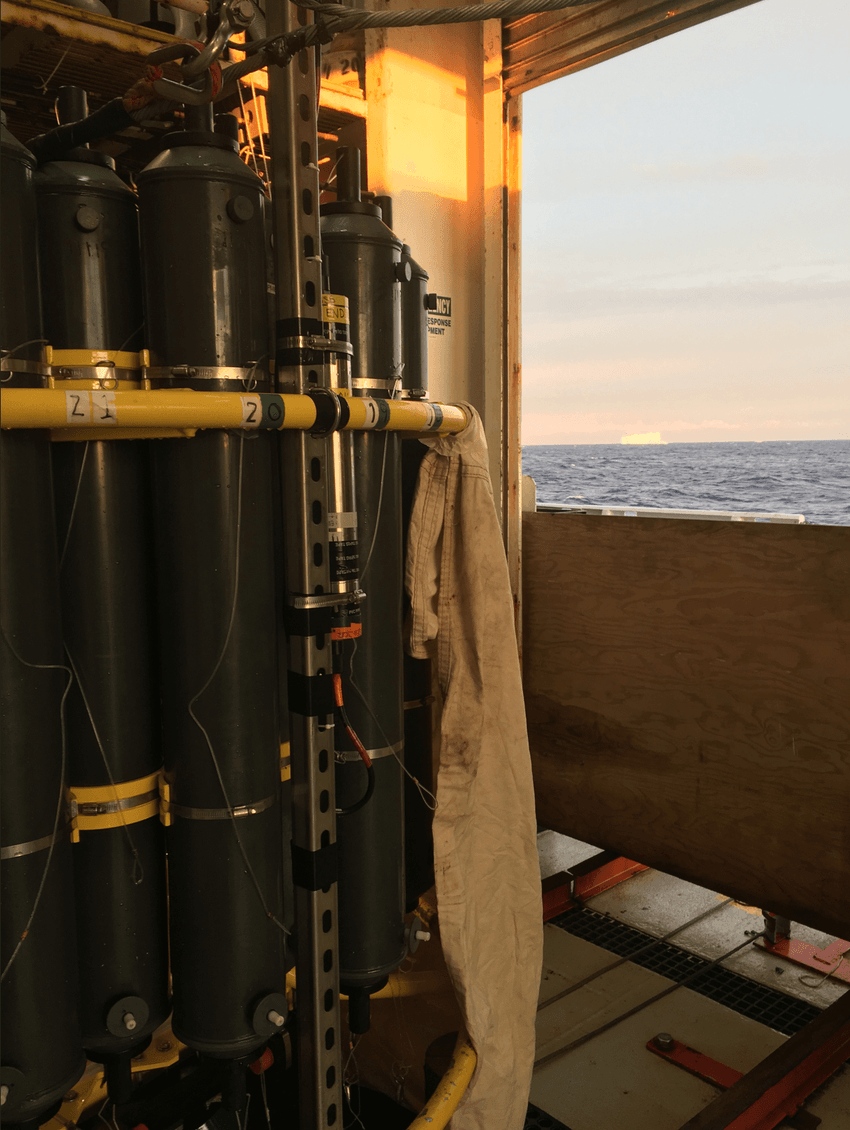

When it was time to take a water sample, the ship’s crew lowered a carousel of open 20-liter water collection bottles and used them to collect water at specific depths for analysis onboard.

Bethany Kolody

“The most incredible thing about this story is how generous and collaborative everybody has been,” Kolody said. “They let a PhD student—with their own idea, with no track record of being able to execute an idea—just come in and shoot their shot.”

When Kolody approached Allen about conducting her project on the GO-SHIP trip, he knew that she could rise to the challenge.

“I'd worked with Bethany for a while by that point, and I knew that if she had set her mind to it, then there's a good chance that she was going to be able to pull it off,” he said. “When your students have the opportunity to really interact with experts in fields that you don't really have expertise in, that's usually where the more interesting breakthroughs can occur, so I was excited.”

Kolody and Allen came up with a plan for how they would analyze the microbial samples she collected; they would look at the species level to identify which microbes were present as well as the genomic level to better understand how these microbes lived and adapted to the unique facets of different water masses. From there, Kolody collected the supplies she would need for what would be about a month-long trip out to sea.

“I didn't have any explicit funding for this project, so I was sort of begging, borrowing, and stealing equipment across Scripps,” she said. “I'd go door to door and be like, ‘Hey, do you need your peristaltic pump from the months of December through January? Do you mind if I take it to Antarctica?’ And people were really awesome about it.”

