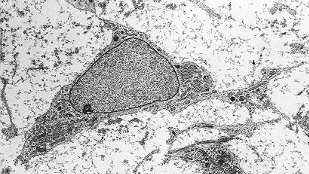

WIKIMEDIA, ROBERT M. HUNTStem cell therapy is often hailed as the treatment of the future for several diseases. And mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)—which can be derived from both embryonic cells and adult cell sources, such as bone marrow, blood, and adipose tissue—have shown particular promise. MSCs are now being tested in more than 350 clinical trials.

WIKIMEDIA, ROBERT M. HUNTStem cell therapy is often hailed as the treatment of the future for several diseases. And mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)—which can be derived from both embryonic cells and adult cell sources, such as bone marrow, blood, and adipose tissue—have shown particular promise. MSCs are now being tested in more than 350 clinical trials.

What makes MSCs special is that they do not express certain cellular markers and thereby manage to evade the immune system. This means they can be administered therapeutically without suppressing the patient’s immune system—a necessity with most grafts and organ transplants. Further, MSCs seem to move toward damaged tissue and assist in repair by both differentiating into key cells themselves, and by recruiting other repair factors to the site. But making MSCs of consistent quality and sufficient quantity to treat patients has been tricky.

A team led by Robert Lanza from Advanced Cell Technology in Marlborough, Massachusetts, this month (March 24) reported in Stem Cells and Development its development of a new line of MSCs derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) via intermediates called ...