Soon enough, Kolody found herself flying into Easter Island to join the GO-SHIP team. The whole ship is essentially a mobile laboratory. In one part of the boat, there is an A-frame that holds a multiple-kilometer-long wire that attaches to a carousel of 20-liter bottles that are open on each end. When the researchers want to take water samples at a certain location, they lower the carousel into the water.

Giant spools of cables are needed to reach and sample water from the deepest depths of the ocean.

Bethany Kolody

“You have a computer monitor where you're seeing how deep it is, what the temperature is, what the salinity is, as it's going down,” said Kolody. When the bottles reach the ocean floor or whichever depth the scientists are interested in, they trigger one of the bottles to close from the computer on deck. Moving upward, they continue to close the other bottles at specific depths that they’re interested in. Once the bottles reach the surface again, scientists can take water from the bottles that collected water at particular depths for analysis.

The organizers added Kolody to the water collection schedule when other researchers knew that they would have extra water for her to analyze. As the ship collected samples about every four hours, day and night, Kolody was ready to get her water. She did have to ask the researchers collecting water before her to make one small change to their standard protocol: wear gloves. Because she was the only scientist collecting microbes, she had to prevent any potential microbial contamination from the researchers on the ship—something that the other scientists had never had to consider. Kolody was learning new things too. To collect her microbes, she ran ocean water first through a five micrometer (μm) filter to catch larger eukaryotic microbes like phytoplankton and then through a 0.22μm filter to catch smaller prokaryotes like bacteria and archaea.

“When I arrived at sea and I started filtering, I had only ever filtered for phytoplankton biomass really, and I started filtering these deep-water samples. I was looking at the filter, and it was white like a sheet of paper, and I was like, ‘Did I even get anything? Is there even anything on this filter?’ I only filtered eight liters of water. I just sort of prayed and put it in liquid nitrogen,” she said.

To control for the relative abundance of microbes at different depths and locations, Kolody also saved a small volume of the ocean water to count the number of cells it contained. She continued this process as the ship moved from the ancient water around Easter Island, through other water masses including the upper and lower circumpolar deep water, to the new water in the Antarctic bottom water zone.

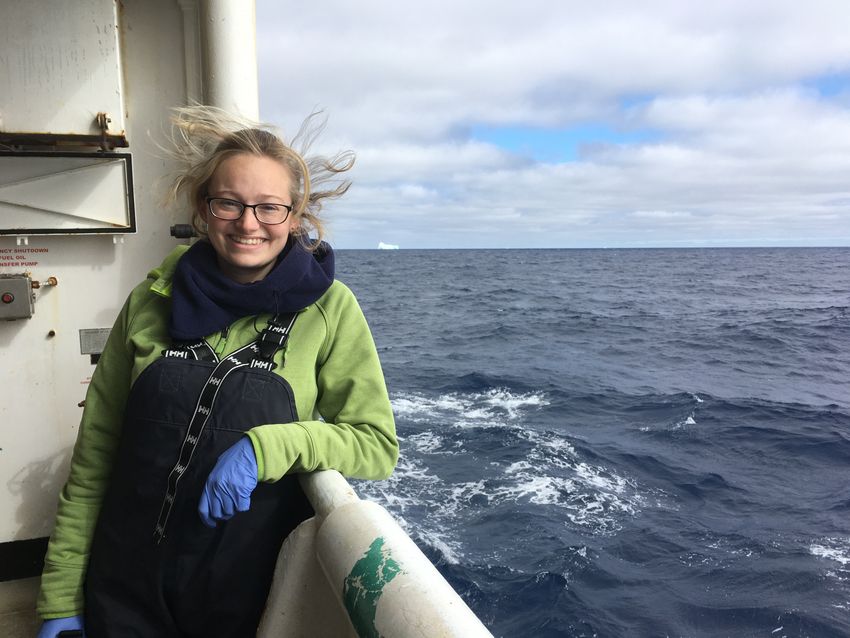

Kolody filtered water along the P18 transect until the ship neared Antarctica and its iceberg-laden waters.

Bethany Kolody

“We were trying to go as far south as we could, until there were too many icebergs, and it got dangerous,” said Kolody. “The crew of the ship that was like, ‘No, we know our limits. This is not going to be a Titanic moment.’”

When the ship landed in Punta Arenas, Chile, Kolody’s boyfriend (now husband) met her there and helped her ship her precious samples back to San Diego where she and her team would finally find out whether ocean water masses shape the lives of the tiny microbes that live there.

A Burst of Microbial Diversity in the Deep Blue Sea

By the end of her trip, Kolody had collected 301 water samples at multiple depths along the entire transect. On these samples, she and her team performed 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) or 18S rRNA amplicon sequencing to identify the microbes within the water masses and metagenomic analysis to get a sense of what the microbes in a given location were capable of.

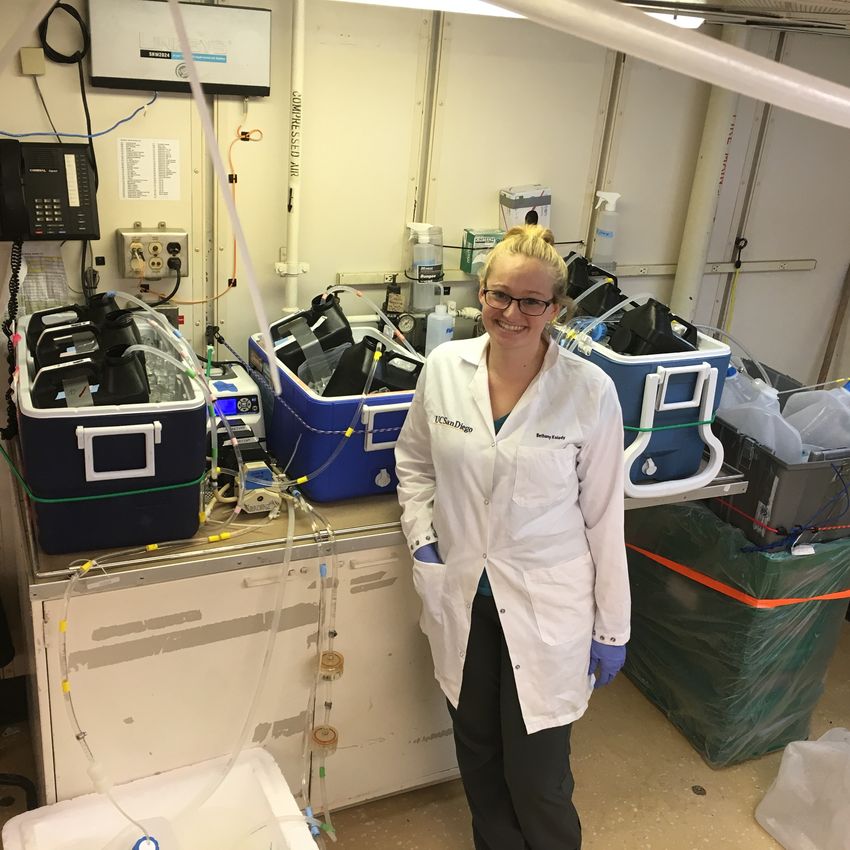

Kolody filters ocean water from a specific location and depth to collect the microbes that are living there.

Bethany Kolody

“To make things even more complicated—because I couldn't leave well enough alone—I really wanted this to be a super quantitative study,” said Kolody. She explained that to get a sense of how abundant a particular microbe actually is in a sample, researchers often add a known quantity of DNA to the sample before sequencing. However, figuring out how much DNA to add to different samples, which could contain many to very few microbes, is difficult. For that, Kolody enlisted the help of Hong Zheng, a research associate in Allen’s group, who he described as having “hands of gold.”

Kolody agreed, adding, “She has so much experience with getting samples from weird environments to work…She was able to finagle these to make them work really nicely, so at that point, I was like, ‘Yes, we have data!’”

By the time Kolody had all of her data ready to analyze, the COVID-19 pandemic had hit, and she had started her postdoctoral research at UC Berkeley with microbiologist Jillian Banfield. While house-sitting for Banfield in Northern California, Kolody analyzed her data. She decided to look at how microbes differed across the span of the ocean. Sitting at her boss’s desk (“which was very inspirational, because she's a genius!” she said), she plotted microbial diversity over ocean depth. At the surface, microbial diversity was low, but as she looked deeper, diversity suddenly exploded.

“I look at that, and I'm like, ‘Oh my God, that's something!’” she said. “That's the pycnocline, but in microbes.”

In fact, at depths beneath the pycnocline, microbial diversity stayed high all the way to the ocean floor. Since the sudden change was in microbial diversity rather than density, Kolody named this depth the phylocline.

“That was the cool thing, because we don't really think about the deep ocean as diverse a lot of the time,” said Kolody. But data from the Tara Oceans study, which sampled the surface and just to about the pycnocline, had also noted lower microbial diversity at the surface and then an incremental increase in diversity at lower depths.1

“It's a little bit counterintuitive,” but Kolody explained that at the surface, microbes will bloom when they find a favorable environment and dominate in that location, leading to less diversity of species there. “There's a lot more mixing in the surface ocean because of atmospheric processes, so that disperses microbes and allows microbes that are really good at thriving in each little environment to get there, [which] is our working theory,” she said.

In addition to depth, Kolody also noted that water age had a strong effect on microbial diversity. In areas near Easter Island where the water was more than 1,000-years-old, there was a dip in diversity. However, in samples from the same location but at deeper depths, where the water is younger, diversity then went back up.

“I think that it has to do with this stagnant, recalcitrant water that has just been really mined for every morsel of deliciousness from the microbes, and all that's left are these really recalcitrant compounds that require some specialization to eat,” she said.

Kolody collects water from one of the 20-liter collection tubes to filter for her microbial analyses.

Bethany Kolody

With the surprising microbial diversity finding, Kolody then asked how these species arranged themselves within the vastness of the ocean. She and her team performed a hierarchical clustering analysis where they took microbial genomes and mapped their abundance over the physical space of the ocean. They saw that the microbes seemed to sort themselves into six different cohorts, and those groups corresponded quite clearly with water masses.

“These cohorts were so crisp. They were so clearly delineated,” said Kolody. “This is an entire ocean basin spatial scale, and a lot of microbial ecology happens on milliliter scales. So, the idea that these microbes are patterned out across latitudes and have a biome across latitudes, the fact that that was so clear, was really surprising.”

The researchers then looked at the functional potential of the microbes’ genomes and found that they mapped into 10 different zones that largely corresponded to the six identified cohorts but also included regions at the surface where the wind drives ocean currents. For instance, microbes living in what the researchers called the “nutrient transition zone,” which includes a wide swath of surface water, had genes for photosynthesis and metabolizing nutrients from phytoplankton, which are useful in a zone with ample nutrients and sun exposure. In contrast, microbes that live in the cold and salty Antarctic bottom water had genes to protect themselves from osmotic stress and genes that keep cell membranes functioning even at low temperatures and high pressure, which are features of such deep water.

“[We also saw] a lot of horizontal gene transfer and transposases in this sinking water around Antarctica, and that was really surprising,” said Kolody. “This water is sinking relatively quickly and is being moved into a more extreme environment. And so, you could imagine that horizontal gene transfer would be adaptive.”

Martiny, who was not associated with Kolody’s work, was impressed with how comprehensive the sampling was. “They were able to really identify these subtle but very significant transitions in microbial communities and functioning across both the surface and also with depth,” he said. “This is a great example of showing that microbial communities are extremely sensitive to the underlying environment.”

MOANA and More Biology on the High Seas

As Kolody wrapped up her data analysis, she was thrilled to have such a detailed data set, but as she looked at plots that mapped temperature or nutrients across oceanic space, she wished she could do something similar for the microbes she collected.

“The problem is there're thousands of microbes, and so it's hard to make a single plot that can distill that sort of information,” and, she added, “[for] these giant, large-scale omics projects, you get six figures in a paper to tell your story, and there's so much more data there that could be mined for years and years…A lot of it could be interesting to people, depending on what they work on.”

As a way to make her microbial genomic data available to others, Kolody dipped her toe into web development and created an interactive tool that she named the Microbial Ocean Atlas for Niche Analysis (MOANA). Using a drop-down menu, users can plot the microbe they’re interested in and see where it is in the South Pacific.

“That's something that I think I want to try and incorporate more going forward in my different omics projects,” she said. “The data is all publicly available, but it's a lot of effort to go through all of the steps to answer a simple question of, like, ‘Where is this microbe?’ And so, this makes it a little bit more accessible.”

The GO-SHIP team returned to Punta Arenas, Chile at the end of their P18 ocean sampling expedition.

Bethany Kolody

Since Kolody collected biological data on her GO-SHIP cruise in 2017, researchers have established a new ocean biology observation program called Bio-GO-SHIP, of which Martiny is one of the founders.4

With Bio-GO-SHIP, Martiny said, “We're nearly done with our first decade of observations of the types that were published in this paper on many different sections.” In the next few years, it will be time for GO-SHIP to sample along P18 again, taking the same measurements and now, looking at the microbes too. “What we really need is these types of papers and these types of observations globally, and we are getting them now,” said Martiny.

With scoops of seawater from the deepest depths, scientists will soon understand more about how these mysterious species help maintain the health of our oceans.

- Sunagawa S, et al. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science. 2015;348: 1261359.

- Venter JC, et al. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 2004;304:66-74.

- Kolody BC, et al. Overturning circulation structures the microbial functional seascape of the South Pacific. Science. 2025;389(6756):176-182.

- Clayton S, et al. Bio-GO-SHIP: The Time Is Right to Establish Global Repeat Sections of Ocean Biology. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022:8.